Editor’s note: this story has been updated to clarify that B.C. officials already use lidar technology to accurately measure elevation for sea level rise flooding models.

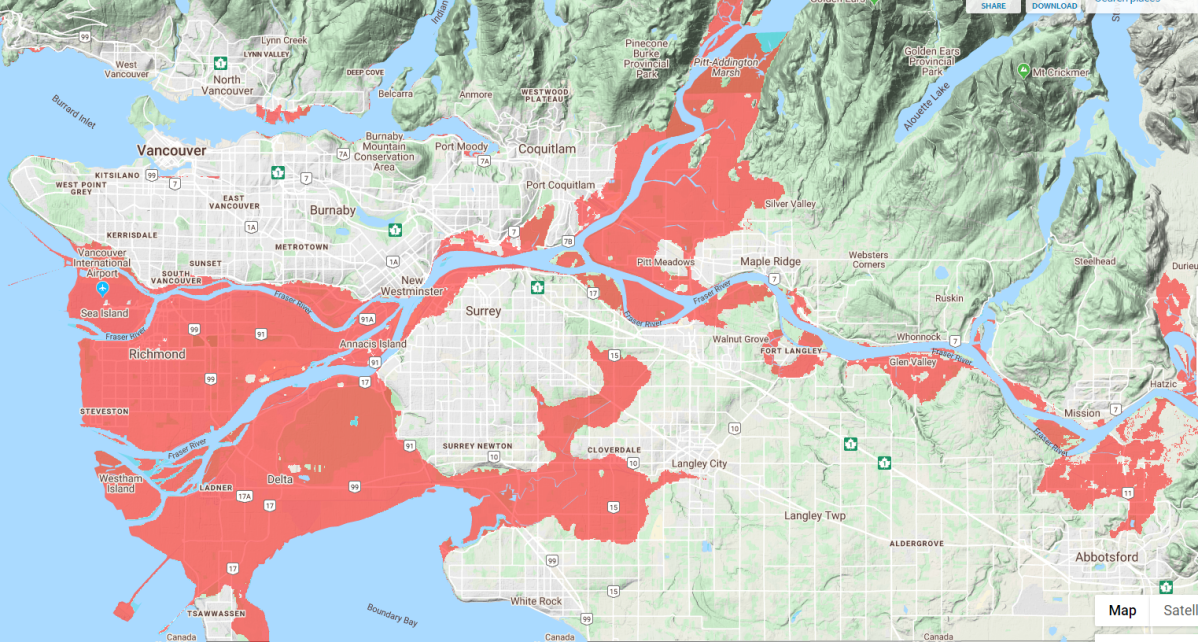

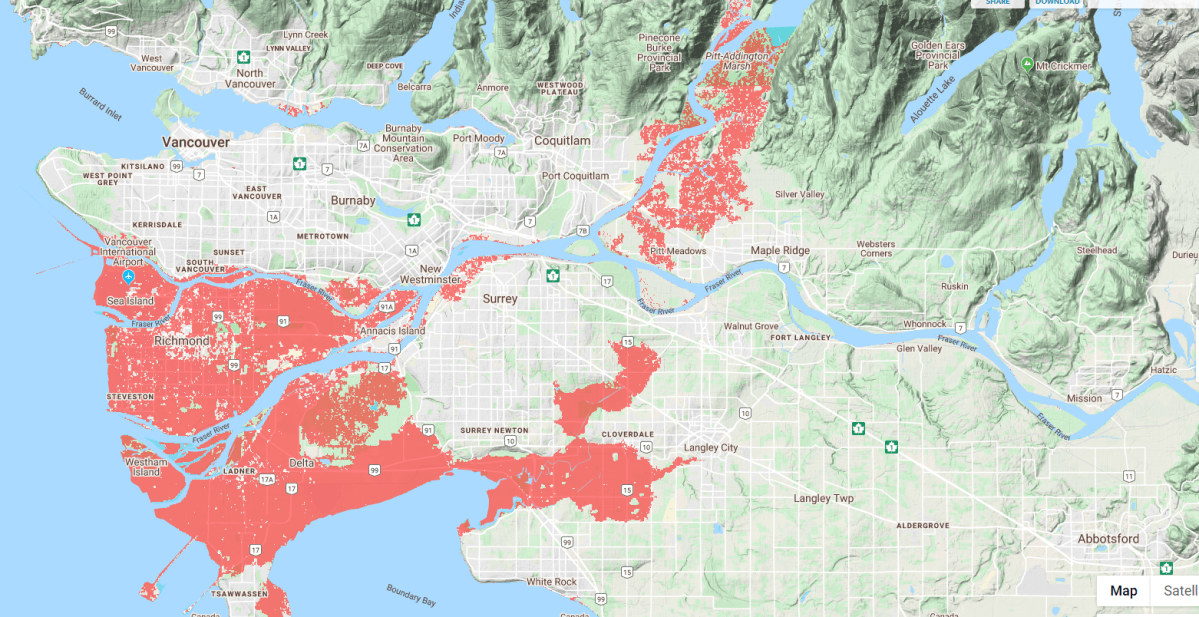

A new analysis of climate change-driven sea level rise is helping highlight the risks of flooding that the Lower Mainland could face in the years to come.

The data comes from a peer-reviewed study by non-profit Climate Central, published in the journal Nature Communications, which found that deficiencies in mapping data appear to have masked the extent of the risk caused by rising sea levels.

The study found that the most commonly used mapping dataset overestimates coastal elevation by several metres because it read treetops and building roofs as the “ground”; using AI and millions of samples, it purports to have cut that error down to a few centimetres, said lead author Skott Kulp.

“And when we do that, we find that the global coastal vulnerability to coastal flooding is three times worse than we had previously imagined,” he told Global News.

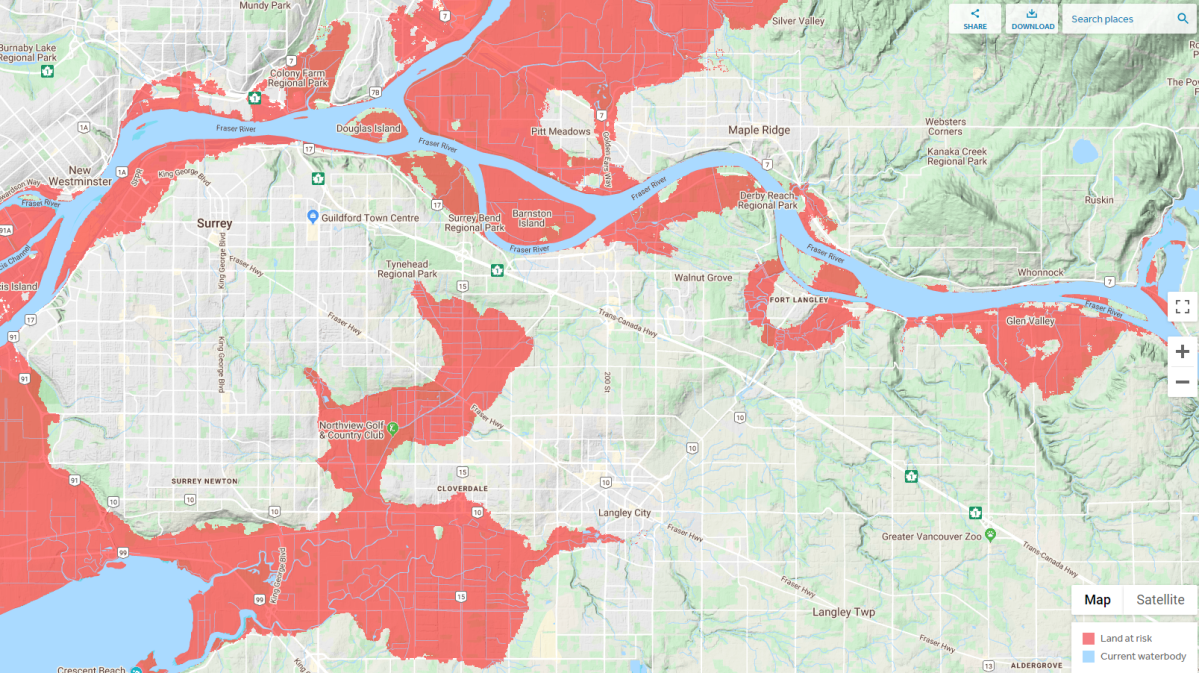

The findings are available in an interactive map that allows users to toggle between time frames, cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, and optimism of sea level rise estimates.

The increased risks will be disproportionately felt in Asia, where there are large populations of people living in low-lying coastal-adjacent communities, and where officials may not have access to the best mapping tech. It estimates 93 million people in China, 42 million in Bangladesh, and 36 million in India would face serious flooding by 2050.

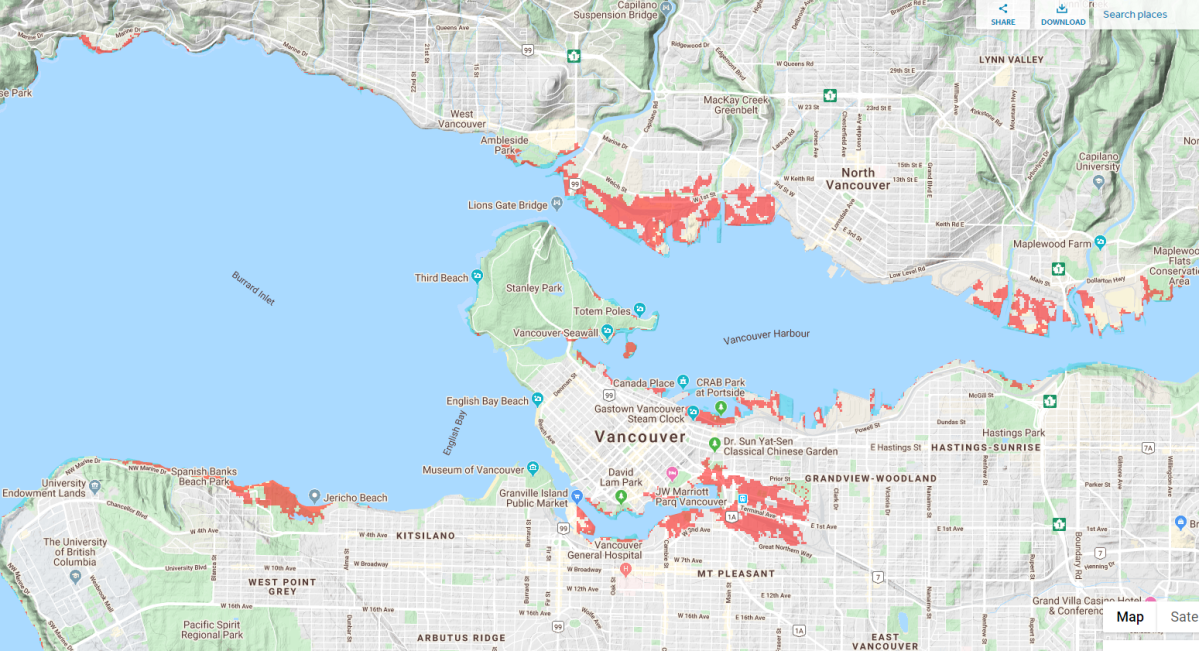

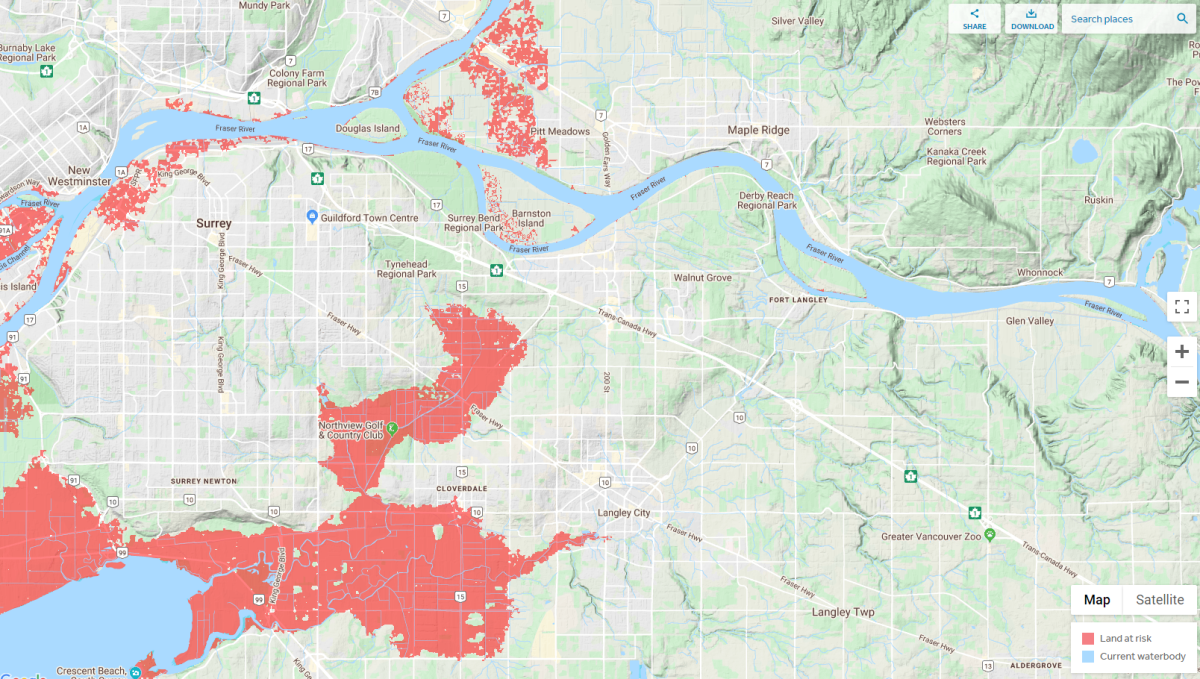

For Lower Mainland residents the study offers an easy to understand look at how climate change driven flooding could impact the region.

Many areas of water adjacent to North Vancouver, as well as much of Vancouver’s False Creek Flats and West Point Grey beach areas would be vulnerable, according to the projections.

What’s more, major areas along most of the Fraser River — including North Surrey, Pitt Meadows, Fort Langley, Glen Valley and a large flood plain in Abbotsford — could also be vulnerable to flood events, it projects.

Tamsin Lyle, a flood management specialist and principal with Ebbwater Consulting said the study doesn’t change planning models for officials in B.C., who already use lidar technology to effectively measure elevation.

Get daily National news

But she said it offers an important reminder of the challenges climate change is bringing both globally and locally.

UBC climate scientist Simon Donner added it’s important to recognize the projections don’t mean our city will be under water in 2050, but they herald a need to prepare for change.

“When we do have those extreme high tides, usually in December and January that’s the extreme right now,” he said.

“It’s going to become ‘normal’ in the future. What’s ‘extreme’ in the future is going to impact land much further inland.”

Donner added that flooding doesn’t mean areas will become uninhabitable, noting that there are cities around the world with land below the high-tide line.

“However, it does mean you need to adapt and you can’t do it at the last minute,” he said.

“So it’s really important that we’re planning now for how we want our city to look 30 years from now, … any infrastructure, buildings, we’re expecting them to be there to be used in 2050.”

B.C.’s local government flood hazard guidelines, drafted in 2004, recommend a minimum flood construction level of 1.5 metres above the natural boundary of the sea.

The province’s own 2013 Sea Level Rise Adaptation Primer for regional managers recommends planning for sea level rise of about one metre by the end of the century, and 50 centimetres by 2050.

Lyle said responsibility for flood mitigation in B.C. lies with municipalities, adding that it’s a “mixed bag” when it comes to levels of preparation.

Lyle helped write the City of Vancouver’s own sea level rise plan and said the city, along with Surrey, has been at the forefront of dedicating resources and realistic planning to addressing the issue.

Vancouver, for example, now requires all new coastline projects to incorporate flood risk information.

However the region remains vulnerable.

Lyle said the region faces two major challenges in preparing for sea level rise and attendant flooding. One is coordinating diverse municipalities with differing levels of resources and commitment to climate adaption.

Tamsin pointed to work by the Fraser Basin Council as an area where cross-jurisdictional work to prepare is underway. The organization produced a report in 2016 warning of “significant risk” of a major flood event with a more than $20-billion price tag in the region, and is currently working on a regional strategy to reduce risk.

But she said the bigger challenge is recognizing that some of the old ways we’ve dealt with flooding — like dikes — may no longer be cost effective in the future.

“At some point, the dikes are going to be so high that they’ll actually collapse under their own weight, so they no longer become the solution,” she said.

But she said it may take extreme weather events reaching areas that traditionally haven’t been hit to move the needle, noting that places like Vancouver and West Vancouver that have already seen flood damage have been quicker to act.

“For example, thoughtfully removing some of the things we care about most out of the coastal flood plains over time into the mountains. Not tomorrow. Like over the next decade.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.