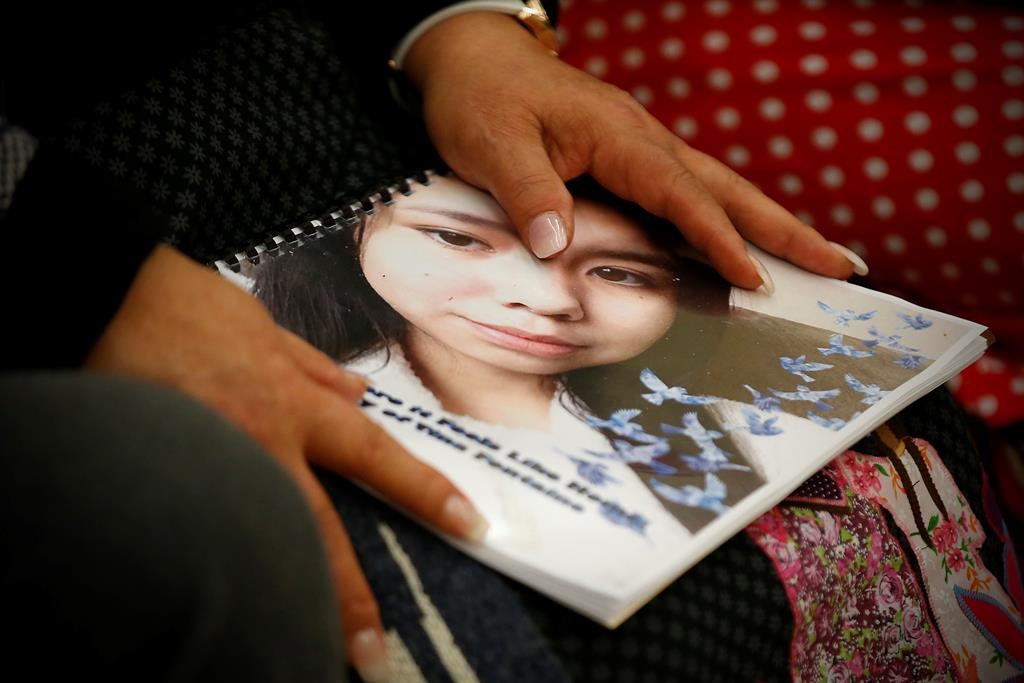

Manitoba’s advocate for children and youth says a lot more needs to be done if the government is to save children in care from the grim reality of an Indigenous teenage girl whose body was found in a river.

“Awareness is the first step,” Daphne Penrose says of her report, released in March, into Tina Fontaine’s death.

“The big question becomes: What are you going to do to change the services for children and youth in Manitoba to make sure those situations don’t occur again?”

Penrose’s report into the life and death of Fontaine, who was 15 when her body was found in Winnipeg’s Red River five years ago, outlined how social workers and others failed the girl even as it became clear she was spiralling downward and her life was at risk.

The report included five recommendations touching on justice, education, mental health and child welfare. Penrose said at the time that the province needed to act quickly or more children would die.

The province committed to releasing updates publicly on its progress, but a report from June was not available until recently.

Officials cited a pre-election blackout ahead of the Sept. 10 provincial vote. The update says the government has shared the advocate’s recommendation on changes to student suspensions and expulsions with a committee looking into education in the province.

It also says the province has ongoing reviews into youth mental health services and how child welfare and the justice system are intertwined.

Get daily National news

“We also know that simply increasing service funding is not the answer,” the update says. “We must look at short-, medium- and long-term projects critically so we can address … the needs of people seeking treatment now while building a stronger system in the months and years ahead.”

The province’s Families Department says in an email that the government is reviewing feedback from the advocate’s office and will continue to provide regular updates on its progress.

Fontaine’s mother was 17 and still a child in care when her daughter was born. Both of her parents struggled with addiction.

When Fontaine was five, she went to live with her great-aunt Thelma Favel from the Sagkeeng First Nation.

Fontaine’s life was relatively stable until her father was murdered in 2011.

Favel, who was still her caregiver at the time, tried to get her help through victim services. But Fontaine never received counselling.

In June 2014, Fontaine went to Winnipeg to reconnect with her mother.

The teen was soon homeless, developed addictions and was sexually exploited. She reached out for help several times, but on more than one occasion, there were no shelter beds available.

Her 72-pound body, wrapped in a duvet cover and weighed down by rocks, was pulled from the river two months later.

Penrose says she’s been encouraged by the actions taken by victim support services for children. One such initiative has been creating template letters to make sure information is clear and consistent for victims in traumatic situations in the justice system.

Other positive changes have included expanding kits to help kids develop healthy coping strategies. But many responses have been lacking in detail, she says.

Penrose’s office sent the government a slew of questions. The advocate for youth says she needs to know when reviews will be completed and has to have information on funding and other data to understand if the government is truly acting on the recommendations.

“To be able to monitor the compliance … allows us to ensure that these reports don’t sit on a shelf collecting dust.”

Penrose says she understands the government needs time to adapt, but she expects its progress reports to include more information in the future.

She adds that Manitobans need to know what’s being done to help children so her office plans to begin publishing analyses of the government’s work online next month.

“The outcomes for kids can be quite dramatic and traumatic,” she says.

“It is important that we always continuously improve the services that are being provided to kids in their ever-changing world.”

Comments