WARNING: Images in this story contain graphic content.

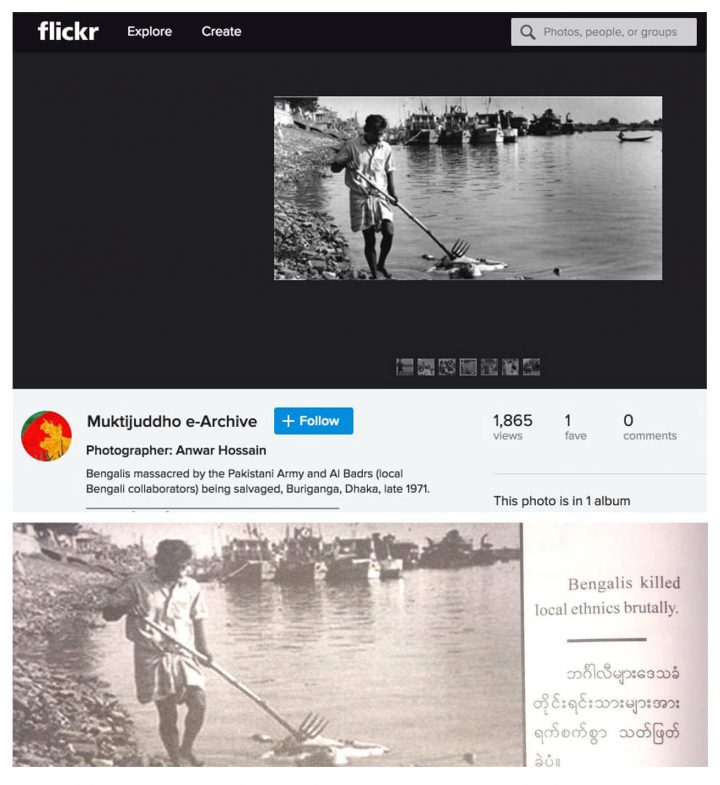

The grainy black-and-white photo, printed in a new book on the Rohingya crisis authored by Myanmar‘s army, shows a man standing over two bodies, wielding a farming tool. “Bengalis killed local ethnics brutally,” reads the caption.

The photo appears in a section of the book covering ethnic riots in Myanmar in the 1940s. The text says the image shows Buddhists murdered by Rohingya – members of a Muslim minority the book refers to as “Bengalis” to imply they are illegal immigrants.

But a Reuters examination of the photograph shows it was actually taken during Bangladesh‘s 1971 independence war, when hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshis were killed by Pakistani troops.

It is one of three images that appear in the book, published in July by the army’s department of public relations and psychological warfare, that have been misrepresented as archival pictures from the western state of Rakhine.

In fact, Reuters found that two of the photos originally were taken in Bangladesh and Tanzania. A third was falsely labeled as depicting Rohingya entering Myanmar from Bangladesh, when in reality it showed migrants leaving the country.

WATCH BELOW: What life is like inside a Rohingya refugee camp

Government spokesman Zaw Htay and a military spokesman could not be reached for comment on the authenticity of the images. U Myo Myint Maung, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Information, declined to comment, saying he had not read the book.

Get daily National news

The 117-page “Myanmar Politics and the Tatmadaw: Part I” relates the army’s narrative of August last year, when some 700,000 Rohingya fled Rakhine to Bangladesh, according to United Nations agencies, triggering reports of mass killings, rape, and arson. Tatmadaw is the official name of Myanmar‘s military.

Much of the content is sourced to the military’s “True News” information unit, which since the start of the crisis has distributed news giving the army’s perspective, mostly via Facebook.

The book is on sale at bookstores across the commercial capital of Yangon. A member of staff at Innwa, one of the biggest bookshops in the city, said the 50 copies the store ordered had sold out, but there was no plan to order more. “Not many people came looking for it,” said the bookseller, who declined to be named.

On Monday, Facebook banned the army chief and other military officials accused of using the platform to “inflame ethnic and religious tensions.” The same day, UN investigators accused Senior General Min Aung Hlaing of overseeing a campaign with “genocidal intent” and recommended he and other senior officials be prosecuted for crimes against humanity.

In its new book, the military denies the allegations of abuses, blaming the violence on “Bengali terrorists” it says were intent on carving out a Rohingya state named “Arkistan.”

Attacks by Rohingya militants calling themselves the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army preceded the military’s crackdown in August 2017 in Rakhine state, in which the UN investigators say 10,000 people may have been killed. The group denies it has separatist aims.

The book also seeks to trace the history of the Rohingya – who regard themselves as native to western Myanmar – casting them as interlopers from Bangladesh.

WATCH BELOW: Could the world have done more to stop the Rohingya crisis?

In the introduction to the book the writer, listed as Lieutenant Colonel Kyaw Kyaw Oo, says the text was compiled using “documentary photos” with the aim of “revealing the history of Bengalis.”

“It can be found that whenever a political change or an ethnic armed conflict occurred in Myanmar those Bengalis take it as an opportunity,” the book reads, arguing that Muslims took advantage of the uncertainty of Myanmar‘s nascent democratic transition to ignite “religious clashes.”

Reuters was unable to contact Kyaw Kyaw Oo for comment.

Reuters examined some of the photographs using Google Reverse Image Search and TinEye, tools commonly used by news organizations and others to identify images that have previously appeared online. Checks were then made with the previously credited publishers to establish the origins of those images.

Of the 80 images in the book, most were recent pictures of army chief Min Aung Hlaing meeting foreign dignitaries or local officials visiting Rakhine. Several were screengrabs from videos posted by Rohingya militant group the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army.

Of eight photos presented as historical images, Reuters found the provenance of three to be faked and was unable to determine the provenance of the five others.

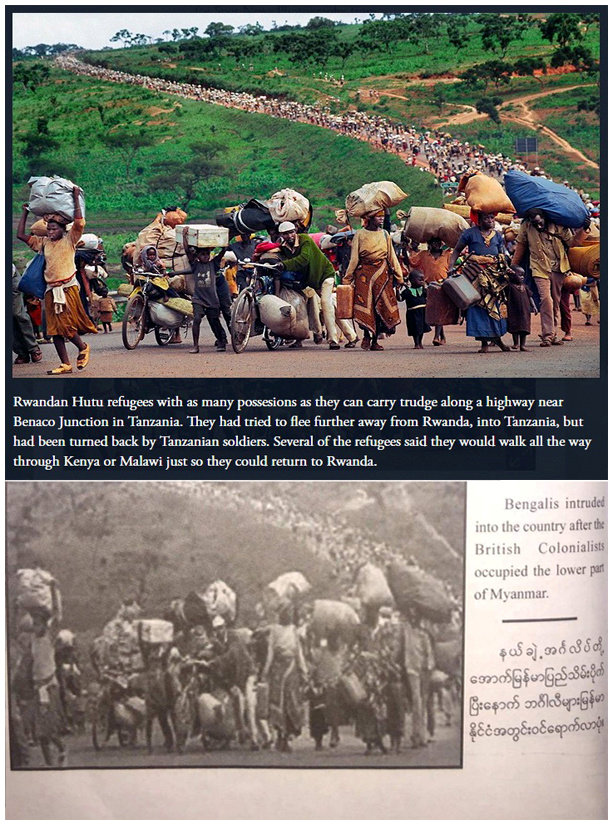

One faded black-and-white image shows a crowd of men who appear to be on a long march with their backs bent over. “Bengalis intruded into the country after the British Colonialism occupied the lower part of Myanmar,” the caption reads.

The photo is apparently intended to depict Rohingya arriving in Myanmar during the colonial era, which ended in 1948. Reuters determined the picture is in fact a distorted version of a color image taken in 1996 of refugees fleeing the genocide in Rwanda. The photographer, Martha Rial, working for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, won the Pulitzer Prize. The newspaper did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the use of its photo.

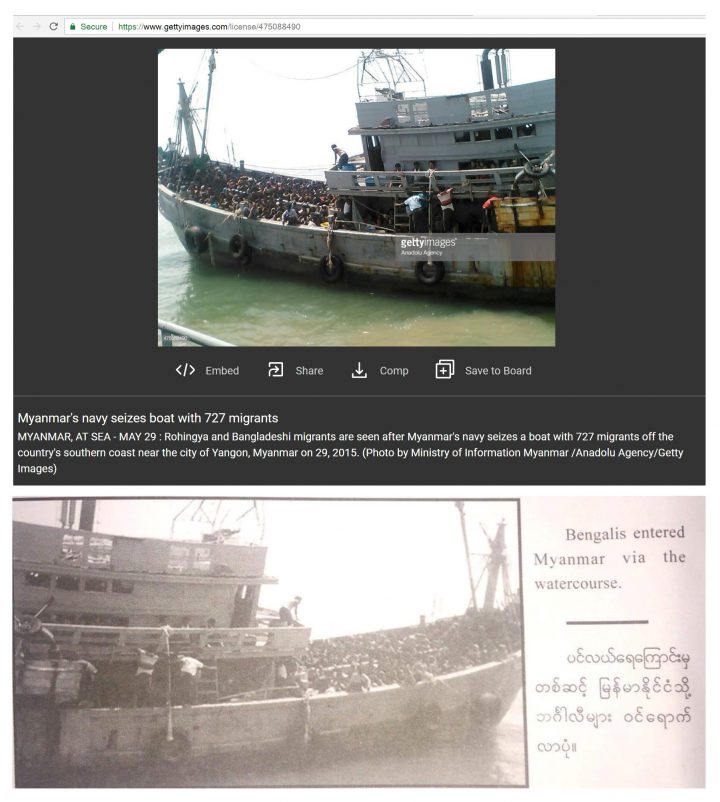

Another picture, also printed in black-and-white, shows men aboard a rickety boat. “Bengalis entered Myanmar via the watercourse,” the caption reads.

Actually, the original photo depicts Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants leaving Myanmar in 2015, when tens of thousands fled for Thailand and Malaysia. The original has been rotated and blurred so the photo looks granular. It was sourced fromMyanmar‘s own Ministry of Information.

Comments