In the golden age of rail travel, taking the train in Canada was a different experience than what many are used to today.

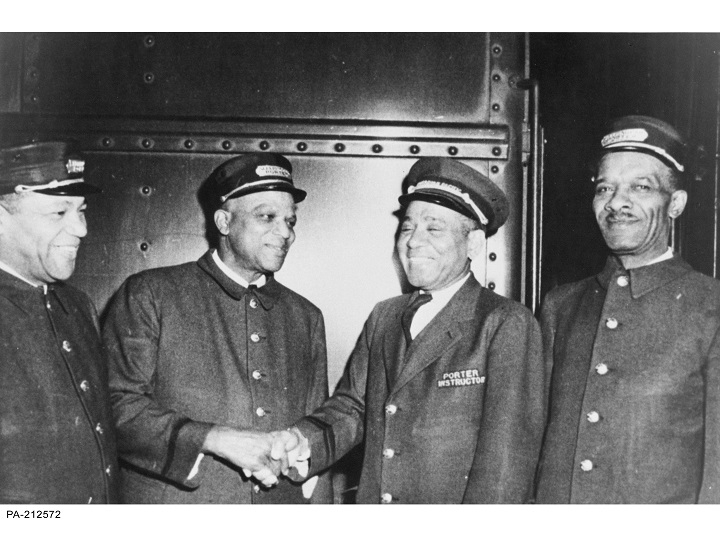

For one, passengers of the 20th century were met by porters, who shined their shoes, carried their luggage, looked after ladies’ handbags, and overall catered to passengers’ every whim.

Also, these servicemen were almost all black. Workplace segregation policies meant that a train porter was the only job a black man could get at the time.

“Their families relied heavily on these jobs, because this was at a time when the only jobs that were available to black people in this country were as sleeping car porters,” says Cecil Foster, author of the new book They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada.

“It was a job that often came with little or no wages, so they had to rely on tipping, and if they didn’t get tips, they would not be able to feed their families,” said Foster.

It was also a job that erased their names, as Foster indicates in the title of his book. Black porters were often indiscriminately called “George’s boys” and then, eventually, just “George.”

Both monikers refer to the man who started the sleeping porter car service — 19th century American engineer and industrialist George Pullman. Pullman marketed and popularized a train travel experience in which white passengers could imagine they were inside a southern plantation house, served by black servants.

Get breaking National news

In fact, some of the first porters in Canada, Cecil explains, were ex-slaves.

Travelling across the country and through different time zones, these “sleepy porters,” as they called themselves, worked 18-24 hour days, Foster says.

When they did get a chance to eat, it was separate from passengers, cordoned off by a black veil that divided the dining car.

Then there was the threat that constantly loomed over each porter: even the smallest offence could get them fired.

“Just about everything about their lives when they were on the train was regulated,” said Foster. “The fact that they might spill a bit of coffee on someone, and by the time they got back into the station, a report may be made and they would be fired — it meant that they had to be fighting for recognition as human beings.”

But despite being trapped in grueling jobs marked by racist treatment, the porters managed to unite to form a union. In 1954, in what Foster calls a “threshold-crossing moment,” a Toronto delegation of porters boarded a train to Ottawa to meet with members of the federal cabinet. Their goal? To transform Canada.

“They said to the government, ‘look your policies are just bad’,” says Foster. ” ‘You cannot have Canada as a white man’s country. You cannot have an immigration policy that does not allow black people or people from…wherever into this country—you have to really get a policy…based on their merit, based on their ability to add to this country.’ ”

Change, Foster admits, did not happen right away as the government was dismissive of their demands at first.

By the late 1960s and into the early 70s, however, the activism of the black train porters began to bring about some victories. In 1971, under Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Canada’s immigration policy shifted to one “based on merit, the same system that we have in place today,” Foster says.

Foster acknowledges that the story of the black train porters seems tucked away in a chapter of Canadian history that most Canadians know little about. He blames “the script” for that.

“But these men in the 1950s were challenging Canada to become a country where any human being could live up to his or her human dignity and to achieve it through whatever form of work they chose…the result is the Canada that we see walking these halls and the streets today — a Canada that is multiracial and multicultural.”

%20STILL.jpg?w=1040&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.