Thanks to the evolution of smartphones, methods of collecting data and tracking populations in nature have come a long way.

Previous methods included aerial or physical surveys with pencils, notepads and sketches. Now, the same information can be gathered and curated by anyone, using a device that most carry around in their pocket.

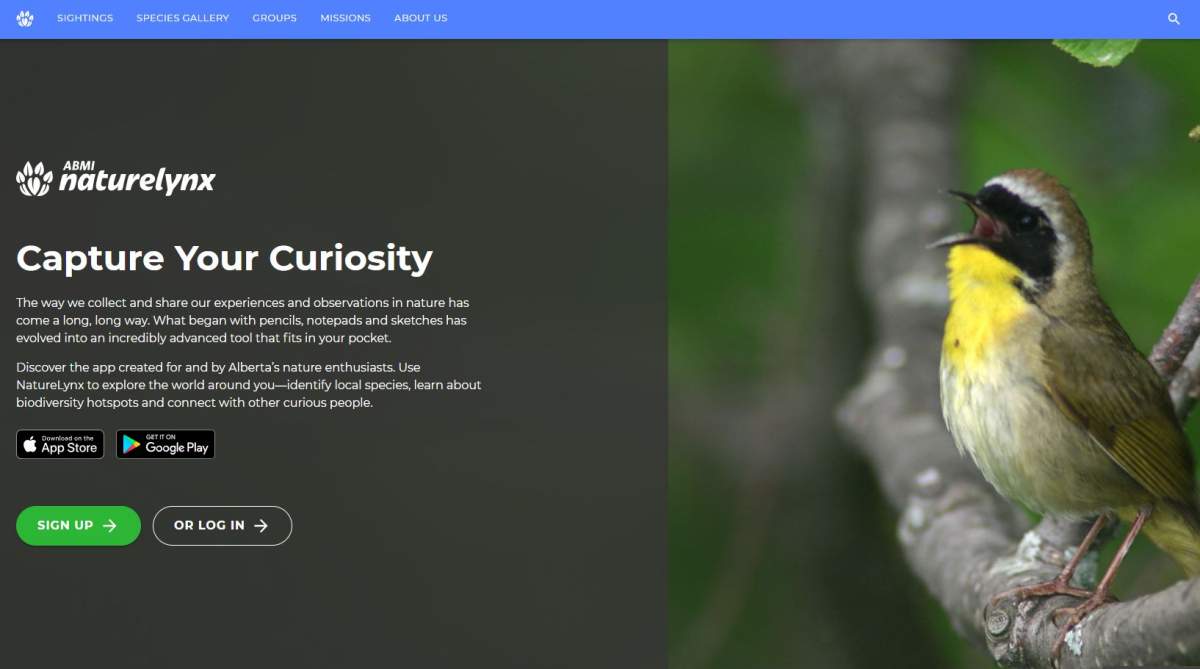

The Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI) created a free, public app called NatureLynx to get Albertans outdoors and participating in baseline population studies.

“As an organization, we monitor species and habitats across the whole province of Alberta,” Jordan Bell, the ABMI’s citizen science coordinator said.

“We saw an opportunity to sort of leverage our expertise in managing this provincial monitoring program and also provide an opportunity to learn about Alberta’s natural heritage and living resources.”

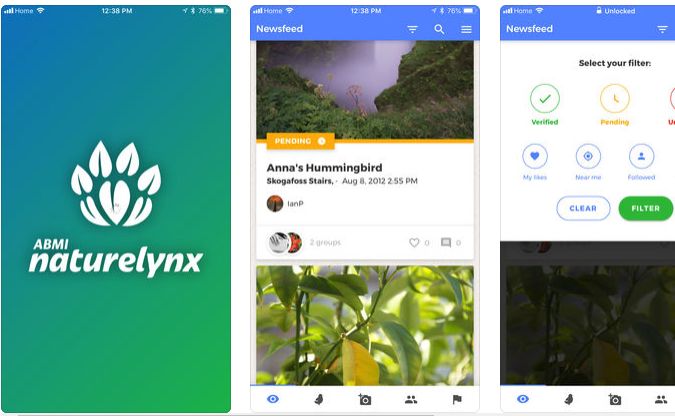

NatureLynx launched in July. It helps users explore the outside world, identify local species, learn about biodiversity hot spots and connect with others.

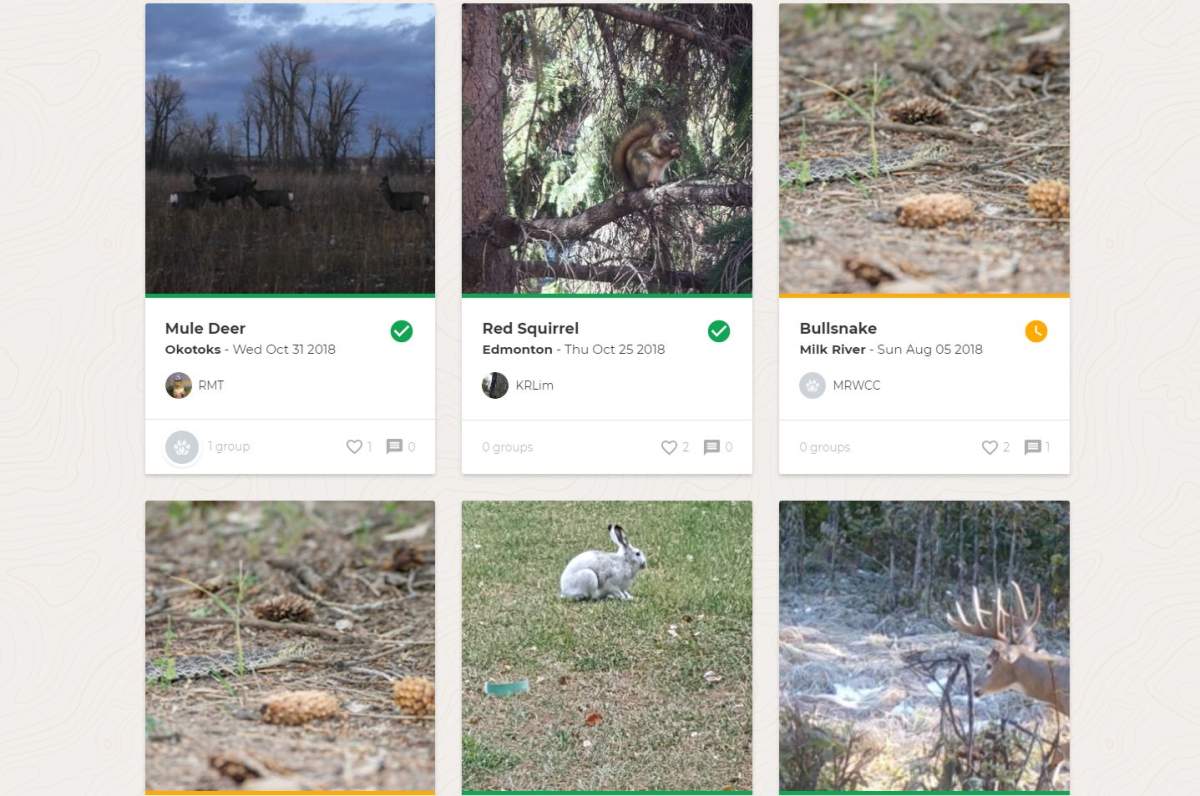

Since participants use their smartphone, they input a photo of the subject matter, and a time and GPS location can also be included.

“I see citizen science being beneficial certainly by having more people out in our environment collecting information — we’re definitely increasing the reach of our ability to monitor landscapes — but it also has a secondary benefit of allowing people to get more involved in the scientific process, learn a little bit more about how data is actually collected… and then also to provide greater access to data, both for scientists and the public.

Get daily National news

“That’s really where citizen science takes off,” Bell said.

It’s been used my municipalities, provincial wildlife groups, even individuals just interested in a certain phenomenon or monitoring population trends and changes.

It’s been used to count urban deer in Okotoks, hares across the province, even different species of trees.

“Citizen science is a growing field and over time has received greater recognition for the value that the public can actually provide,” Bell said.

Smartphones, apps and inviting civilians to take part are relatively new methods. Other methods used in the field previously include aerial surveys with helicopters, wildlife cameras, radial collars, audio recordings and geo-spacial analysis.

Advancements in technology provide more options for scientists.

“It’s really increased our ability to gather more data and sort of passively monitor the collective environment,” Bell said.

Plus, this type of crowd sourcing also encourages community engagement with the environment.

“There has been a lot of interest from place-based organizations or groups that have specific questions about their community,” Bell said. “A huge benefit of the NatureLynx application is now we’re providing a tool for people to actually run their own projects and kind of answer their own questions.

“Questions like monitoring urban wildlife or human-wildlife conflicts… trying to get a better understanding of what is actually within our communities and trying to inform future management decisions off the data that they can collect.”

It can help researchers get a better understanding about the number of animals, migration patterns, population changes, appearance changes, urban interactions, and even how they’re adapting to climate change.

“We’ll hopefully be able to compare that to the data that we’re collecting across the province,” Bell said. “We do monitor at a regional scale but as we can get more information about local areas, it’ll allow us to be able to get a better understanding of those broader scale trends over time.”

Comments