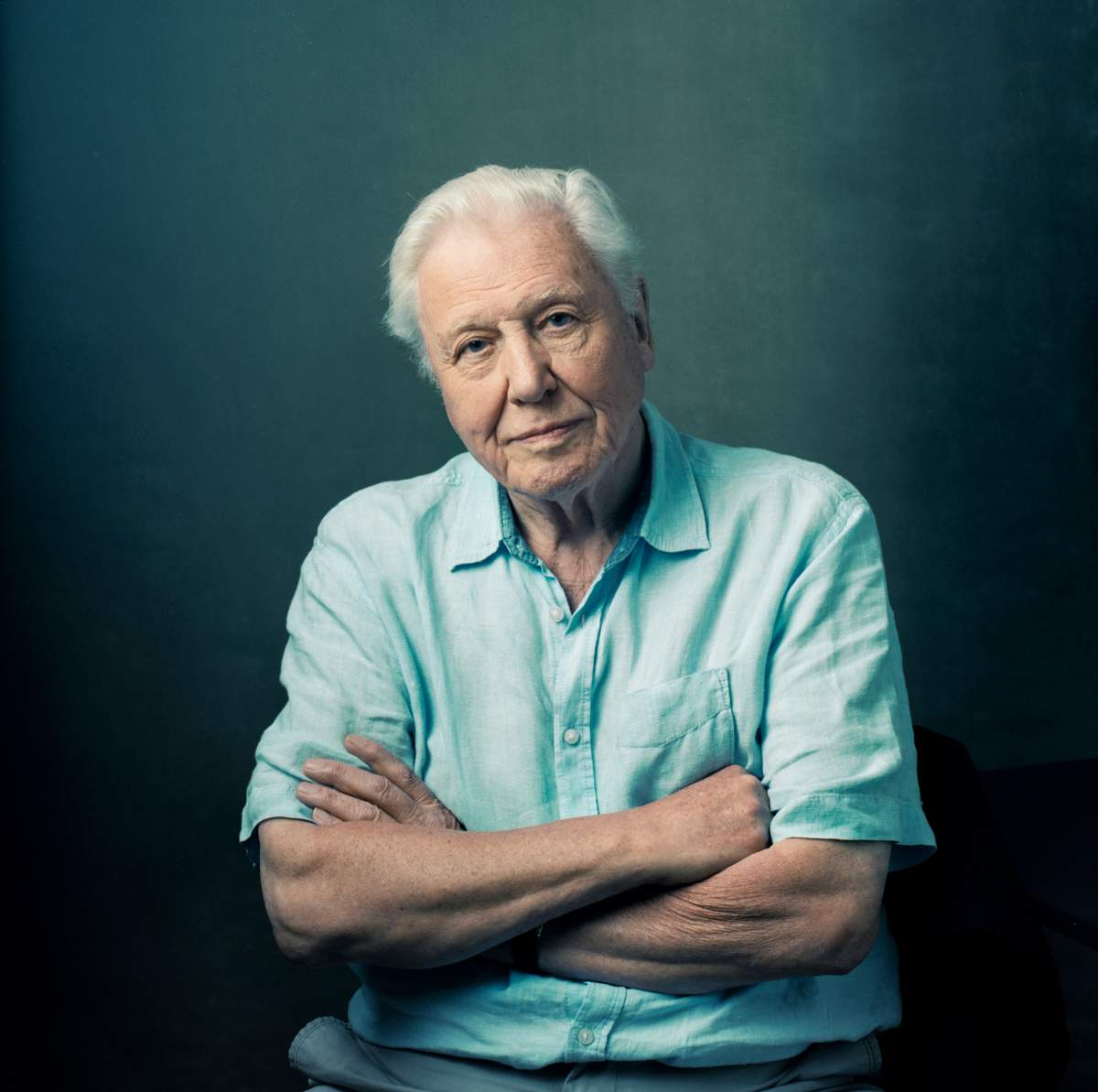

Sir David Attenborough has one of the most recognizable voices in TV history. His calming timbre has been the guiding force of numerous specials, and he’s synonymous with some of Earth’s greatest natural wonders.

Up next: he’s narrating A Perfect Planet, a five-part BBC Earth series offering a unique fusion of natural history and earth science that explains how our living planet operates. The spellbinding series provides a close, at times mesmerizing look at how the forces of nature drive, shape and support Earth’s greatest diversity of wildlife.

The first four episodes explore the power of volcanoes, sunlight, weather and oceans. The final episode in the series looks at the dramatic impact of the world’s newest force of nature — humans — and what can be done to restore our planet’s perfect balance.

Four years in the making, A Perfect Planet was shot across 31 countries (including Canada) on six continents with six volcanic eruptions taking place at featured filming locations. A large chunk of production took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, no less.

- Robert De Niro recites Abraham Lincoln’s warning call for ‘civility’ at Carnegie Hall

- Justin Timberlake sues to block unseen bodycam footage from 2024 DWI arrest

- ‘Evil Dead’ star Bruce Campbell says he has ‘treatable,’ not ‘curable’ cancer

- Creator of Tilly Norwood, AI-generated ‘actor,’ launching the ‘Tillyverse’

Global News was the only Canadian news outlet to speak with Attenborough for his new series, and it turns out the 94-year-old has actually thrived during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Global News: Hi, I’m talking to you from Canada right now.

David Attenborough: Canada, really?

Yes, very international! The first episode of A Perfect Planet is great. We see so many animals, including vampire finches and iguanas nesting in a volcano crater. Do you still get surprised by the new stuff you see after all that you’ve done? These kinds of weird creatures, do they still surprise you?

They do. I’m amazed that we continue to find new stories and new aspects of stories. But the real change is actually how we have been able to perceive those stories.

The flamingo story in the first episode, Volcanoes, is sensational. It has been filmed before, but it’s not been filmed like this because we didn’t have drones. The drones have transformed the impact of the story. To be able to suddenly see this extraordinary salt lake, salt-baked land from above, with these flamingos in the middle, you get to really see what the picture is all about.

I don’t know how long we can go on finding new things to say and new ways to say them. However, throughout my last 60 years, every year, there has been a major ecological, major technical state improvement, which has made us able to see a story in a new way and effectively turn it into a new story.

How was recording the narration during the pandemic? I assume that would have been a bit of a challenge.

We, as you know, are not allowed to travel. Normally, I would have gotten into a car and driven all the way, a hundred miles to Bristol, where there’s a sound studio that we have always used. But I couldn’t do that, so instead, we set up a recording theatre in my dining room.

Get daily National news

In my dining room, we hung duvets all around the walls to knock out all the echoes that you would have heard otherwise. I had a table in front of me with my computer and I was on Zoom — such as we are now — and I had a television set and a microphone with a lead which went through a crack in the window of my dining room into the garden. There, the sound recorder sat on a chair on the lawn, in my garden, listening to everything I was saying. Most recently we got a little hut for him, so he didn’t have to do it in the rain.

Now, meanwhile, down in Bristol, 100 miles away, the producer is sitting watching the monitors and hearing my narration. He tells me when I pronounce the words wrong or if I’m not doing it in the right sort of way. We were able to record the entire commentary and we were concerned whether, in fact, it was going to sound like an amateur setup, but the result was indistinguishable from people listening with very sharp ears, indistinguishable from doing it in the way the professionals were doing it with the recording theatre, so we’ve been doing it ever since.

Have you been staying home since the pandemic was first announced in March?

Oh, yes. Last March I was confined to my house and because I’m very old, I’m in the most vulnerable category. I was told not to go out and not to talk to anybody. My daughter, happily, very nobly, lives in the same house here and she came into lockdown with me. She looks after the running of the house and produces all the meals, which is wonderful. I have not left the house except to go to have my teeth checked at the dentist.

I don’t know if you realized, but Blue Planet began just after September 11th. In the current environment, again, when the world is scared, a lot of people have turned to nature as a calming force. Do you think people will be more appreciative and put greater value on the calming, soothing value of nature and the world around them?

I think it has been proved clinically, actually. I think medically and psychiatrically it has been demonstrated that people, particularly people having a bad time, find a lot of support in nature, which they didn’t realize they owed so much to. Psychiatrists are showing an awareness of the natural world is a crucial element in our human personalities and without it, we get sick, psychologically sick.

If you could give one piece of advice to readers on how to get out of the climate crisis we’re in right now, what would you say?

One of the solutions we should be solving is the problem of large-scale storage of power and transmission systems which can transport power over long distances without major loss.

We know the principles involved, we know the technical answers to those problems, the practical engineering problems have not been solved, but once it is, once Morocco can supply the whole of southern Europe with energy, problems about solutions of power will disappear. It will also bring wealth to nations outside Europe, for example.

You’re considered the world’s most well-travelled naturalist. I would be curious to know what animals and/or creatures you enjoyed documenting the most?

I suppose, filming primates is a very rewarding thing to do. They are so beguiling. They are so intelligent. They are so like us. I look back and those occasions when I’ve sat with gorillas or chimps are very special. They are so like us it’s extraordinary. I suppose I should say the same thing about octopus, which, after all, are extremely intelligent and don’t have the material culture that we do, but nonetheless are very, very bright. That’s a different world altogether, but the world of primates is so easy to identify, so easy to understand, so easy to see the problems, and so tragically easy to see what we have been doing to them.

Is there something you still want to capture on film in your lifetime, something that you haven’t had the opportunity to do yet?

Oh, yes, lots of things. There is no practical reason in which I’m actually going to dive with the great giant squid, for example — my days of giant squid diving are over, I may say, and that never happened.

I just had an extraordinarily lucky time. I can’t imagine when I set out and when I was a young man, I couldn’t imagine that I would be able to go anywhere in the world and see pretty well everything I ever wanted to.

Do you still have an appetite for travel? Do you think you’ll still film overseas if you’re asked to?

No, not a lot. I can tell you it’s probably a factor of age, but I was finding my heart sinking deeper and deeper into my boots every time I walked up into an aircraft and looked down that long line thinking I’m gonna be here for another 24 hours. It didn’t make my heart lift with pleasure.

How have you passed the time both professionally and recreationally since the pandemic started?

Oh, I’ve got a million things to do. I still haven’t sorted out sections of my library that have got themselves in a frightful muddle. I’ve got lots of geological specimens I’ve collected over the years that have been sitting in my cellars for a long time without proper documentation. I promised myself I would put that right.

I’m just very busy and presently so. I feel a bit uneasy saying these things because I know for a lot of people, this has been a real sacrifice, a real trial and not being able to see your loved ones and your relatives is a great trial. And if you haven’t got a garden, it must be really terrible. Living by yourself must be very hard indeed. I don’t want to minimize that. All I’m saying is, for me personally, I have not suffered very much during these last nine months.

With shops delivering to your doorstep when you order by telephone… I’m in contact with people professionally on Zoom, I work quite hard. I write commentaries; they’re keeping me busy. I get between 50 and 70 letters a day from viewers and I can tell you, it takes a long time to answer them. I’ve not been idle.

—

The Canadian broadcast premiere of ‘A Perfect Planet’ airs January 3, 2021 at 8 p.m. ET/PT, exclusively on BBC Earth in Canada.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.