A former B.C. casino employee says she regrets signing an $18,000 “gag order” with Great Canadian Gaming that prevented her from speaking at a public hearing regarding the company’s application to open a casino in Coquitlam, B.C.

Muriel Labine, who was a dealer supervisor, said that in June 2000, she resolved to speak at a Coquitlam town hall meeting after coming to the decision that she could no longer work in the company’s Richmond casino because she feared violence from gangs and loan sharks.

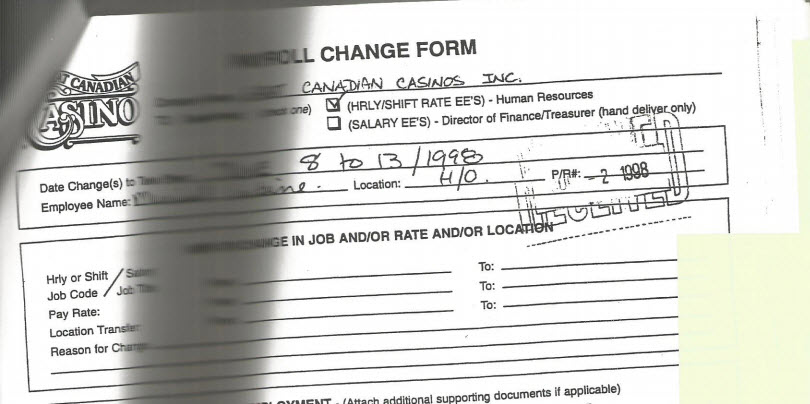

She planned to also inform the public about Great Canadian’s involvement in Coquitlam’s 1998 municipal election.

“I was asked to go and work on Jon Kingsbury’s campaign for mayor,” Labine said. “I think the company was there because they wanted Jon Kingsbury elected.

I went to that hearing with the intention of speaking out about the gangs and about the connection between Jon Kingsbury and Great Canadian.”

WATCH: Ex-B.C. casino worker blows whistle on timeline of alleged money laundering

Labine said she struggled with the decision to speak because she was afraid.

“This is not safe for me, this is not safe for my family,” Labine recalled thinking. “But yet, my conscience was telling me, ‘You’ve got to step up.’”

“In those early years, when the gangs first arrived in the casino, that was the training ground for what was to come. And I think, realistically, it could’ve been stopped way back then.”

But on June 22, 2000, when she attended the town hall, she says she was spotted by a Great Canadian manager and asked to step into a private room for a discussion.

“There was a gentleman there who introduced himself as a lawyer,” Labine said.

“He told me that if I spoke out about what was happening in the Richmond casino, and if the application failed before council, there was a very good chance Great Canadian would sue me.”

Great Canadian Gaming has not responded to repeated requests for comment on Labine’s allegations, citing a policy of not commenting on employee matters. In 2000, documents show Great Canadian Gaming said it had “initiated contact with and worked with (B.C. Lottery Corporation), RCMP and the Vancouver police since the beginning of suspected criminal activities,” which Labine had complained of when working at the company’s Richmond casino.

Labine said she was shocked after the brief discussion with a lawyer at the June 2000 town hall, and she left without making her planned remarks.

The next morning, Labine says, she was called at home.

“I had a call from the union rep, who told me that Great Canadian had offered me $18,000, but there were conditions attached,” she said.

Labine had originally sought a severance agreement with the company’s then-president Ross McLeod in January 2000, records show.

A copy of the Great Canadian Gaming severance agreement, signed by Labine on June 23, 2000, says that she was “currently on an approved leave of absence.”

She would resign on June 24, 2000, it says, and be paid $18,000 in a number of instalments. The final payment of $7,000 would come on Sept. 30, 2001.

According to the terms, Labine could not “engage in or attend any public or regulatory process concerning the company for the period ending Sept. 30.”

A clause stated that Labine could not take any actions to harm the company, and this obligation expired in September 2001.

“For the purposes of this clause, the presence of Muriel Labine, in and of itself, in the audience before Coquitlam town council on June 22, 2000 did not constitute an action which would trigger the clause,” the contract states.

“It is understood that Ms. Labine confined her remarks on that evening to advising persons she was against the casino but did not elaborate further.”

On November 6, 2000, Coquitlam council voted on Great Canadian’s casino development permit.

The councillors were deadlocked 4-4. Kingsbury, who had been elected mayor, cast the deciding vote in favour of Great Canadian’s application, records show. The casino’s business licence was approved in 2001, and the casino opened in October 2001.

Get breaking National news

“The gag order was put on me,” Labine said in an interview. “At the end, the Coquitlam casino was open.”

WATCH: Were B.C. casino staff connected to money-laundering suspects?

In an interview, Adrian Thomas, the Great Canadian Gaming vice-president who had handled Labine’s workplace complaints at the Richmond casino, says he had asked Labine to work on political campaigns in the 1990s. However, Thomas said that Labine became a troublesome employee and was driven by an agenda, and her allegations stemmed from a frustrated attempt at union organization.

Thomas left the company’s operations in 2003 and says he no longer has any connection to Great Canadian Gaming.

Review of anti-gambling policy

In an interview, Labine said she believes Great Canadian vice-president for government and media relations Jacee Schaefer — who Labine says she worked for on Kingsbury’s 1998 campaign — was an important factor in his win.

“There’s a good likelihood he wouldn’t have been elected if Jacee Schaefer wasn’t there for his election day,” Labine said.

A review of public reports shows that Kingsbury had been a strong opponent of casino development in Coquitlam as a councillor.

WATCH: Money laundering flowing through back-door channels in B.C. casinos

In 1997, the Vancouver Sun reported that Coquitlam council had rejected a casino application and that “Coun. Jon Kingsbury said he has opposed gambling as a source of revenue for amateur sports for more than a decade and won’t change his mind.”

But in 2000, Kingsbury voted to review the city’s anti-gambling policy. He cited a desire to hear from the charities that would receive funding from casino revenue, the Sun reported.

After sharply reversing his position on gambling, Kingsbury was criticized by a rival councillor, Maxine Wilson. In April 2000, the Vancouver Sun reported Wilson had alleged that “an unfair political manoeuvre by Mayor Jon Kingsbury means her bid to stop a casino proposal in its tracks won’t be debated by council until mid-May.”

In November 2002, two years after Kingsbury cast the deciding vote in favour of Great Canadian’s casino, the Vancouver Province reported that Kingsbury said the gambling expansion had been “nothing but positive” and the new casino delivered $1 million in profits to the city every three months.

Kingsbury has not responded to repeated requests for comment for this story.

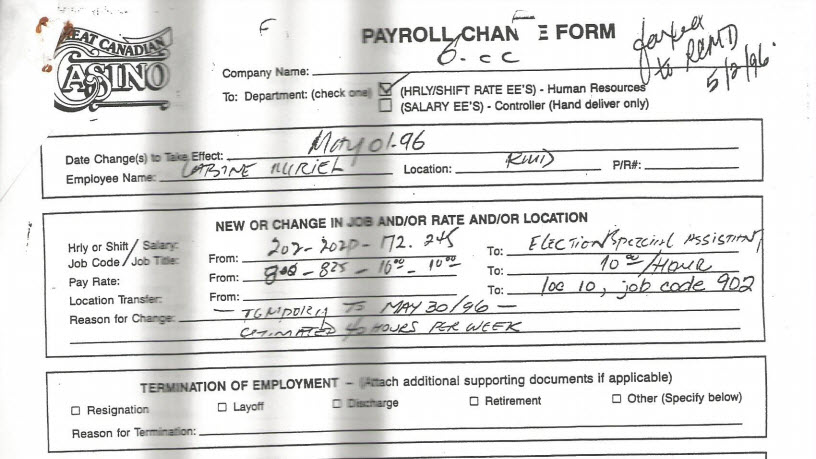

Labine says she was paid by Great Canadian to complete volunteer work on various election campaigns, mostly for Liberals. She provided documents showing her involvement in a close 1995 byelection win for B.C. Liberal MLA John van Dongen.

Labine says, in that case, she reported to Schaefer, who “ran van Dongen’s get-out-the-vote like a major general.”

‘Influence’

In a 2013 profile of Schaefer, a Globe and Mail article described her as the “godmother of gambling in B.C.” who was “renowned for her skills in organizing political campaigns, first for the Social Credit party, then for the Liberals.”

In an indication of Schaefer’s key role in Great Canadian’s gambling expansion, a 2001 report from the Richmond Review states that it was Schaefer, Great Canadian’s then vice-president, who argued that “if slot machines were put in place in Richmond, the city would see its share of the revenues skyrocket.”

Global News has not been able to reach Schaefer for comment on this story through her LinkedIn account or obtain a current contact number for Schaefer.

Labine said that in 1996, she and Schaefer worked for the B.C. Liberals.

“Great Canadian paid my wages, the Liberal party paid my expenses,” Labine said. “We worked Liberal Party campaign headquarters, we trained the ridings on how to get out the vote, and they sent me on the road to teach the campaigns how to win on election day.”

While there was nothing wrong under B.C.’s election rules about businesses or unions working on political campaigns or paying their employees to work on campaigns, Labine says she has no doubt that Great Canadian was an influential political force.

“Did they have an impact or an influence on the campaigns? Absolutely,” Labine said.

“I know that Jacee, at the very first campaign I was at for van Dongen, got off the phone after talking to Liberal headquarters and told me that she had just dictated the gaming policy for the Liberal Party.”

Labine said she doesn’t know if the alleged comment was “bravado” or not.

But Labine said in the cases of former Coquitlam mayor Kingsbury and van Dongen, she wonders if Great Canadian’s campaign assistance could raise questions of conflict of interest.

Van Dongen, for example, went on to become B.C. Liberal solicitor general. In 2008, after a CBC story alleged that cash could easily be laundered through slot machines at Great Canadian’s Grand Boulevard Casino in Coquitlam, along with another company’s casino in Burnaby, it was van Dongen’s responsibility to respond to the allegations. Van Dongen promised that B.C. Lottery Corporation would “beef up its procedures to help prevent money laundering in casinos,” CBC reported at that time.

“To me, van Dongen should never have been investigating Great Canadian,” Labine said. “Great Canadian helped him first get elected. To me that, in my mind, that was a conflict of interest.”

Global News has not been able to reach van Dongen, who left the B.C. Liberal party in 2012, for comment.

But it was not just B.C. Liberal politicians that Great Canadian supported.

Labine said that she worked on the 2011 NDP leadership campaign of Mike Farnworth, who was the NDP’s critic for gaming and involved in the party’s casino expansion policy in the late 1990s.

Farnworth is currently B.C.’s solicitor general.

Election records show that Farnworth was the candidate backed by Great Canadian in 2011, receiving a total of $7,500 donated from three different Great Canadian entities.

In an interview, Labine says she recalls Farnworth coming into a campaign meeting, beaming, with a Great Canadian cheque in hand.

She says that she warned Farnworth about her concerns with Great Canadian and urged him to return the money. And when he did not, she resigned from his campaign.

In an interview with Global News, Farnworth said that he remembers Labine working on his campaign.

“Because I received some donations from the gaming industry, she felt I shouldn’t accept them,” he recalled. “And we accepted them. so she decided she didn’t want to be part of the campaign.”

Farnworth said that in May 1997, bet limits were raised in B.C. casinos because the government wanted to increase revenues. But Farnworth did not remember much about the decision to introduce baccarat tables.

He said the issue of gangs arriving to launder money through baccarat tables was not brought to his attention in 1997. However, the concern of loan sharking was raised, Farnworth said. He said he was informed that police were aware of it and “looking out for it.”

WATCH: Were B.C. casino staff connected to money-laundering suspects?

‘I’m ashamed’

Labine says she has been haunted by her decision to take the $18,000 payout from Great Canadian and wishes she had spoken out at the Coquitlam town hall in 2000.

“I’m ashamed to say I took the money,” she said. “Through all of these years, I’ve regretted taking that money. I didn’t have the courage to step up and speak out then.”

But she is coming forward now, she said, because something has to change.

“When the stories started breaking about the fentanyl crisis, the drug crisis in our province, when stories started breaking about the housing crisis and how this money that was coming through the casinos was affecting every single British Columbian, that struck home.”

She believes the conclusion of independent reviewer Peter German — that B.C. casino operators were unwitting victims of money laundering — is false. And it was odd, she believes, that German’s review didn’t look at the period when the NDP was in power in the late 1990s.

“It went from the point when the Liberals were in charge. I have a little bit of a problem thinking that, ‘OK, we’re not going to go back that far, because we don’t want to look,’” Labine said. “The NDP were seeing revenue coming in, and they desperately needed revenue at that time. There was a big jump in casino revenue.”

Labine thinks that both the NDP and B.C. Liberals are against a public inquiry because they are “afraid to turn over the rocks and see what’s there.”

Ultimately, that is why she has come forward. For two decades, she has seen the same pattern, over and over.

“Two years from now, the media is going to be right there reporting on the same thing because the gangs will find another way right into the casinos again,” she said. “It has to be a federal inquiry.”

sam.cooper@globalnews.ca

Comments