When she was nine, Stacey Gorlicky became obsessed with how she looked.

She would look at other people eating a slice of pizza and think, “Why can they eat pizza and cake and carbs and keep weight off?”

To ease her concerns, which only grew when she became a teenager, she started yo-yo dieting.

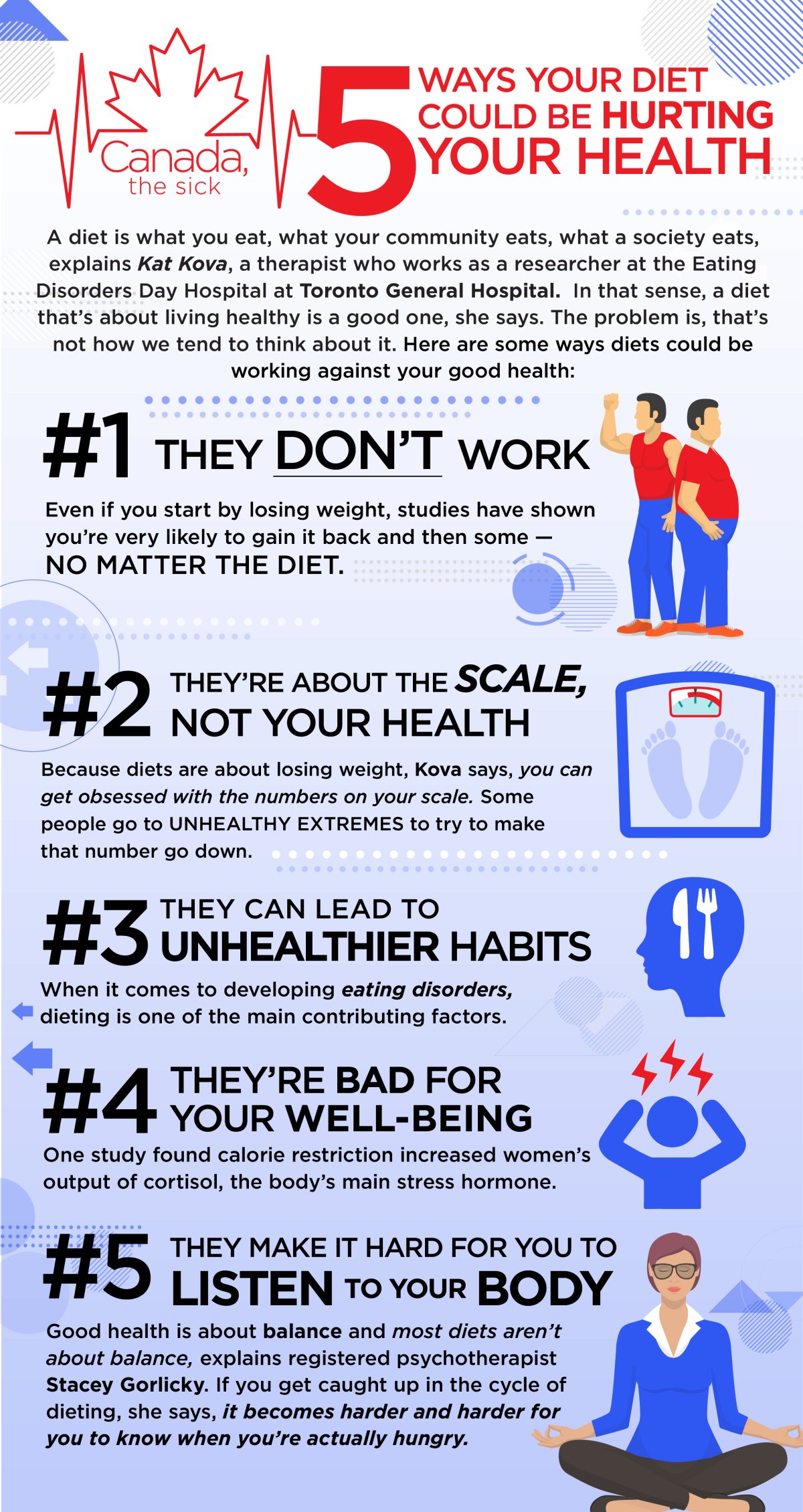

It’s easy to get caught looking for the next quick fix, she says. She exercised, tried a new diet, over-exercised, then over-ate and binged, then over-ate and binged again. It got to the point where Gorlicky, whose eating disorder propelled her into her current career as a registered psychotherapist specializing in treating addiction, could no longer tell when she was hungry.

She was in pursuit of a flat belly and “nothing was working for me.”

In hindsight, Gorlicky can trace how easy it was for a need to be skinny to override a desire to be healthy. It’s a quick slide, but recovering from an eating disorder isn’t. Gorlicky has been in recovery for 12 years now.

“It’s really about trying to get the psychological aspect under control,” she says. It’s an eating disorder, Gorlicky explains, but it infects your brain, skewing your sense of self, hindering your well-being and your happiness.

“It took years.”

At a time when there’s never been more information about how to live a healthy lifestyle, Canadian obesity rates are twice as high as they were in the 1970s and Canadians are also increasingly suffering from chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes. With its Canada the Sick series, Global News is looking at what’s going on, and why knowledge isn’t enough.

WATCH: Canada’s chief public health officer explains what contributes to Canada’s high obesity rate

The unavoidable reality is that our world isn’t designed to make it easy to be healthy, experts say, and diets aren’t the quick fix they’re portrayed as.

“People don’t go to sleep at night wanting to make unhealthy choices and hoping to gain weight,” says Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, author of The Diet Fix and founder of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nutrition and weight management centre.

“It’s just this constant barrage of nutritional chaff … nobody stands a chance in that environment unless they have very fortunate genes or live very different lives than what are now considered to be normal.”

Normal is a processed food industry that isn’t invested in healthy eating, says Dr. Vera Tarman, an addictions medical expert and author of Food Junkies: The Truth About Food Addiction. It’s a world where hyper-palatable foods with addictive ingredients like sugar and flour are in easy, often affordable reach.

The solution we keep grasping at is diet, Tarman says. That’s reflected in the numbers.

WATCH: How to survive on a vegan diet

Weight loss is a multibillion-dollar industry, per 2017 figures from market research company IBISWorld. That same year, a nationwide poll from Insights West found that nearly half of Canadians had tried a diet sometime the year prior in a specific bid to lose weight.

An Ipsos poll conducted for Global News last month yielded similar results.

- B.C. to ban drug use in all public places in major overhaul of decriminalization

- 3 women diagnosed with HIV after ‘vampire facials’ at unlicensed U.S. spa

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

- ‘Super lice’ are becoming more resistant to chemical shampoos. What to use instead

Forty per cent of those surveyed said they followed a particular diet. Calorie counting topped the list, followed by a vegetarian diet, Weight Watchers, some form of cleanse or detox, and the low-carb, high-fat Keto diet. Women and young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 were more likely to have tried multiple diets.

The problem, Tarman says, is that dieting is not a solution for good health.

“Diets are not sustainable, healthy lifestyles,” she says. “It’s kind of like a diet is a Band-Aid to a bad living environment.”

Diets aren’t inherently unhealthy, explains Kat Kova, a therapist at KMA Therapy who also works as a researcher at the Eating Disorders Day Hospital at Toronto General Hospital. The problem is the general public has largely twisted them into a tool for weight loss — the results of which can be unhealthy.

“Many people will use their scale to measure their progress toward their goal when they’re dieting,” Kova says. “But that can lead to an obsession with and a frustration with the numbers as they go up and down.”

Freedhoff thinks a huge part of the problem is our simplistic approach to dieting.

“I think we need to step back,” he says. It’s not helpful to ask, why are there more people with obesity despite knowing all that we do about healthy living, Freedhoff says, nor is it helpful to ask if the solution is, do we just quit dieting?

“Suggesting that all diets are problematic and don’t help is problematic and doesn’t help,” he says, although he acknowledges “dieting is broken in the context of the belief out there that you need to suffer in perpetuity if you want to succeed.”

Too often you won’t succeed, says Mary Bamford, a registered dietitian with Renascent in Toronto, because you’re just cycling between diets in search of a weight management fix.

“People are going on these diets without actual evidence-based facts on how effective they are,” she says. “There ends up being, if it doesn’t work out, a lot of self-blame and self-shame.”

It’s a result of our culture, Bamford says, a response that’s fairly unique to excess or perceived excess weight.

“If someone has high blood pressure and they’re given a treatment plan and medication and their blood pressure is still high, they don’t ‘say shame on me.’”

Given that a lot of people won’t keep all the weight off, that’s a lot of shame.

Some studies have shown that just 20 per cent of people are able to maintain their weight loss after one full year, while others show that most people will regain more than two-thirds of the weight they lost within two years of losing it.

So if you want to diet for health — not just weight — reasons, is there a way to do it right?

You can start by throwing out the idea that if you try hard enough you’ll achieve your goal, Freedhoff says.

“The food environment pushes people towards low-quality food with high calories,” he says. “This idea that simply wanting it badly enough will allow a swimmer to forevermore swim tirelessly against a very strong current is flawed.”

Then, make peace with your weight.

“The results that people want are the results they’re told they’re supposed to have,” Freedhoff says. But in actuality, you don’t need to have lost precisely 40 pounds to be healthy. If you’re doing it for health reasons, he says, even 10, 20 or 30 pounds can be beneficial.

Still, Freedhoff says, the bigger picture fix will likely have to come through legislation. Namely, taxes on sugary drinks, curtailment of advertising to kids, zoning to prevent fast food near schools, some clearer, junk-free warning labels.

But you can start your individual fix with a multidisciplinary approach, Bamford says.

Talk to your doctor about finding the best evidence-based diet for you and make sure there is an expert there who can help you change your mindset as well so you’re not focusing heavily on the scale and the shame it can carry.

“It’s very personal,” she says. It’s about figuring out “what’s the best food pattern that works for you as an individual.”

And then? Slow down.

WATCH: Organization the key to healthy eating

Food isn’t just for your body, Gorlicky says, it’s for your mind too.

Pick foods that will fill you up, she says. It’s not about how many calories but about their nutritional value. Then, eat slowly and focus on your food. No mindlessly shoving a spoon into your mouth while you binge-watch a TV show, no eating to cope with loneliness or exhaustion.

“Food is really like anything you’re going to use and abuse,” Gorlicky says. “You have to have balance.”

— with a file from Leslie Young

Exclusive Global News Ipsos polls are protected by copyright. The information and/or data may only be rebroadcast or republished with full and proper credit and attribution to “Global News Ipsos.”

This Ipsos poll on behalf of Global News was an online survey of 1,001 Canadians conducted between Aug. 20-23. The results were weighted to better reflect the composition of the adult Canadian population, according to census data. The precision of Ipsos online polls is measured using a credibility interval. In this case, the poll is considered accurate to within plus or minus 3.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Comments