Amid temperatures closing in on -40 C, both sides of a dispute over a proposed natural gas pipeline through northern B.C. are digging in.

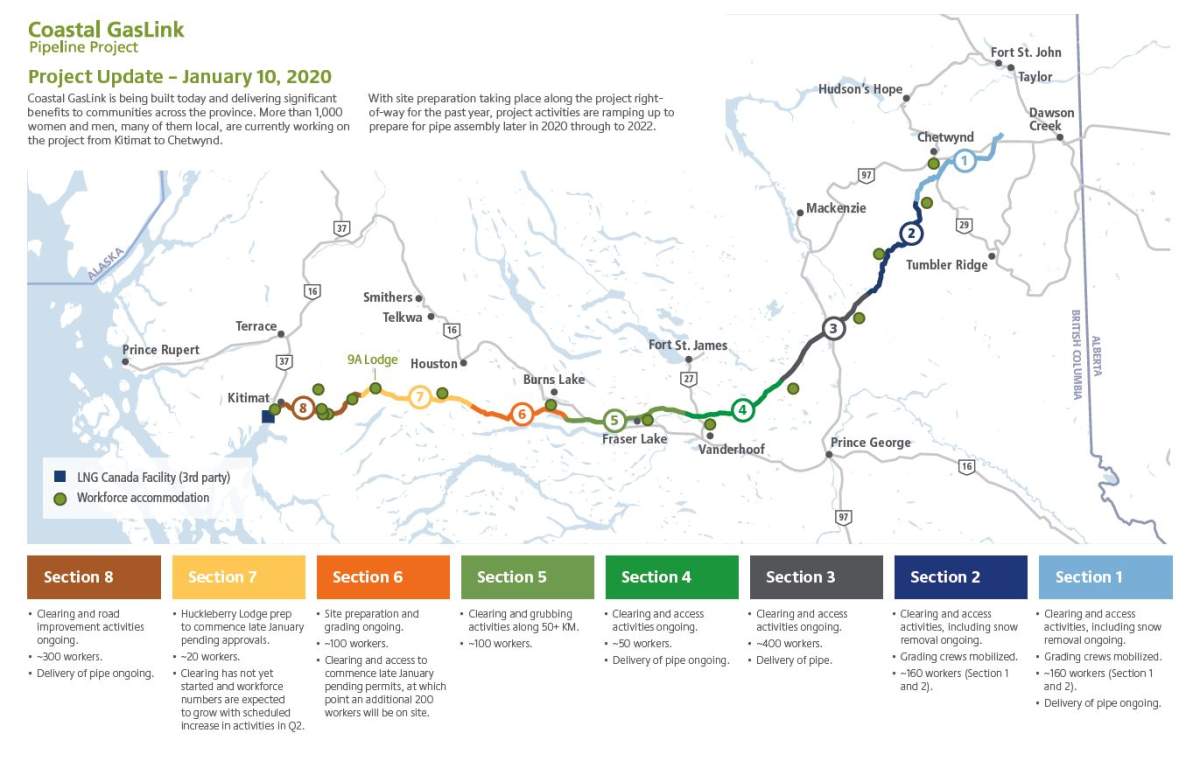

The RCMP moved in Monday to set up an “access control checkpoint” over a key service road leading to a Coastal GasLink work site near Houston B.C. The work is part of a $6.6 billion project meant to feed the $40 billion LNG Canada export plant being built near Kitimat.

A B.C. Supreme Court injunction issued late last month ordered that any and all obstacles to pipeline construction be removed, though it remains unclear when or if police will enforce it.

Hereditary chiefs with the Wet’suwet’en Nation oppose the project, saying it violates Indigenous law and does not have consent.

The Wet’suwet’en and supporters have set up their own camp along the road, and allegedly cut down trees to block access.

“We’re on guard here. And just ready for any scenario, really,” said Sabina Dennis of the Wet’suwet’en Dakelh Cariboo Clan.

“I’d like people to know that we are under Wet’suwet’en law where we stand. I feel like I myself am under Wet’suwet’en law.”

The RCMP say the checkpoint is to “mitigate safety concerns,” and that chiefs, government officials, accredited journalists and people delivering food will be allowed through.

But the checkpoint has already drawn heavy criticism.

“A police exclusion zone smacks of outright racism and the colonial-era pass system sanctioned by the so-called rule of law, which our people survived for far too long,” said Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) in a statement Tuesday.

The UBCIC said the BC Civil Liberties Association is filing a legal complaint against the checkpoint, arguing that police had already denied access to two people delivering food.

Get breaking National news

The Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) is also speaking out against the checkpoint, warning that police could use the exclusion zone to prevent media from covering RCMP enforcement of the injunction.

“We do not want to see a repeat of last year’s behaviour, when the RCMP used an exclusion zone to block journalists’ access, making it impossible to provide details on a police operation that was very much in the public interest,” said CAJ President Karyn Pugliese in a statement.

Police were criticized for their actions in enforcing a separate injunction in the same area last year.

A December report in the U.K. newspaper The Guardian suggested RCMP discussed deploying snipers and putting children into social services during that action. Police have denied that report.

A reporter for B.C. online publication The Tyee took to social media Monday to say she’d been denied access to the site.

On Tuesday, Coastal GasLink sent a letter to Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Na’moks renewing the company’s request or a face-to-face meeting.

“As you know, we have been granted an interlocutory injunction with respect to accessing work areas in and around the Morice River bridge and have the legal right to undertake construction,” wrote CGL president David Pfeiffer.

“However, our preference continues to be resolution of issues through meaningful dialogue. We believe that by working together, we can address the interests of the Office of the Wet’suwet’en while continuing to provide significant benefits to the Wet’suwet’en and other Indigenous communities.”

The Wet’suwet’en have to this point refused a meeting, and say they want to meet with the provincial and federal governments.

Ari L, a Wet’suwet’en supporter behind the checkpoint, told Global News she was there to be a pair of eyes on whatever transpired.

“In my mind I was bracing myself for the worst case scenario, but I came here to bear witness to what could happen,” she said.

“I think it’s really important, especially under a climate emergency, for us to support each other.”

B.C. Premier John Horgan has vowed the pipeline will be built, saying it had all necessary permits and that the B.C. Supreme Court had been clear on the company’s legal right to access the site.

Coastal GasLink has also secured the support of all 20 elected Indigenous councils along the pipeline route.

However Wet’suet’en opponents say only hereditary chiefs have the authority to make decisions over unceded land.

“The band council was designed to take the power away from people. And the hereditary system was made to restore power to the people,” said Dennis.

“This is going to become more of an issue for B.C. This is all unceded territory.”

- B.C. 2026 budget ‘neither’ big cuts nor tax increase, minister says

- Former Conservative leader John Rustad says he’s not running for his old job

- Parts of B.C.’s South Coast set to see snow-rain mix with ‘rapidly changing’ travel conditions

- Survivor of one of Canada’s first school shootings reflects on Tumbler Ridge grief

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.