A bronze statue in Stanley Park is one of the many tributes to Harry Jerome, the legendary B.C. track star who at one point was considered the world’s fastest man.

Along with the statue, a community recreation centre in North Vancouver and an annual track-and-field tournament are named after Jerome.

While many may be familiar with the name Harry Jerome, they may not know his story.

“I just don’t think there’s been the interest in people of colour, so to speak, unless they’ve been promoted and made a big foofaraw in the United States,” Jerome’s sister Valerie said.

Jerome set seven world records in his career. In 1960, he tied the world record in the 100-metre dash, a race that is widely considered to determine the fastest man on earth.

As a teenager, he embraced sprinting, a solo sport, after experiencing unrelenting racism playing team sports.

“People in the stands with the N-word out there, but when you have people on your own team who were happy to step on your foot if they could,” said Valerie, a track star in her own right who joined her brother in representing Canada at the Rome 1960 Olympic Games.

It was the kind of hate the Jeromes encountered many times. When the family moved to North Vancouver in 1951, neighbours petitioned to keep them out.

Get daily National news

Valerie is still haunted by their first day of school.

“Hundreds of kids were waiting with rocks and we just ran back to our home,” she said. “We stayed at home for about three days.”

Racism wasn’t the only obstacle Jerome faced. In 1962, he suffered what was considered a career-threatening injury, completely severing his left quadriceps muscle.

The press, according to journalist Brian Pound, wasn’t kind.

“The media were all over Harry, calling him a quitter,” he said.

“It was really hard to bear because Harry had tremendous strength and passion and determination,” Valerie said. “And it was — just wasn’t who he was.”

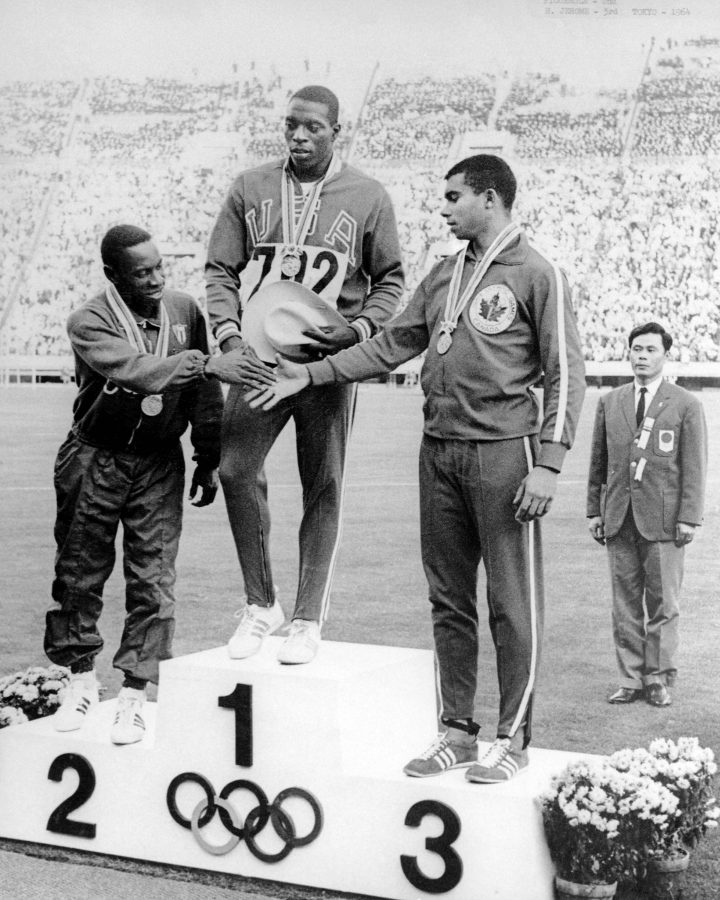

Two years later, Jerome defied the odds and won a bronze medal in the 100 metres at the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games.

After he retired from athletics, Jerome went on to promote sports and inspire future athletes. In 1982, he died from a brain aneurysm at the age of 42.

“I was honoured to have him call me a friend,” Pound said.

Pound said he hopes more people will learn Jerome’s story, one of “an incredible individual who overcame a lot of criticism, unwarranted.”

Valerie, who has worked as an educator for more than three decades, believes her brother’s story should be taught in B.C. classrooms.

“There isn’t a lot out there on Harry,” she said. ” We need to do a lot of updating of the curriculums in B.C.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.