A British Columbia court is set to rule Friday whether the province can restrict shipments of diluted bitumen through its borders, in what will be a crucial decision for the future of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

The province filed a reference question to the B.C. Court of Appeal that asked whether it had the constitutional authority to create a permitting regime for companies that want to increase their flow of oilsands crude.

B.C. argued the law is aimed at protecting its lands, rivers and lakes from hazardous substances, but Alberta and the federal government have said the goal is to delay or block the pipeline expansion.

WATCH: (Aired April 18) Trans Mountain pipeline decision extended to June 18

“It’s a little bit strange to argue that diluted bitumen is such a dangerous product that it needs to be regulated, but it’s only (an) entity that wants to increase its flow that falls under this particular scheme,” said Eric Adams, a University of Alberta law professor.

“Guess what that entity is? It’s the Trans Mountain pipeline.”

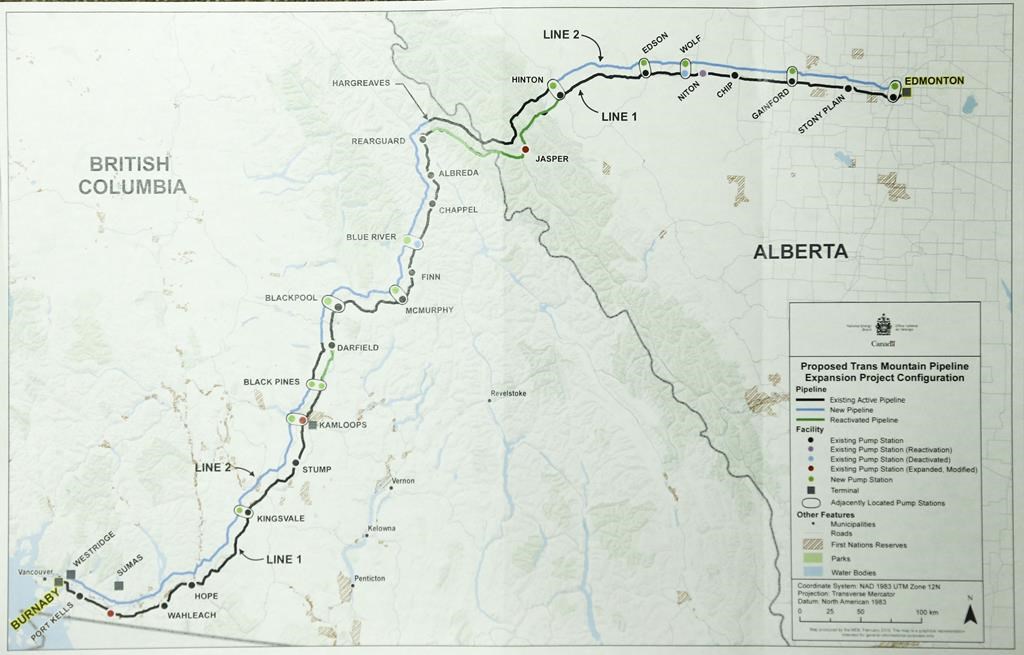

The Trudeau government has purchased the pipeline and expansion project for $4.5 billion. Alberta sees it as an essential development to get more oilsands product to overseas markets, but B.C. opposes a three-fold increase of diluted bitumen through its territories.

If B.C. is given the green light to enact amendments to its Environmental Management Act, it would be able to require Trans Mountain Corp. to obtain a so-called “hazardous substance permit” for its expansion.

An application for a permit would have to detail the health and environmental risks of a spill, the measures in place to minimize those risks and financial measures, including insurance, to ensure capacity to respond.

Get daily National news

WATCH: (Aired March 18) B.C. bid to control Trans Mountain shipments

The corporation would also have to establish a fund for local governments and First Nations, giving them capacity to respond to a spill and agree to compensate anyone involved in responding.

A provincial public servant would also be empowered to add conditions to the hazardous substance permit, as long as they were necessary to protect the environment and human health.

If Trans Mountain fails to comply, the public servant could, with notice, suspend or cancel the permit.

Adams, an expert in constitutional law, said federal and provincial governments have overlapping powers over environmental issues. However, he said everyone concedes that the federal government has exclusive jurisdiction over interprovincial pipelines.

The question before the Appeal Court is how that power relates to B.C.’s authority to regulate what it says is a toxic substance within its borders, he said.

“They’re not actually regulating the pipeline at all, (B.C.) would say. They’re regulating a dangerous product,” he said. “Even if it happens to be in B.C. by virtue of a pipeline, that doesn’t take away B.C.’s jurisdiction.”

WATCH: (Aired Feb. 22) What are the next steps in getting Trans Mountain built?

But Adams noted that Premier John Horgan said on the campaign trail that he would use “every tool in the toolbox” to stop Trans Mountain. Once in power, Horgan softened his language to say he would use every tool to protect B.C.

“It’s not very difficult to connect the dots between this proposed legislation and a political attempt to stop a pipeline that falls within federal jurisdiction,” Adams said.

Canadian courts look at the full context when they’re evaluating the dominant purpose of a law, he added. So even though those who drafted the B.C. legislation worked carefully to try to write it constitutionally, the public comments of government officials still matter.

B.C. announced it would enact the legislative amendments in January 2018, sparking a trade war with then-Alberta premier Rachel Notley, who retaliated by banning B.C. wine from her province.

Horgan eased the tension by promising to file a reference case that examined the constitutionality of the law, prompting Notley to end the wine ban in February 2018.

The Appeal Court heard the case in March. Saskatchewan, Trans Mountain Corp. and Enbridge Inc. were among those who argued against B.C.’s proposed permitting regime, while First Nations, cities and environmental groups supported it.

It might appear contradictory that B.C. recently filed a court challenge of Alberta’s “turn off the taps” law that would give Premier Jason Kenney’s government the ability to restrict gas shipments to B.C., said Adams.

However, he said the B.C. government is on solid legal footing there because of a section in the constitution that prevents provinces from discriminating on supply or pricing to other areas of Canada.

The story might not end with the ruling on Friday, Adams said. Either side could take the reference case to the Supreme Court of Canada, which must automatically agree to hear it.

Comments