When NASA launches the first mission in its next phase of lunar exploration next year, there will be a significant Canadian contribution on board.

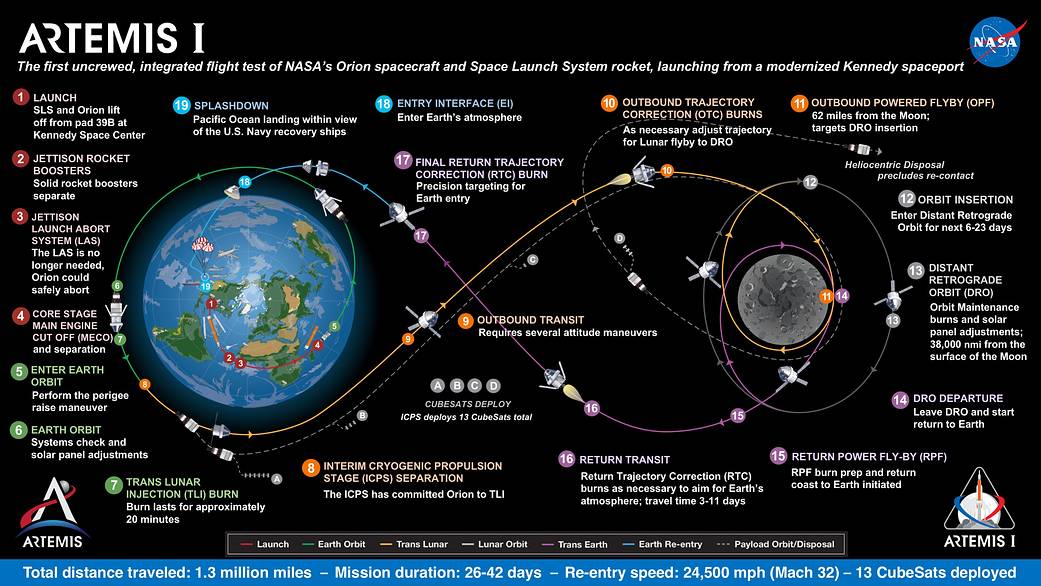

Artemis I is the first of several missions in what amounts to NASA’s first major moon push since the Apollo missions decades ago.

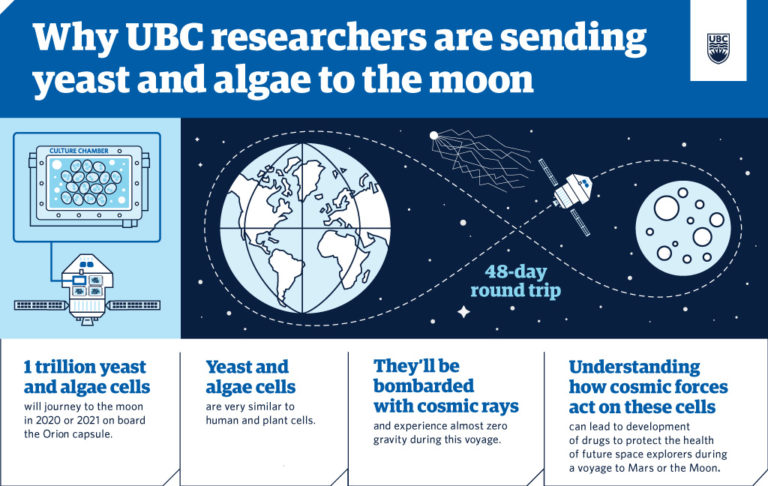

The uncrewed mission will spend 48 days in space, including multiple orbits around the moon.

As it does so, it will be carrying a trillion yeast and algae cells inside the Orion capsule, which researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) say could one day prepare humans safely to spend longer periods of time in space.

One of the major challenges would-be space travellers will face is bombardment from cosmic radiation.

That radiation is prevalent in space, but humans are protected from it by Earth’s atmosphere.

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station are protected from solar radiation due to the installation’s position and shelter from solar winds, explained UBC’s Corey Nislow, director of the UBC Sequencing and Bioinformatics Consortium.

On a long space mission — say to Mars — that equation changes.

“This radiation comes from solar flares and ionized galactic particles. It hurtles across space at incredible speeds — and it can pass through spacecraft like a hot knife through butter,” said Nislow.

Nislow has been working with yeast — which shares about 50 per cent of its genes with humans — as a stand-in to test the effects of cosmic radiation and with the goal of creating drugs or therapies that help bolster human resistance to it.

Over the summer, his team simulated the effects of cosmic radiation on 6,000 strains of yeast. Scientists dosed the cells with the amount of radiation an astronaut would be exposed to after a year on Mars.

Nislow and researchers from Colorado, Germany and Japan identified 10 genes in yeast that allowed it to survive the radiation.

Get daily National news

Those 10 genes have human counterparts, which researchers now plan to insert into yeast cells and repeat the experiment — this time in space.

“Ultimately, we should be able to find a way to boost the levels of those protective genes in humans, whether through specialized drugs, nutrition or lifestyle routines,” said Nislow.

“There’s a very real possibility that we’ll end up with a drug or drugs to help humans avoid damage from space radiation.”

NASA hopes to launch the Artemis I mission, which will use the agency’s massive new Space Launch System rocket and the new Orion spacecraft by November, 2020.

The mission is the first integrated use of the two systems, which will eventually be used to return astronauts to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years, via the Artemis Program.

Artemis II is planned for 2022, and will put humans in orbit around the moon for the first time since Apollo 17 in 1972.

It will also begin the creation of the Lunar Gateway, a space station meant to allow astronauts and equipment to move back and forth between the moon and Earth regularly, and act as a future waypoint for Mars exploration.

The Canadian Space Agency has signed on to that project as a partner, with a $2-billion, 24-year commitment.

Artemis III, planned for 2024, is slated to see humans descend to the moon’s surface for the first time since that final Apollo mission, and will include the first woman to walk on the moon.

— With files from the Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.