Seventy-five years after a Canadian flight officer was killed in action in the Second World War, his cross-marked tombstone will be changed to reflect his Jewish faith.

The story of the late Morley Ornstein’s new Star of David involves determination and collaboration by a Canadian journalist, a British researcher and historian, and a 92-year-old childhood friend of Ornstein himself.

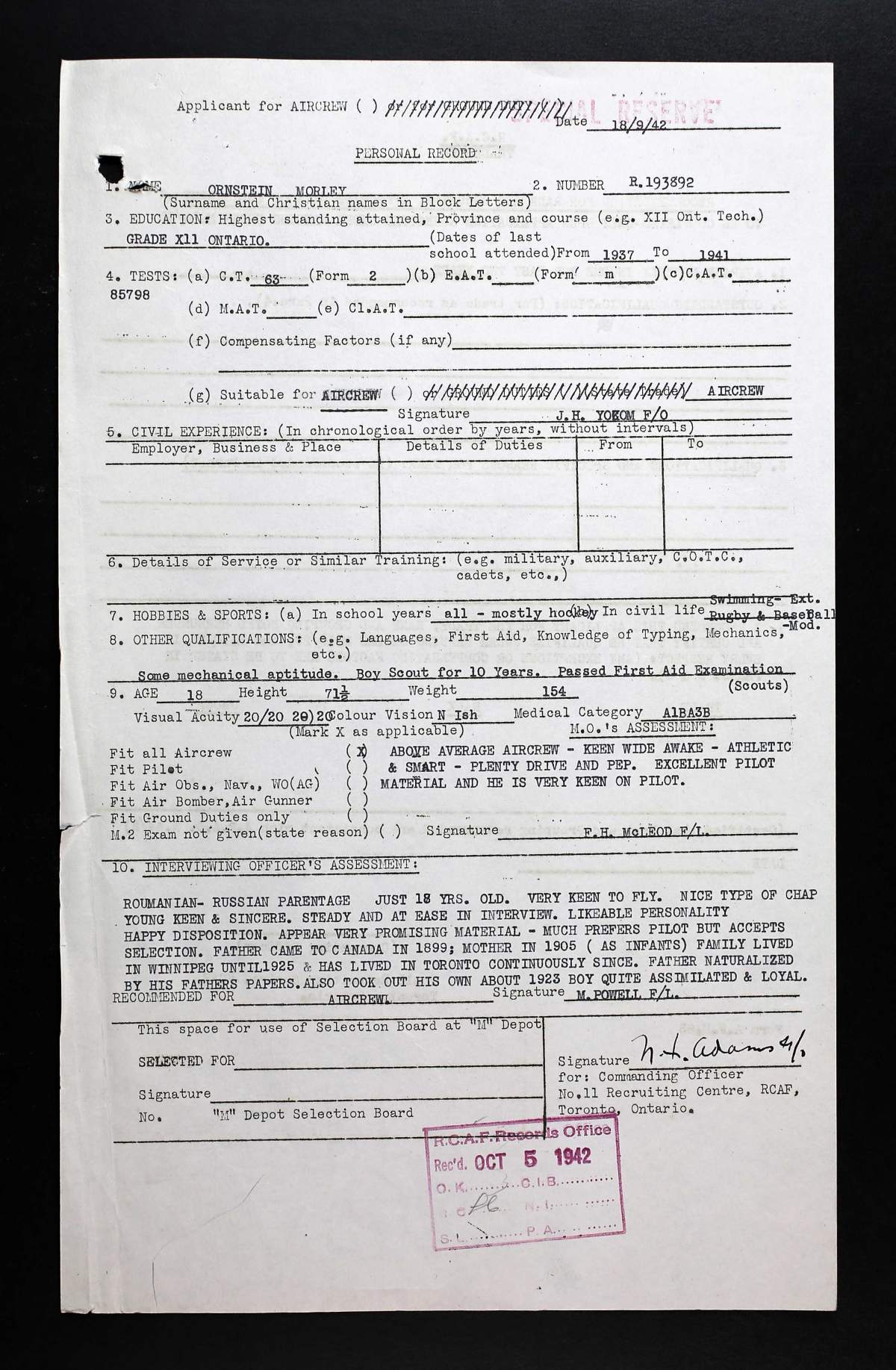

Ornstein grew up in Toronto and enlisted in 1942 right after his birthday. His interviewing officer noted in his military assessment: “Just 18 yrs. old. Very keen to fly. Nice type of chap. Young keen & sincere.”

Flying Officer Ornstein served as a navigator on a Lancaster bomber crew based in England. In March 1945, just a couple of months before V-E Day marked the end of the war in Europe, the crew was heading back from a daytime raid over Bremen, Germany when the Lancaster was hit by flak.

While the details aren’t all known, Ornstein is believed to have successfully bailed out of the crashing plane, but he and his parachute became caught in a tree on the way down. His family believed he was then shot dead while he was stuck, based on testimony later given by locals to investigators.

Unable to reach his family to confirm burial requests after the war, officials marked Ornstein’s grave with a default cross.

Seventy-five years later, a photo of that headstone was spotted by journalist and author Ellin Bessner. She wrote ‘Double Threat,’ detailing stories of the 17,000 Canadian Jews who served in the Second World War.

“I’m a mom of boys who are that age, and Morley died and sacrificed themselves so that my kids could go to university, my kids could finish high school and my kids could have a life here and freedom in Canada. And it was the least I could do to fix it,” Bessner said.

Nine of Bessner’s own family members served in the same war. She says when most people think of Jews and the Second World War, they think of the six million victims of the Holocaust.

“They don’t think that Jews were also the liberators, the victors who helped stop the Second World War and end the Holocaust. And having Morley’s grave with the correct religious symbol shows that he went there to save Canada, the world, and his own people, from the Final Solution.”

Bessner had never petitioned to have a stone changed before, so she reached out to someone who has done it successfully more than a hundred times all over the world.

Get daily National news

Martin Sugarman is a British researcher and historian who serves as the archivist for AJEX, the Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women of the UK.

He calls his unpaid, volunteer quest to have incorrectly-labelled headstones inscribed with Jewish stars a “life’s work.”

“These are not deliberate mistakes, they’re through the fog of war, or not finding the families and getting their permission and what they wanted inscribed on their son or their husband’s grave,” Sugarman explains.

“And when we can prove that they were Jews, I submit all the documentation.”

He says the changes are very important in the fight against anti-Semitism, and to help push back against the false idea that Jews didn’t serve in that war.

“We’re raising the level of our sacrifice by having more graves with these Stars of David on them,” said Sugarman.

Bessner researched and gathered Ornstein’s relevant records, including several where he marked his religion as “Hebrew.”

Their case got a boost from another Morley.

The Ornsteins lived on Euclid Avenue in Toronto, in what was at the time a very Jewish neighbourhood. And just down the very same street lived their friends, the Wolfes. Morley Wolfe was four years younger than Morley Ornstein.

Both attended Harbord Collegiate Institute which is bordered by Euclid, where today a monument to the dozens of fallen students who served in the Second World War includes Ornstein’s name.

Now 92 years old, Wolfe still has vivid memories of the whole Ornstein family: carpet salesman father Ben, sweet and quiet-spoken mother Esther, older brother Robert who also served as an airman, and Morley.

Morley “had a lovely sense of humour” and was intelligent, remembers Wolfe. He remembers rides in the Ornstein family car, and the smell of Ben Ornstein’s cigar.

And critical to proving Ornstein’s Jewish identity: Wolfe remembers all the parents speaking Yiddish, a language of European Jews.

So Wolfe wrote a letter to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), joining the call to have his old friend’s grave updated.

“I am well-acquainted with Yiddish, having graduated I.L. Peretz Jewish School in that language. Both my parents spoke Yiddish, and I certainly have a clear recollection of Morley’s parents conversing with mine, on occasion, in Yiddish, obviously indicative of Morley’s background,” read Wolfe’s letter.

And the trio’s efforts worked.

“The different pieces of the puzzle that come together to mean that we can be confident that he identified as a Jew and therefore, that is the most appropriate religious emblem to be going onto his headstone,” CWGC Commemoration Officer Catherine Nell told Global News.

The CWGC has commissioned a new gravestone with a Star of David. COVID-19 restrictions in Europe are blocking its transfer to the war cemetery in Becklingen, Germany, but the organization promises it will be installed as soon as allowed.

The CWGC is responsible for 1.7 million Allied war graves and memorials around the world. After the First and Second World War, the CWGC contacted hundreds of thousands of families to inquire about burial wishes. They weren’t successful in all cases, including Ornstein’s.

“Because we didn’t have that contact with the next of kin we were able to open that investigation. So wherever possible, we honor the next of kin at the time that choices were made. However, in Morley’s case, that wasn’t the situation,” Nell said.

Now, more than a hundred years since the First World War, Nell estimates they still approve about half a dozen religious emblem changes a year.

Sugarman has had some requests turned down, without enough evidence. He says sometimes it takes six months to get approval. Ornstein’s took just eight weeks.

“I think it was so clear,” Sugarman says of the evidence in this case.

But there are still parts of Ornstein’s story that remain a mystery: in addition to exactly how he died, there are also questions about whether it is in fact his body in the grave.

“They didn’t have the DNA techniques we have today,” said Bessner about the efforts to rebury people in military graves after the war. Ornstein was reburied in the Becklingen War Cemetery in 1946.

“They did their best. And they put people in graves. And we’re not sure if he was the same person as Morley Ornstein because the height is different, the hair colouring is different … I just know that’s the only place in the world, in a war area, where people can go and pay respects to Morley Ornstein.”

There’s also the question of what happened to Ornstein’s family. While his military file includes letters written by his mother to the government trying to find out about the fate of her son after the crash, the Commission was never able to reach Esther Ornstein about the grave.

Those involved in Morley Ornstein’s story today hope by raising awareness, a relative may come forward.

And every successful headstone change has Sugarman reflecting on his own large Jewish family’s military history and sacrifice.

Wolfe says he’s very pleased with the outcome, and he called it a “serendipitous pleasure” to be able to help.

“When you want to remember somebody, you want to remember them as they were, not as somebody else decided who they were going to be,” he said.

Comments