Over the past few months, everyday housework, like cooking and washing dishes, has multiplied and most parents have become responsible for teaching their kids. Given the uneven distribution of these tasks before the pandemic, much of this extra work has fallen squarely on mothers.

Our work looks at trends in housework and child care during the early stages of the pandemic in Canada as one way to measure how it might disproportionately harm women.

READ MORE: Coronavirus pandemic sees surge in online shopping, with sales up by 99%

Housework and child care are important markers of equity for a few reasons. Family responsibilities often default to mothers, negatively impacting their career and economic opportunities. Women’s physical and mental health is linked to how equally partners share family-related tasks. Romantic relationship quality and stability are also tied to perceptions of equity in housework and child care.

(Picsea/Unsplash)

Housework and child care

We surveyed nearly 1,250 Canadian mothers and fathers about family and work arrangements before and during the pandemic. Because of the substantial gender gaps in housework and child care before COVID-19, we looked at the perception of how much domestic work Canadian fathers were doing immediately before the pandemic in May 2020, about a month and a half after public health orders took effect.

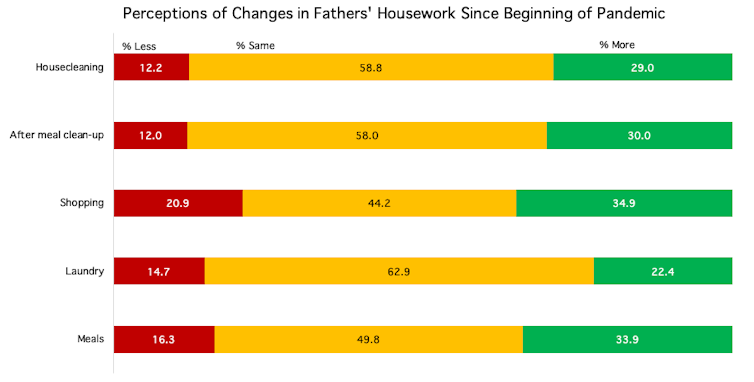

When it came to preparing meals, cleaning and shopping for essentials, a small proportion of men were perceived as reducing their portion, most did about the same and a sizeable minority increased their share. Indeed, in the central tasks of preparing meals, doing dishes and housecleaning, about twice as many men increased their share as decreased it.

READ MORE: Academics discuss challenges of full-time work and parenting amid COVID-19 pandemic

Notably, shifts are uneven across tasks. For example, fathers took on less of the laundry — the task fathers did the least before the pandemic — than meal preparation or going to the grocery store. Although many men do the majority of tasks like lawn mowing or house repair, these are fundamentally different activities because they are done less frequently and are often non-essential.

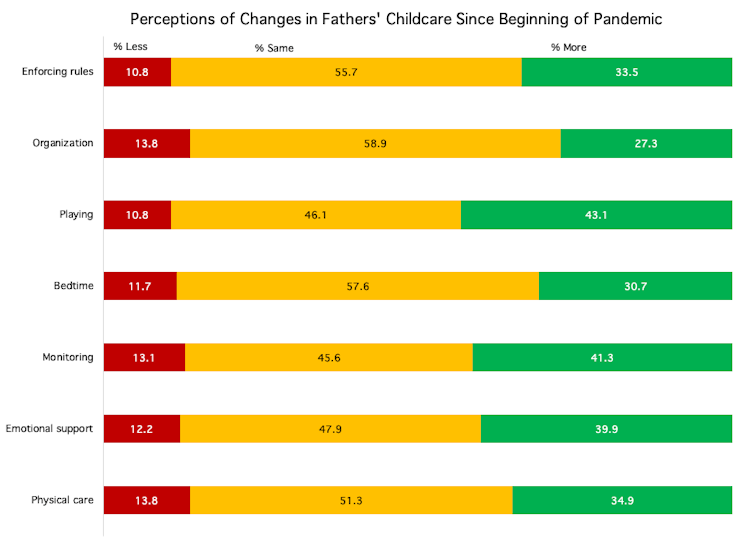

In considering child care, we looked at a gamut of parenting tasks: from enforcing rules to organizing daily routines and activities. The patterns around child care largely mirror those for housework. Interestingly, increases in paternal task sharing are highest for those tasks most commonly associated with fathering — like playing with children.

Get breaking National news

At the same time, however, a number of fathers are increasingly engaged in physical caregiving (e.g., changing diapers, helping kids get dressed, etc.) and providing emotional support. In an era where kids’ routines have been suddenly upended and their mental health has appreciably declined, this may be an important shift in the paternal role.

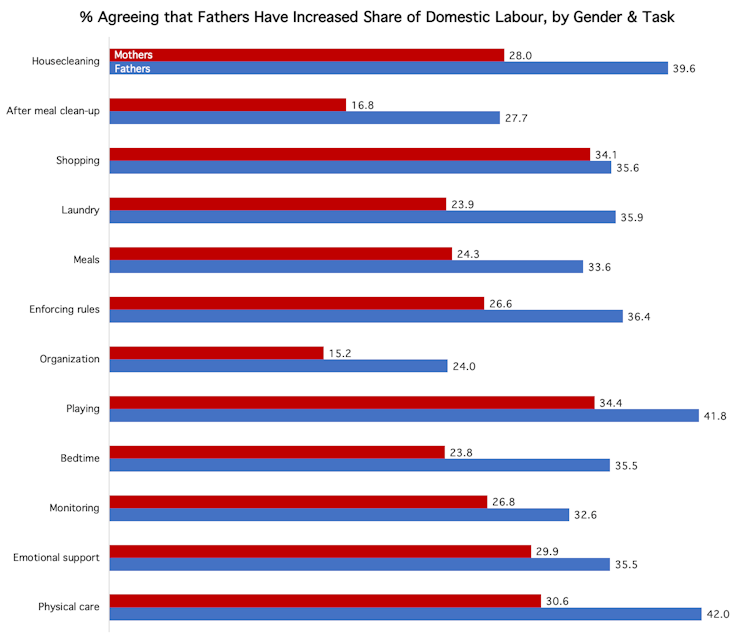

Of course, mothers’ work in the home increased, as well. But notably, we found that both mothers and fathers report a movement toward more equality in most tasks — although there are important gender differences in these perceptions.

Stagnation or regression

There is good reason to worry about the effects of COVID-19 on gender equality. Although the percentage of women in the paid labour force has doubled in the past 50 years, men’s participation in domestic labour has failed to keep pace. In 1986, Canadian fathers spent about 40 per cent of the time mothers put into housework and child care. Three decades later, those gaps have narrowed, but women still perform the majority of housework and child care.

Persistent inequality in domestic labour has many sources — all of which could be amplified during the pandemic. Gender pay gaps, particularly among parents, often cause families to privilege the careers of fathers over mothers. Societal expectations and the lack of policy supports, like access to affordable child care, pressure many women to reduce their hours or quit working in order to care for young children.

Work arrangements of heterosexual parents also play an important role in the maintenance of inequalities at home. For example, mothers do about 14 additional hours of housework each week in families where fathers are the only breadwinner, but the gap is only four hours in dual-earner families.

Increased family need, combined with commonly held gender norms and work–family arrangements may cause many families to prioritize men’s work during this pandemic. Research from both Canada and the United Kingdom, for example, shows that a significant number of mothers voluntarily left the labour force in order to take on expanded child care, educational and household needs.

Fathers stepping up

While couples may have been pushed toward greater inequality, there may be countervailing forces. COVID-19 public health orders led many men to work from home, which made many fathers more keenly aware of domestic and parental tasks suddenly thrown into their workdays.

Research on flexible work arrangements has shown that fathers who choose to telecommute tend to be more involved parents than fathers with less flexible work arrangements. However, there may be significant differences between dads who voluntarily used flexible work opportunities pre-pandemic and those who were involuntarily forced into working from home.

Increases in unemployment among fathers might have increased exposure to family needs, as well. Evidence from the Great Recession of 2007-09 suggests that many unemployed men shifted a considerable portion of the hours normally devoted in paid work into housework, child care and other domestic tasks.

Fathers’ participation in housework and child care has remained stable or even slightly improved for the majority of Canadian families in the early stages of the pandemic. At the same time, a minority of families seem poised to regress toward greater inequality in housework and child care. Overall, early trends do not foretell that gender inequality at home will deepen.

Although Canadian mothers are still doing a greater share of the work, many Canadian fathers are stepping up at home in times of crisis. Nevertheless, the rapidly changing scenarios around this pandemic will require scholars and policymakers to consider its effects on gender equality across the coming months and years.Kevin Shafer, Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of Canadian Studies, Brigham Young University; Casey Scheibling, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Sociology, McMaster University, and Melissa Milkie, Professor of Sociology, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Canadian police warn Sikh activist of threat to life as Carney announces India visit

- Cervical cancer is ‘fastest-rising’ form in Canada as doctors urge action

- Tax filing season is here. What you need to know to get the most money back

- Amid 2026 uncertainty, new data set to show how Canada’s economy ended 2025

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.