Three days after a gunman opened fire inside a mosque in Quebec City in 2017, worshippers walked through the mosque’s doors again.

It was a sign that those at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec, and Muslims across Canada, wanted to find a way back to normalcy.

There were blood stains on the carpets, and bullet holes in the wall and windows.

Ahmed Elrefai, a man who prayed at the mosque, pointed to dried, dark red blood on the floor where his friend had been shot.

“The message is that we will still pray, even with blood on the floor,” he said.

On Jan. 29, 2017, a Sunday evening, six Muslim men were killed at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City. The massacre resulted in six widows and left 17 children without fathers.

Three years later, the path to recovery for Muslim Canadians has been complex, says Amira Elghawaby of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network.

“For a moment, it seemed that Canada and governments and society was ready to meet the challenge of this type of discrimination,” Elghawaby told Global News.

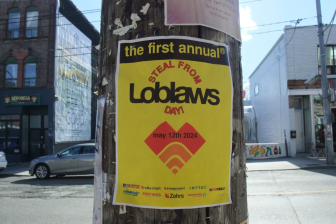

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

“But then, that moment sort of dissipated.”

Despite the calls to action and the promises, in the days, months and years after the Quebec mosque shooting, Islamophobia in Canada did not stop.

During the year of the shooting alone, there were 349 incidents of police-reported hate crimes against Muslims in Canada. That was a jump of 151 percentage points from the previous year of 2016, which saw 139 such reports.

Preliminary numbers for 2018 show there were 173 such hate crimes.

Those represent the latest released numbers on police-reported hate crimes in Canada, but they don’t tell the full story.

Statistics Canada notes itself that the majority of hate crimes in Canada, about two-thirds, go unreported.

While preliminary data is released earlier, the fact that there is roughly a two-year lag on the release of detailed hate crime data is problematic, Elghawaby said.

“There is no intersectionality when it comes to the data, so we don’t know if people are being targeted for multiple identities. We know that not every instance of what we would perceive as a hate crime or hate incident is captured.”

Better data on hate crimes would give a better picture of how communities in Canada are being treated, Elghawaby said.

Statistics would shed greater light on Islamophobia in Canada. But Ayesha S. Chaudhry, the Canada research chair in religion, law and social justice at University of British Columbia, added many still struggle to acknowledge racism and Islamophobia exist in Canada.

Chaudhry was part of hearings on M-103 in Ottawa, a non-binding private members’ motion put forth by Liberal MP Iqra Khalid that called on the government to condemn Islamophobia and other forms of systemic racism and religious discrimination.

She said many conversations at the hearings, and beyond, focused on questioning whether Islamophobia was even a problem.

“What is Islamophobia? Is it even a thing? Does it even exist?” she recalled.

“Instead of thinking about the people that had clearly been targeted and murdered because they were Muslim, and having a conversation — what is it about our culture and our country, what is it about our education system, what is it about our media that fosters this kind of hatred against Muslims — the conversation was, ‘Is this even a thing?’”

While the motion was ultimately passed, it did not get the support of Conservative MPs. It also led to nationwide protests, while Khalid reported receiving death threats over her support of the motion.

Years after the M-103 debate, Chaudhry said Canadian politicians have shown a lack of understanding on Islamophobia in other aspects, as well.

She pointed to a contentious Quebec law that forbids certain public sector workers from wearing religious symbols at work. The law, commonly referred to as Bill 21, is facing legal challenges by several advocacy organizations, including the Canadian Civil Liberties Association and the National Council of Canadian Muslims.

During the federal election campaign in 2019 — the first to take place after the Quebec shooting — Chaudhry noted Islamophobia was not widely discussed. She added federal leaders also often tip-toed around condemning Bill 21 or promising action.

“That’s a real problem, when you have a political climate where speaking out against Bill 21 is not politically expedient and might in fact hurt your political chances,” she said.

When it comes to truly addressing Islamophobia, Sidrah Ahmad-Chan, the founder of Rivers of Hope Project on Islamophobic Violence, says Canadians need to look online, where hate is most rampant.

A Statistics Canada report, published in May 2019, included a brief section on online hate, explaining that between 2010 and 2017 there were 364 police-reported cyber hate crimes in Canada. The statistics included only online hate that was reported to police, then found to be a criminal violation.

Muslims encountered the most online hate at 17 per cent, followed by hate based on sexual orientation at 15 per cent. Fourteen per cent of the cyber hate crime reports were aimed at the Jewish population, and 10 per cent were targeted at black Canadians.

Ahmad-Chan, however, noted online hate is much more widespread than most Canadians even realize.

“Searching YouTube videos, online content, online forums, you can enter a world that is actively demonizing Muslims at a level that is inciting violence,” she said.

Ahmad-Chan explained countering this online hate is complicated, but part of the solution is educating youth — before they find themselves being influenced by such content.

“What are we doing to assist them? Where are these messages coming from? Literacy is something that really should be universally provided.”

Other anniversaries in Canada, such as the Dec. 6 anniversary of the Montreal Massacre at École Polytechnique, when 14 women were killed, are commemorated annually.

Ahmad-Chan said that contributes to public awareness about issues, such as gender-based violence in the case of Dec. 6, which is now known as the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women in Canada.

“I’m hoping that there will be a similar dignity given to this date, and kind of a permanent education to go along with it,” she said.

“It’s the first massacre of its kind in a mosque in North America.”

Elghawaby agreed, saying that would help cultivate a more ongoing conversation about Islamophobia in Canada. There have been calls and petitions to have Jan. 29 be designated as a national day of remembrance and action, but that has yet to happen.

“We need to make sure that those six men did not die in vain,” Elghawaby said.

— With files from The Canadian Press

Comments