A Canadian whose widely-publicized account of conducting executions for ISIS fueled public outrage and debate in the House of Commons has been charged with allegedly making it up.

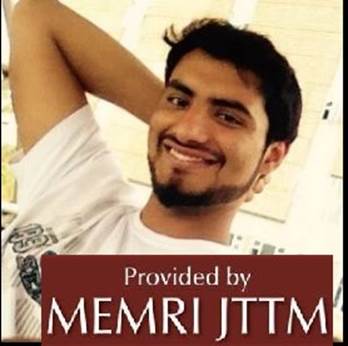

Shehroze Chaudhry, 25, who has portrayed himself as a former ISIS member living freely in Canada, was charged with faking his involvement in the terrorist group.

The Burlington, Ont. resident is to appear in court on Nov. 16 to face a terrorism hoax charge. Reached at work, he declined to comment.

The son of an Oakville shawarma and kabob shop owner, Chaudhry has been posting on social media and telling reporters and others since 2016 that he was a former member of the ISIS religious police in Syria.

Two sources who know him said that, under the alias Abu Huzayfah, he was the subject of the award-winning New York Times podcast Caliphate, where he described conducting public executions.

His Facebook page profile has also described him as “Abu Huzayfa” and a “mujahid” or jihadist.

RCMP spokeswoman Sgt. Lucie Lapointe also confirmed in an email sent to Global News on Friday evening that Chaudhry was the Abu Huzayfah featured in the New York Times podcast.

The charge “stems from numerous media interviews” that were “published in multiple media outlets, aired on podcasts and featured on a television documentary, raising public safety concerns amongst Canadians,” the RCMP said in a statement.

Instead, an investigation by the RCMP’s Toronto Integrated National Security Enforcement Team resulted in a rarely-used terrorism hoax charge.

“Hoaxes can generate fear within our communities and create the illusion there is a potential threat to Canadians, while we have determined otherwise,” said stated Superintendent Christopher deGale, who heads the Toronto INSET.

“As a result, the RCMP takes these allegations very seriously, particularly when individuals, by their actions, cause the police to enter into investigations in which human and financial resources are invested and diverted from other ongoing priorities.”

Canada’s terrorism hoax law is sometimes used to prosecute those who make false bomb threats, and is based on the premise that even bogus claims of terrorism spread fear and consume police resources.

Applying it against someone who allegedly fabricated his involvement in a terrorist group “is not something that we’ve seen before,” said University of Calgary law professor Michael Nesbitt.

The maximum sentence is five years.

Concerns that an outspoken ISIS killer was living in the Toronto area set off heated exchanges in Question Period, with the Conservative opposition calling for his arrest and asking the Liberal government why it wasn’t “doing something about this despicable animal trekking around the country.”

“The blood was just — it was warm, and it sprayed everywhere,” Abu Huzayfah said in the Caliphate podcast, recalling killing a drug dealer. “And the guy cried — was crying and screaming.”

“It’s hard. I had to stab him multiple times. And then we put him up on a cross. And I had to leave the dagger in his heart.”

Get daily National news

But his story has not been consistent. While he wrote on Instagram that he had been in ISIS “for a bit less than a year,” he told Global News he was in Syria less than six months.

His account of having joined ISIS in January 2014 was also contradicted by his academic transcript, obtained by Global News. It indicated he was a student at the University of Lahore’s Department of Environmental Science in Pakistan throughout 2014.

In addition, he denied to Global News having ever killed anyone, but in an interview aired on the podcast, provided vivid details of executions he said he had carried out.

On Twitter, the Times reporter behind the Caliphate podcast, Rukmini Callimachi, defended her work, explaining that “multiple” U.S. intelligent agents had told the newspaper that Chaudhry had gone to Syria.

She said the newspaper had “geolocated an image of him shooting a pistol over a river in Syria. But we also know he didn’t travel on his own passport.”

Since Canada will not send investigators to Syria, “how do they hope to build a case against a member of ISIS?”

Amarnath Amarasingam, a Queen’s University professor who has been speaking with Chaudhry since 2017, was surprised by the RCMP allegations.

“While there were always questions about when he went to Syria, nothing in my interactions with him suggested he made the whole thing up,” he said.

“It will be a very hard case to make though. They have to prove that others thought terrorist activity would occur and fear death/harm, that he intended to create that fear, and that he knows the info is false.”

“That’s a tough climb I think.”

Chaudhry graduated from Lester B. Pearson High School in Burlington in 2012, according to his social media pages. He began studies in Lahore in 2013, according to his academic record.

He earned an A in English in his first term, and an F in Islamic Studies, it said. In his final term in the winter of 2016, he received all Fs.

After returning to Toronto in 2016, he began posting online about where he had been during his absence from Canada: Syria.

On Nov. 3, 2016, a post on his Instagram account denounced the former ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, as a “fake,” prompting another user to call Chaudhry a “clown,” according to an image of the exchange in a report by the Middle East Media Research Institute.

Chaudhry responded that he was an ex-ISIS member who had been “stationed in Manbij, Raqqa, and Rabia. … I’ve been on the battlefield, I’ve done my part,” he allegedly wrote on Instagram.

The exchange caught the attention of MEMRI in Washington, D.C., which published a report for its subscribers entitled: “On Instagram, Ontario Man Alleges That He Fought With ISIS in Syria.”

MEMRI said it had also found posts on his Facebook page, which have since been deleted, praising the late Al Qaeda propagandist Anwar al-Awlaki, calling him “the best imam of all time.”

Additional online posts found by MEMRI showed armed fighters and weapons. “Other guy goals,” read the caption of a Facebook photo of shoes. Below it was a photo of firearms and the caption, “My goals.”

“Chaudhry is also active on Facebook and occasionally posts anti-Assad items on his page, along with anti-Israel items,” MEMRI wrote. “His Facebook activity also reveals an enthusiasm for combat and weaponry.”

Since returning to Canada in 2016, Chaudhry has been working at his family’s restaurant and studying at York University, according to his LinkedIn page.

In August 2017, he told Global News he had used his Pakistani passport to travel to Syria, so there was no trace of the trip in his Canadian passport. He said he had grown disillusioned with ISIS and escaped to Turkey on a motorcycle. He then returned to Pakistan, and from there to Canada, he said.

“All that’s behind me,” he said, speaking on the condition he would not be publicly identified.

For the past year, according to his LinkedIn profile, he has been interning at Parallel Networks, a U.S.-based company that harnesses reformed violent extremists to combat hate and extremism.

Only a “handful” of terrorist hoax charges have been prosecuted to date, said Nesbitt, a leading expert in Canadian national security law.

“It’s usually with respect to an individual who is calling in a threat about something or posting something online,” he said.

The prosecution will have to prove there was a hoax, that it was done with the intent to cause fear, and that it was “likely to cause a reasonable apprehension that terrorist activity is occurring or will occur.”

Nesbitt said the Crown may intend to argue that, because the hoax was so widespread and was featured on a popular podcast, it created fear that Canadian ISIS members were “returning and running around,” and that police were powerless to stop them.

“We can imagine that might be where they’re going,” he said.

For his part, Chaudhry could find himself in the awkward position of arguing that it was not a hoax and that he was indeed a former ISIS member.

The most common terrorism hoaxes are letters containing powders, often said to be anthrax, that are sent to targets, according to a 2016 academic paper on the topic by Nicole Tishler of Carleton University.

Bomb hoaxes are the second most frequent, the paper said. Although they are by definition false alarms, hoaxes can be a tactic designed to manufacture terror and send police on goose chases.

“At the most superficial level, terrorism hoaxes are those incidents that are believed to be acts of serious terrorism, but do not actually involve any real risk of harm,” Tisher wrote in “Taking Hoaxes Seriously.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.