Being a small East Coast province in the pandemic is a double-edged sword: there are fewer critically ill patients, but the supply of hospital beds is limited if the worst-case scenario materializes.

“We will have fewer beds, but we will have a lower population density too,” said Dr. Ward Patrick, the head of critical care at the Nova Scotia Health Authority – the biggest health agency in Atlantic Canada.

READ MORE: ‘Stay the blazes home,’ McNeil warns as Nova Scotia COVID-19 cases surpass 200

The 60-year-old veteran of intensive care medicine said in an interview his teams have access to an existing supply of 120 intensive care beds provincewide – each equipped with ventilators and staffed by specialized health workers.

In addition, the province’s intensive care units have been emptied by 50 per cent to prepare for COVID-19 patients, and Patrick says Nova Scotia could surge to over 200 intensive care beds as the pandemic progresses.

However, he also acknowledged there are “wild cards,” ranging from unanticipated jumps in infections to finding replacements for sick staff.

His health authority has created scenarios where 7,000 of its 23,400 staff are off due to self-isolation or illness, and Patrick said he’s aware of estimates that could go higher.

Janet Hazelton, the president of the Nova Scotia Nurses’ Union, said she believes the Atlantic provinces could face some of Canada’s biggest staffing issues.

“We don’t have enough that we can move them all over, as in some of the biggest provinces,” she said during an interview.

An outbreak from two gatherings at a funeral home last month in St. John’s, N.L. – which has generated nearly three quarters of the province’s 195 infections – illustrates another key risk when ICU beds are at a premium.

Gilles Lanteigne, the chief executive of the Vitalite Health Network in New Brunswick – which serves the province’s francophone population – says intense outbreaks in one location are the most worrying scenario for smaller health agencies like the one he oversees.

“The average age of our population is very old, and we have some regions where people are not as healthy when compared to the average region in the country,” he said in a telephone interview.

“Clustering, if that ever happens … it could cause almost a disaster. It could increase significantly the cases.”

His agency has 33 intensive care beds prepared for COVID-19 patients, with a capacity to surge in two stages to a total of 116, he said. Horizon Health Network, New Brunswick largest health authority, has 98 intensive care unit beds in place, 53 of which are currently occupied.

READ MORE: Nova Scotia extends coronavirus state of emergency, announces new support funds

Newfoundland and Labrador has 98 such beds, and four COVID-19 patients were in intensive care Friday.

Dr. John Haggie, the minister of health in the province, has said repeatedly he believes his province can cope, but this week he added: “Whether we’re right, ask me in three weeks’ time.”

Javier Sanchez, an epidemiologist at the University of Prince Edward Island’s faculty of veterinary medicine, sees some hope emerging for smaller jurisdictions.

Though he’s a veterinarian, Sanchez’s expertise has been called upon to help with COVID-19 modelling for the Island’s population of 156,000. He said with just 22 positive cases and no community transmission as of Friday, P.E.I. may be exhibiting “a unique situation.”

He said there’s little doubt a concentrated outbreak could challenge the Island’s two hospitals, which have just 17 intensive care beds and a capacity to bring on 46 additional units if needed.

However, Sanchez said unlike large urban centres, the Island, with a single bridge linking it to the mainland, has the advantage of being able to tightly restrict entry of people from other jurisdictions.

He also suggests a rural population is likelier to succeed in social distancing than large cities, and breaking the rules would be more quickly detected.

“In P.E.I., everyone knows everyone, so if you have to self-isolate and you’re going around, somebody will know you,” he said.

Lanteigne says New Brunswick’s Acadian population’s advantage is “the population is dispersed.” With the exception of Moncton, “we don’t have very large cities with high-rise buildings,” he said.

To date, there’s little clear indication of when the Atlantic provinces expect their critical care capacity will face its greatest test.

Nationally, figures cited by the chief public health officer of Canada have suggested about three per cent of the current infected population will become critically ill.

READ MORE: New Brunswick’s top doctor says coronavirus response not ending ‘any time soon’

But in the region, only New Brunswick has committed to releasing models showing the best- and worst-case scenarios it is working with, and when the peak of the pandemic is forecast.

Dr. Robert Strang, the chief medical officer of health in Nova Scotia, has said technical expertise is in short supply to create the models.

Meanwhile, Patrick, the Nova Scotia critical care director, says he hopes people realize their respect of public health directives will help determine whether intensive care systems in the region are overwhelmed.

“It’s a busy time. But we’re going to see this through,” he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 3, 2020

Questions about COVID-19? Here are some things you need to know:

Health officials caution against all international travel. Returning travellers are legally obligated to self-isolate for 14 days, beginning March 26, in case they develop symptoms and to prevent spreading the virus to others. Some provinces and territories have also implemented additional recommendations or enforcement measures to ensure those returning to the area self-isolate.

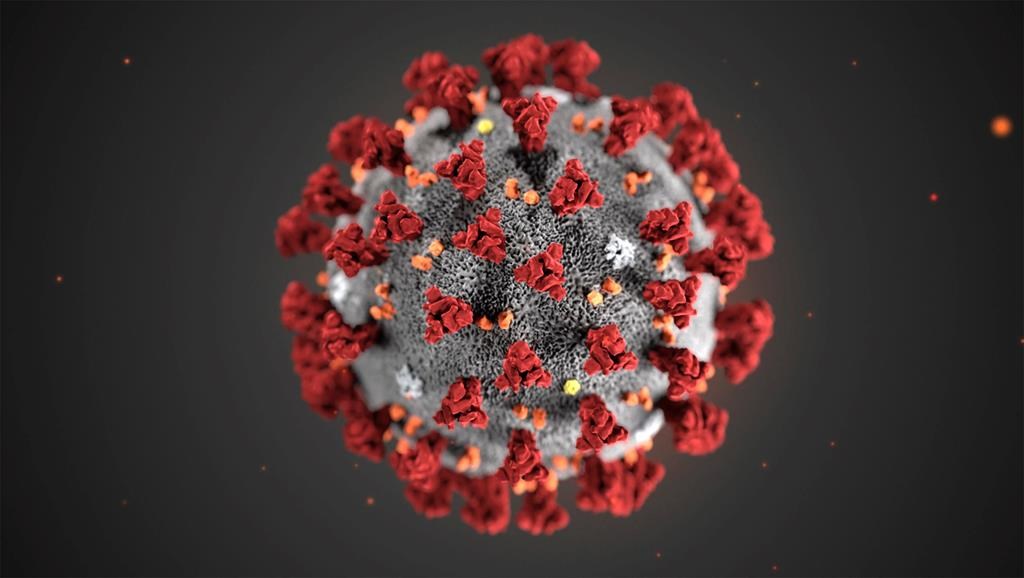

Symptoms can include fever, cough and difficulty breathing — very similar to a cold or flu. Some people can develop a more severe illness. People most at risk of this include older adults and people with severe chronic medical conditions like heart, lung or kidney disease. If you develop symptoms, contact public health authorities.

To prevent the virus from spreading, experts recommend frequent handwashing and coughing into your sleeve. They also recommend minimizing contact with others, staying home as much as possible and maintaining a distance of two metres from other people if you go out.

For full COVID-19 coverage from Global News, click here.

Comments