The return of oil and gas production following the devastating Fort McMurray wildfire and a colder than usual winter pushed Canada’s national greenhouse gas emissions up in 2017 for the first time in several years, a new report says.

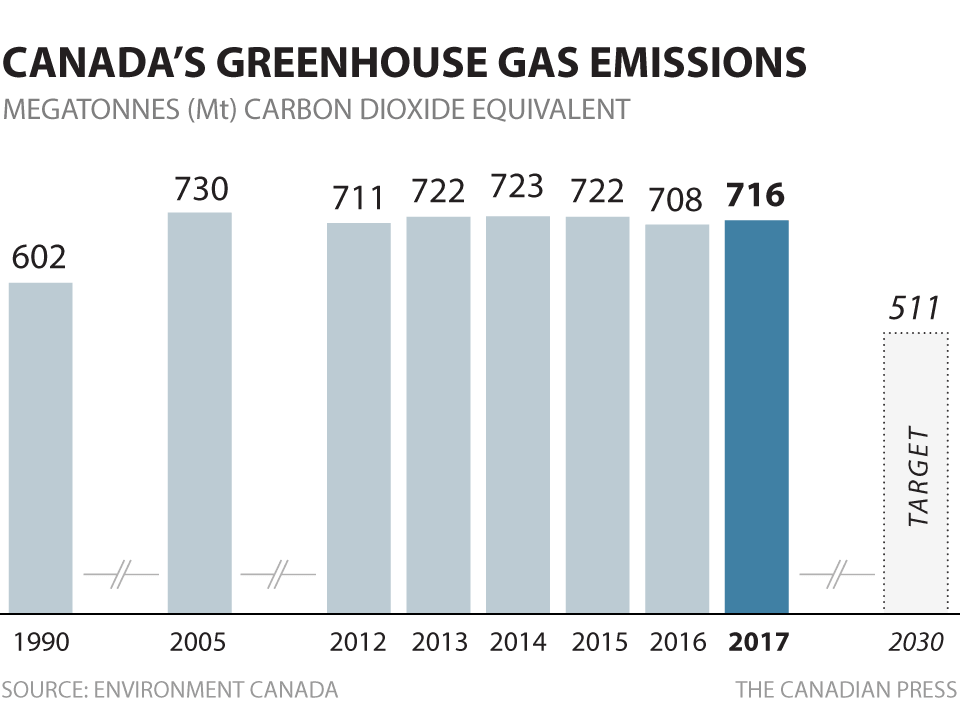

The latest national inventory report on emissions, filed this week with the United Nations climate change secretariat, showed 716 million tonnes of greenhouse gases were produced in Canada in 2017, an increase of eight million tonnes from 2016.

READ MORE: Ontario ‘alarmist’ over federal government’s powers if carbon pricing law stands, court hears

The uptick pushes Canada even further away from its Paris climate change agreement pledge to slash emissions to 70 per cent of what they were in 2005 by 2030.

Canada needs to get emissions to no more than 511 million tonnes by 2030 to meet its pledge, even though international scientists last year warned the country must have steeper reductions to prevent the impacts of a warming planet from becoming impossible to mitigate.

The report follows one released two weeks ago – made public amid a political battle over the new federal carbon tax – that said Canada is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world.

Environment Minister Catherine McKenna defended her government’s record on emissions despite the uptick. She said the government’s “strongest” measures to fight pollution hadn’t been implemented in 2017, including the carbon tax, clean fuel standards and phasing out coal power.

“Canada’s climate plan is working, and the overall trend in emissions is downward toward 2030,” she said.

The 2017 emissions are two per cent below what emissions were in 2005.

Get daily National news

Canada’s existing climate change action plan, which includes the carbon tax and subsidies to spur electric vehicle purchases, only gets Canada about 60 per cent of the way to its 2030 commitment. McKenna has previously said she thinks that gap will be closed as people adopt cleaner technology faster than expected.

On Tuesday, Environment Canada officials said the report did not analyze the direct impact of carbon pricing. Four provinces had a carbon price in 2017 – British Columbia and Alberta had a direct carbon tax, and Ontario and Quebec had cap-and-trade systems. B.C. and Alberta saw increases in emissions, while Ontario and Quebec saw a decrease.

Conservative environment critic Ed Fast said the 2017 numbers prove the Liberals’ climate plan isn’t working. The Conservatives are heavily critical of the carbon tax strategy and plan to eliminate it if elected in the fall.

“We don’t believe you can tax your way to a clean environment,” he said.

WATCH: Canada not among top countries cutting CO2 emissions

McKenna has been critical of the Conservatives for not saying yet what they would do to cut emissions, but Fast said Tuesday the Conservative plan will cut emissions and be released in plenty of time for Canadians to judge it before voting day in October.

Emissions went down from electricity generation, small vehicles and the chemical industry, but that wasn’t enough to offset the increases in larger vehicle use, residential heating thanks to the cold 2017 winter, and oil production one year after oilsands producers slashed production for two months because of the Fort McMurray fires.

Environment groups say the oilsands’ impact on Canada’s emissions cannot be overstated. Keith Stewart, a senior energy strategist at Greenpeace Canada, said emissions from the oilsands eclipse those from every province except Alberta and Saskatchewan.

In 2017, oil and gas production and refineries accounted for more than one-sixth of Canada’s total emissions. Emissions from production alone were up six million tonnes from the year before.

Stewart said as long as the Liberals try to increase oil exports, they’re not going to have much success at bringing down emissions.

“That is the dilemma at the heart of Canadian climate policy,” he said. “You can’t actually do both.”

- Attack on Iran triggers global flight disruptions, impacts Canadian travellers

- Queen’s University students stranded in Doha after Iran attack shuts down airspace

- WWE Hall of Fame ring belonging to wrestling legend recovered after stolen

- Quebec politician praised for speaking openly about menopause symptom in legislature

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.