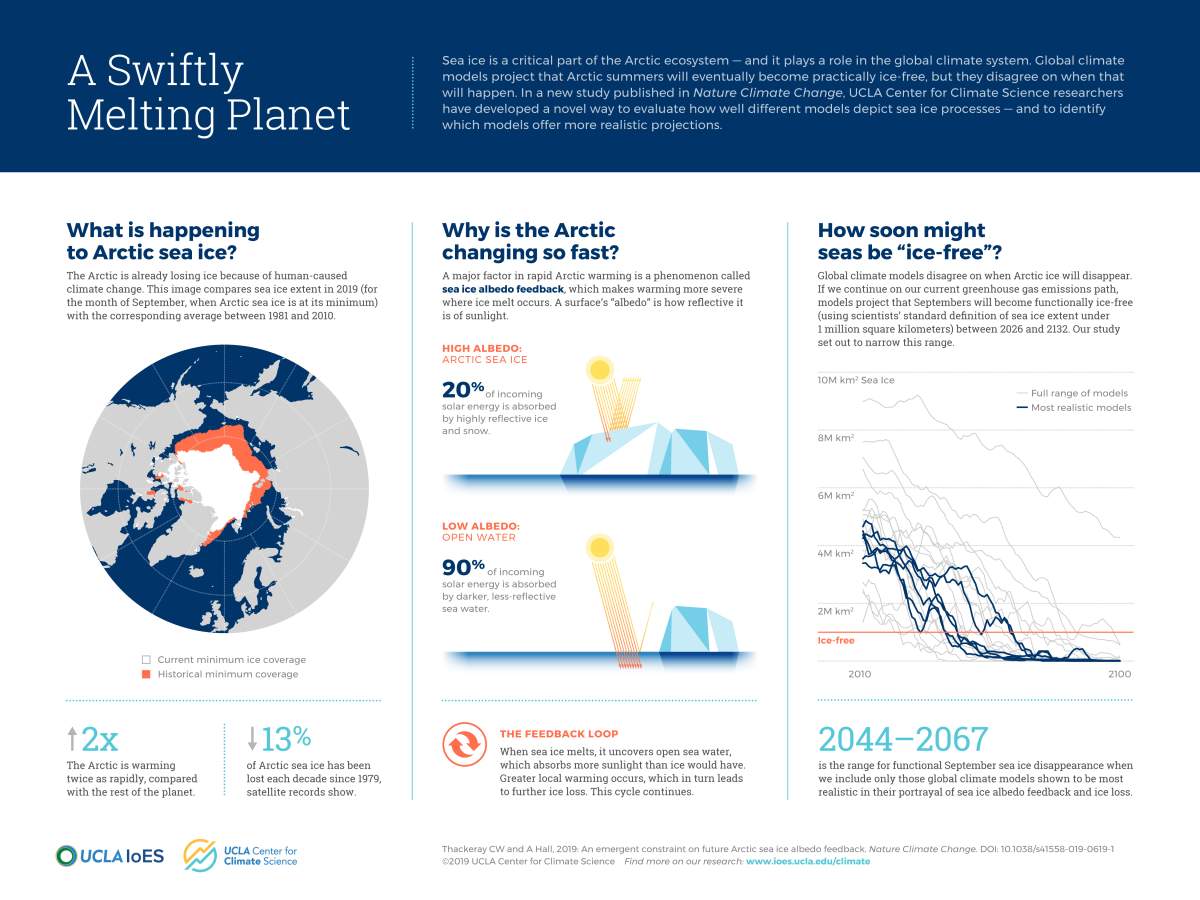

Researchers at the University of California’s Center for Climate Science say a “functionally ice-free” Arctic can be expected within the next 50 years.

A study published in the journal Nature Climate Change predicts that if the Earth continues at its current rate of greenhouse gas emissions, Arctic sea ice would regress to levels not high enough to perform its function of reflecting heat back — levels that can be reached as early as September 2044 and no later than 2067.

Previous models of sea ice melt have disagreed widely on a consensus for prediction, with some projecting an ice-free September by 2026 or one as late as 2132, according to a press release from UCLA.

September is used as the benchmark for models because it’s the time when sea ice levels are at their lowest, due to the melt from summer heat.

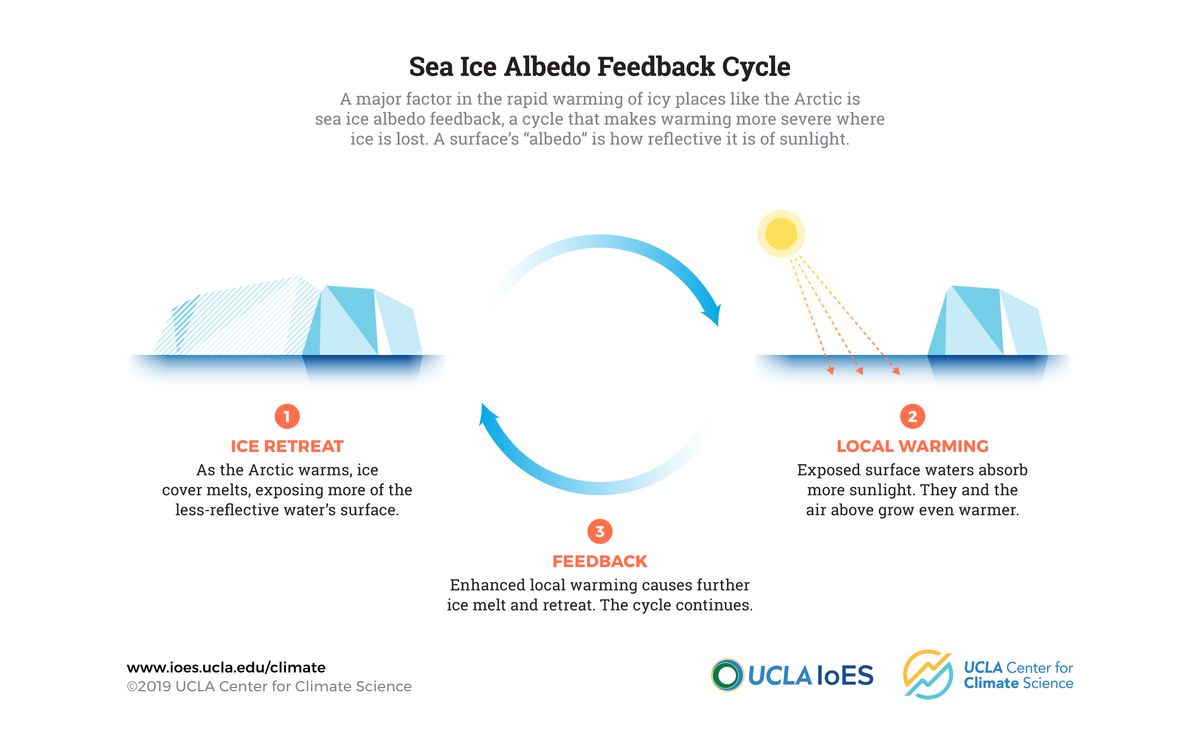

Chad Thackeray, the study’s lead author, told Global News that one reason why predictions differ so much was in how they represent the sea ice Albedo feedback cycle — a process whereby current sea ice retreat reveals a darker seawater surface in the Arctic, allowing more sunlight to be absorbed and thus accelerating ice melt.

“It’s a positive feedback cycle that amplifies an initial change in ice and can cause greater warming,” said Thackeray.

Thackeray and co-author Alex Hall made use of a new method to model their prediction of sea ice melt.

Using 23 different models of ice melt and comparing them to about 30 years of satellite data, Thackeray and Hall isolated the most consistent results to narrow the range of their prediction, picking the best six overall.

Get breaking National news

Knowledge of the Earth’s melting sea ice is not new. According to a press release from UCLA, satellite images have shown that since 1979, sea ice levels in September have been declining at a rate of 13 per cent every decade.

Currently, sea ice in September averages a surface area minimum of five to six million square kilometres. Thackeray said that once the sea ice melts to an area under one million square kilometres, the Arctic would then be defined as “functionally ice-free.”

“So once we get below this one-million kilometres squared, it’s seen as somewhat of a tipping point, where it might take a substantial amount of time for the ice to be able to grow back after its completely disappeared,” Thackeray told Global News.

Thackeray’s study did, however, have its limits — geographic data was limited to sea ice in the area 70 to 90 degrees North latitude, according to Thackeray.

“There is a certain portion of the Canadian Arctic that’s cut off, say like south of the Northwest Passage route,” said Thackeray.

“Essentially just to simplify our study area, you have less land to interact with.”

Despite the limit of the area study, Thackeray said that the results of the study are still the same regardless of the measurement.

“Those aren’t the areas that are holding on to the ice the longest in the future. It’s areas right around the northern coast of Greenland and the far north Canadian archipelago,” said Thackeray.

“These areas below 70 aren’t the areas that hold on the ice the longest anyways — they’ll be free of ice even sooner than that.”

When asked when or how long the sea ice in the Arctic would take to grow back, Thackeray responded with, “We don’t have a scenario for re-growth.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.