Black mould has built up in Cat Lake First Nation homes in northwestern Ontario to the point where children and elders are facing sicknesses, and the community has declared a state of emergency.

READ MORE: ‘We’re not bluffing’ — Ontario First Nation urges Trudeau, O’Regan to witness housing crisis

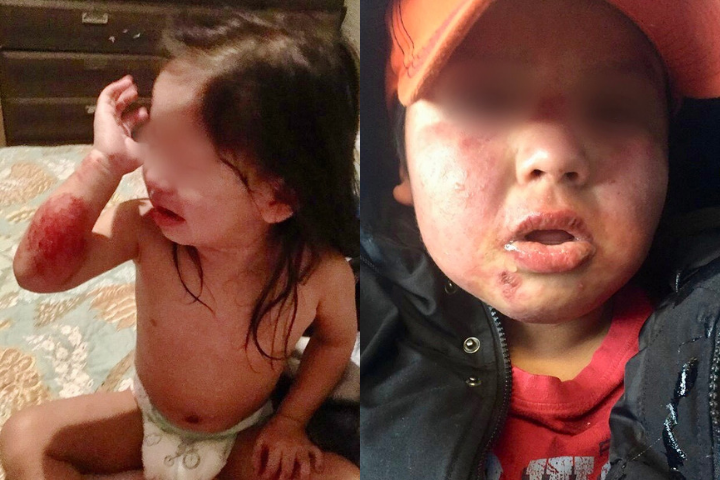

The mould buildup is just the beginning of the problem, according to officials in the community. The housing problem extends into a health crisis, and the photos of children covered in red rashes are proof.

The First Nation of about 700 people declared a state of emergency last month citing “profoundly poor conditions of housing,” as the cause of a public-health crisis, which has led to invasive bacterial disease, including lung infections.

WATCH: Cat Lake officials say issue is about mould, not the winter road

In an interview with Global News, Derek Spence, the head councillor at the Cat Lake Band Office, explained seeking medical treatment for those sickened by the mould is an added struggle.

The community has one nursing station, three nurses and zero permanent doctors.

“You go to the clinic and that’s all you get. There’s nobody else you can go to if you think you’re being misdiagnosed,” he said, noting the example of one child whose rashes were mistreated at first.

“He had an infection and they couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him. We later learned he was given the wrong antibiotics,” he added.

Get weekly health news

Spence explained the doctors come to visit for one week each month, but only those who have referrals from nurses get appointments.

“Sometimes we’ll have maybe 100 people in line waiting to see the doctor and maybe she’ll probably see maybe 40 so the other 60 are waiting until the next visit.”

Angela Mashford-Pringle, who works at the Waakebiness-Bryce Institute for Indigenous Health at the University of Toronto, explained to Global News that there are several other problems in accessing health care in remote areas.

READ MORE: Band councils, hereditary chiefs — here’s what to know about Indigenous governance

Indigenous communities such as Cat Lake often don’t have 24-hour health services, or any sort of hospital nearby, she explained.

“A lot of them don’t have a doctor,” she noted.

“They have doctors who fly in for a few days or a week every month or every two months, but they don’t have doctors every day.”

That’s why medical emergencies often aren’t dealt with in the most effective way.

In the case of a medical emergency, Mashford-Pringle explained: “You would hope that you could get a hold of the nurse, and can explain it well enough to them.”

WATCH: PM accused of disconnect after refusing to call Cat Lake a ‘national disgrace’

The nurse would then consult a doctor, who may be cities away. If transport to a hospital is needed, Mashford-Pringle explained it would likely be an airlift.

In Cat Lake, for example, Spence explained airlifts for serious cases are typically to Winnipeg or Toronto.

Beyond emergencies, Mashford-Pringle noted that routine exams aren’t possible within the communities because there is no equipment.

“Most communities don’t have an X-ray machine, nebulizer or ultrasound machine,” she said. “Even if it’s something that could easily get resolved, it means they have to come out of the community to get tests done.”

Or, the equipment is flown in, which could also take days.

Beyond physical health, gaps in mental-health care for Indigenous communities were reported during the Attawapiskat crisis in 2016.

READ MORE: 1 year after suicide crisis, Attawapiskat still lacking mental health resources

Attawapiskat, a small Indigenous community in northern Ontario, declared a state of emergency following a spike in suicide attempts.

The Cree community of about 2,000 people saw nearly a dozen suicide attempts in a single Saturday night in April 2016, including one involving an 11-year-old, and more than 100 in the previous seven months.

In 2017, a year after the crisis was declared, Attawapiskat residents still didn’t have access to permanent mental-health workers due to housing issues.

Government response for Cat Lake

Spence and other community representatives have been calling on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Indigenous Services Minister Seamus O’Regan to visit the community to see the conditions firsthand.

Amid mounting pressure, O’Regan announced late last week that he would visit the community. In an email to Global News, the minister’s office said the exact date is not yet confirmed.

READ MORE: Trudeau wants new relationship with Indigenous people to be his legacy as PM

The minister will first meet in Thunder Bay with Cat Lake’s chief on the request of Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde.

O’Regan spoke to the chief of Cat Lake First Nation on Friday. The two agreed on a plan that includes speeding up the delivery of materials for housing repairs, a seven-unit housing complex, and for new construction.

WATCH: We can’t decide ‘right solution’ for First Nations people, Trudeau says

He also said his department will support an independent community medical assessment of health issues, if the chief and council wish to have one.

Ongoing repairs to the local nursing station will also be expedited, and completed by March 31.

Indigenous Services Canada has committed nearly $1.7 million to Cat Lake between 2018 and 2019 for health programming.

— With files from Global News reporter Andrew Russell, The Canadian Press

Comments