Experts describe it as the so-called invisible disorder because in many cases you wouldn’t know someone had it.

Recently, we’ve seen a number of offenders going before the courts with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) for unspeakable crimes.

In the last year, offenders in three high-profile cases in the province have been sentenced for heinous crimes involving vulnerable victims.

Leslie Black received 16 years in prison after he lit a homeless woman on fire and left her for dead. The burns she sustained were so severe she was left partially blind and both her legs needed to be amputated.

READ MORE: Attack survivor Marlene Bird dies at 50

Jacqueline Henderson was sentenced to life in prison with no parole eligibility for seven years after beating a stranger’s six-week-old baby to death.

Last week, Jared Charles was given eight years behind bars for kidnapped and sexually assaulted an eight-year-old girl then leaving her in a wooded area to fend for herself.

All three have done the unthinkable, and their defence counsel told courts they experienced severe childhood trauma and were suspected to have FASD, or were officially diagnosed with the disorder.

Get weekly health news

WATCH: FASD advocate brings message to Calgary

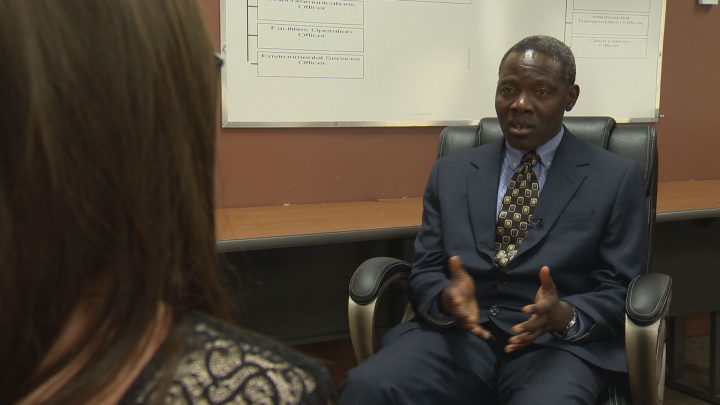

“If your executive function is affected, it means you can’t plan when you’re supposed to be attending court or going to school,” said Dr. Mansfield Mela, a forensic psychiatrist with the University of Saskatchewan. “You’re not able to prevent yourself from doing something in the spur of the moment.”

In Jared Charles’s case, the judge put forth the recommendations that he serve out his sentence at the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC) and receive treatment specially from Mela for FASD.

The biggest question on a lot of people’s minds is what treatment for convicted offenders with FASD actually looks like.

Coupled with case management and therapy for trauma, instability and bad role modelling to reduce the person’s risk.

According to Mela, whatever has happened in the offender’s life is not an excuse for what they’ve done, but provides answers on ways they can be helped.

He said it’s also believed more than 90 per cent of people with FASD will have an additional mental disorder by their teens or adulthood.

“Up to 60 per cent will be manifesting an additional alcohol and substance use disorder,” he added.

Mela, who consults at RPC and is the co-lead for diagnostic research for the Canada Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Research Network, said there are more victims of crimes with FASD than perpetrators.

“Research has shown more than 99 per cent of those who have FASD have not had any trouble with the law.”

An estimated 1.4 million Canadians have the disorder, according to Mela, and of that number only 4,000 enter the criminal justice system — a small fraction of society, but they are over-represented in prison. Ten to 30 per cent all those incarcerated have FASD.

“If you can diagnose individuals before the age of seven, their trajectories are completely different and they will live a prosocial life thereafter.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.