By now, the measures to protect ourselves during the coronavirus pandemic are engrained in our minds.

But with “pandemic fatigue” an increasing concern, public health experts are reminding people of the importance of these measures using an unusual metaphor — cheese.

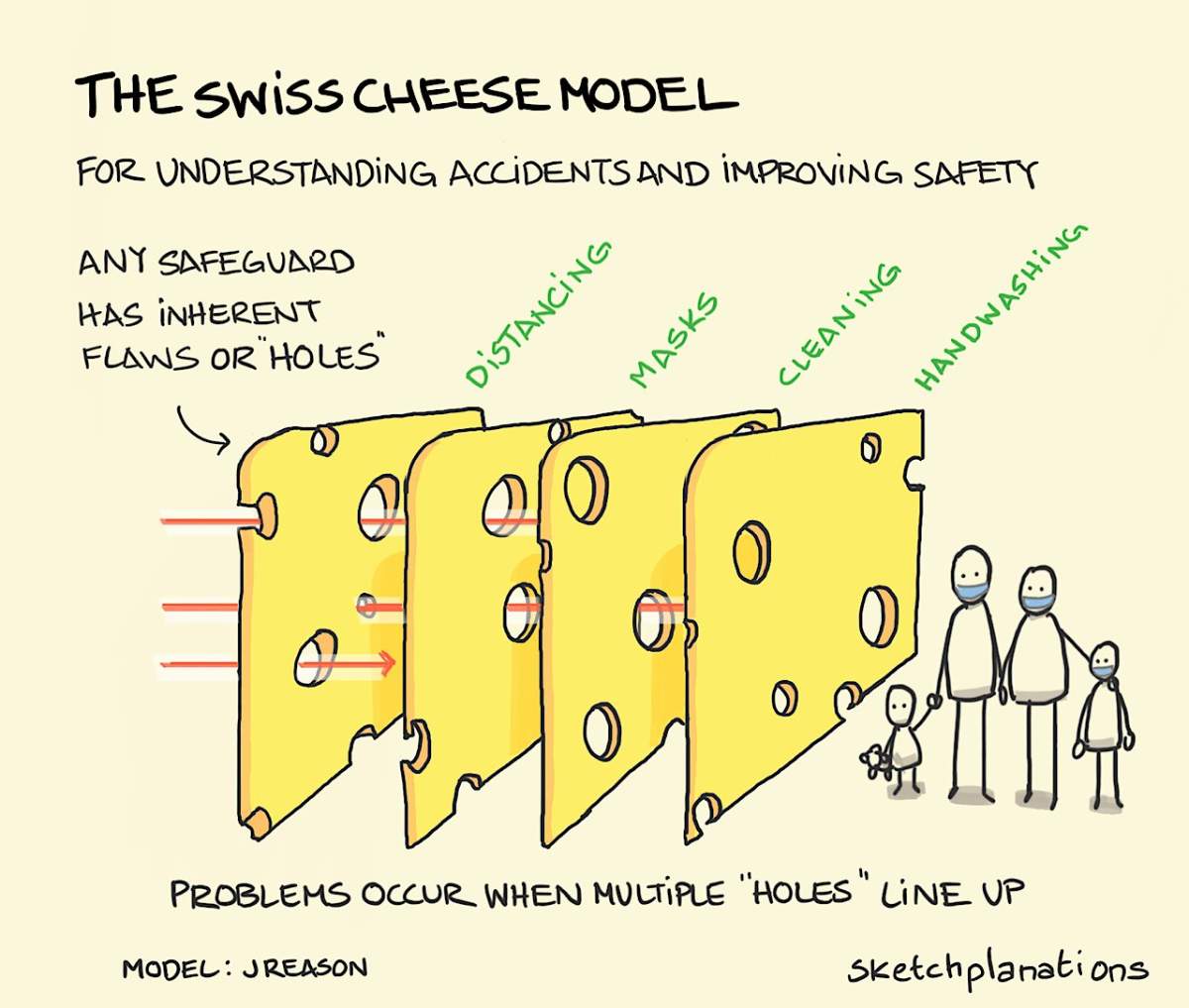

The “Swiss Cheese Model” uses slices of cheese to visualize how interventions work together. Each intervention — including physical distancing, mask-wearing, hand washing and disinfecting — is depicted as an imperfect barrier to virus transmission by the holes in the cheese.

When multiple effective, but imperfect, interventions are combined like a stack of Swiss cheese slices, some of the holes in the cheese are covered and virus transmission is decreased or even stopped. Some viruses might get through a couple of holes, but the odds are low that holes in every slice would line up and allow the virus to slip through the entire stack.

“The beauty of this is that it shows every one of these interventions has strengths and weaknesses,” said Colin Furness, an infection control epidemiologist and assistant professor at the University of Toronto.

“It shows why you want multiple interventions. You want to pile them together.”

How it works

The model itself is nothing new.

It was created in 1990 by James Reason, a professor at Manchester University, who wanted to shed light on human error and how mishaps could be prevented by “a series of barriers.” It’s now used extensively in health care, risk management, aviation and engineering.

Get breaking National news

Each layer of defence is broken down but linked together, showing that intervention at any stage could help stop a problem from unfolding.

The theory shows “how errors line up to cause big, catastrophic outcomes when there’s a series of small mishaps that occur in a sequence,” said Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease specialist based out of Toronto General Hospital.

We already apply it in other aspects of life, he said. Take driving, for example.

Speed limits control how fast we drive, intersections are engineered for safety, seatbelts can help restrain us in a crash and airbags can help minimize injuries. None of these protections are perfect individually, but when combined, they help reduce the risks of driving.

“It’s a way to appreciate bundled approaches to risk mitigation,” Bogoch said.

“So if people aren’t wearing masks and aren’t distancing and aren’t practising good hand hygiene, if all of these start to align, then the risk of acquiring COVID-19 goes up.”

COVID model

The coronavirus version of the Swiss Cheese Model was adapted by Ian M. Mackay, a virologist in Australia. It made its way to Twitter this week, where public health experts from around the world hailed it as an effective way to visualize how an individual can help combat the spread of COVID-19.

Mackay’s iteration included seven cheese slices as interventions or barriers: physical distancing, ventilation, masks, hand hygiene, fast testing, contact tracing, and surface cleaning.

It’s the combination of “contact reduction” interventions, like limiting gatherings, and “transmission reduction,” like masking, that makes this work, according to Nicholas Christakis, a physician and sociologist at Yale University.

“No matter the specific combination of non-pharmaceutical interventions, so long as a certain threshold is achieved, the pandemic can be brought to heel,” he tweeted on Oct. 11.

“One just needs enough layers of Swiss cheese, but not necessarily all of them.”

In other words, Furness said, it comes down to the circumstances of transmission, which the model might not completely depict.

It’s not perfect, he added.

“Every one of those arrows in those diagrams needs a narrative. Here’s the vector, here’s how illness gets from one person to another, and here is how distancing, cleaning, and handwashing either do or do not prevent that,” he said.

“What are the situations that evade this?”

Individual risks

Mackay said that it’s not necessary to get hung up on the order each protection or cheese slice is placed.

“It’s about the whole rather than any one slice,” he tweeted.

The model also isn’t made to be reversed, Bogoch said. “At the end of the day, this is a way to conceptualize protections at an individual level.”

He said these protections will all play a role in risk reduction for the foreseeable future, likely even after a vaccine is developed and distributed.

The point of the model is to see these interventions as “complementary, not substitutable,” Furness said.

“Ventilation and masks are not the same. They come at the problem in a different way,” he said. “It’s not a bargain. You can’t say, ‘I’m not doing that, therefore I don’t need to wear a mask.'”

Now that Canada and much of the world has passed a lockdown stage, there are more scenarios where a person can apply this model, he continued.

He said Canadians can look at the model and simply ask themselves if the scenario they’re about to take part in is safe.

“In this sense, indoor dining would be clearly inappropriate. You’re relying on the restaurant to do cleaning, you can do handwashing, distancing and masks are out the window, so that’s bad,” he said.

“It gives you a sense of what risks are involved in a particular situation, and what slices of cheese fall off.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.