Having said in June that censoring an ad for a Montreal group’s panel discussion on marijuana was a mistake, Facebook then proceeded to censor it all over again in July.

And Facebook also censored an ad the group had bought that linked to a Global News story on the original censorship.

“I was a little flabbergasted by it,” says McGill University Ph.D. student Shawn McGuirk, one of the event’s organizers.

Here’s how things unfolded:

On June 26, McGuirk tried to buy a Facebook ad promoting a panel discussion on marijuana legalization scheduled for July 9 organized by the Science and Policy Exchange. It took him five hours to come up with an ad that Facebook would agree to publish — version after version was rejected for “promoting illegal drugs.” The final version, which was published, didn’t use the word “cannabis,” have a picture of a marijuana leaf or link to the original Facebook event.

On June 29, Global News published a story about the issue. A Facebook spokesperson said at the time that the platform had made a mistake:

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

“This ad does not violate our ad policies. We apologize for the error,” a spokesperson wrote. “We do allow marijuana advocacy content as long as it is not promoting the sale of the drug.”

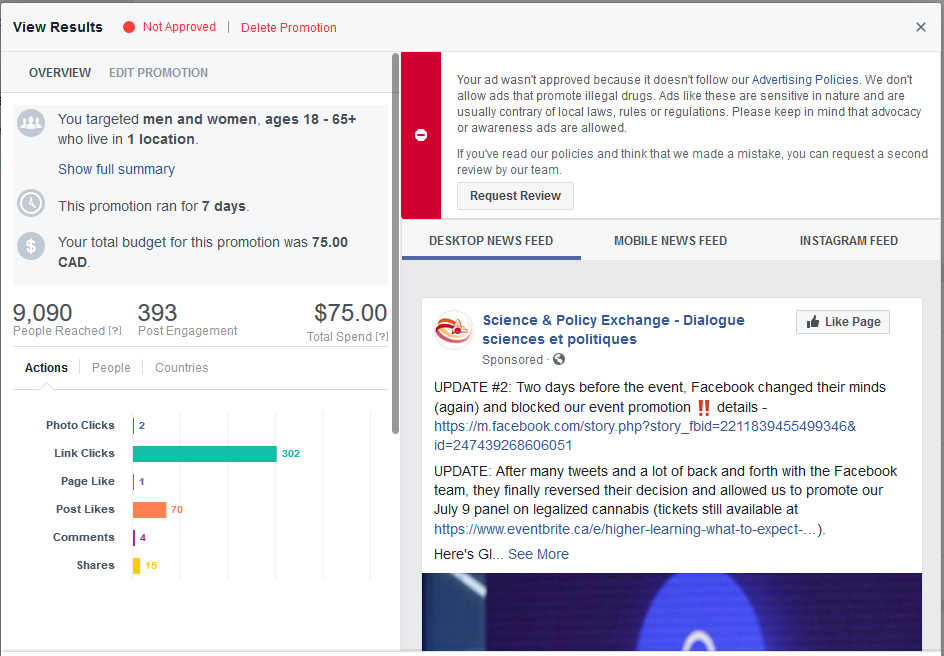

That seemed to settle the matter. But on July 7, when McGuirk tried to promote the event again, his ad was once more rejected.

“The same message as before popped up, saying, ‘This ad is now rejected because it promotes illegal drugs,'” McGuirk says. “There was still a button to appeal, so I resent them the article that Global wrote that had the quote from somebody at Facebook in it, and they replied saying that their position hasn’t changed, that they still consider that this doesn’t follow their policies, and we should change our ad if we wanted to continue.”

Here’s what that exchange looked like:

On July 10, after the panel had come and gone, Facebook rejected an ad the group had bought — and which was initially approved — linking to Global’s story:

“The ad that we had promoted that was specifically with (Global’s) article after the ad ended and after the event itself ended,” McGuirk says. “Six hours after the event ended, they sent us a message saying they were disapproving the ad, even though it had already completed, which is kind of an odd thing to do.”

“This ad was mistakenly disapproved and we apologize for the error,” a Facebook spokesperson wrote in an e-mail. “We do allow marijuana advocacy content as long as it is not promoting the use or sale of the drug.”

A student group organizing an event with an author last fall gave up on trying to buy a Facebook ad to promote it after it was repeatedly rejected as “promoting drug use,” an organizer says.

Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy was hosting Susan Boyd, who recently published a history of drug prohibition in Canada, at the University of Toronto.

“It was a last-minute event, which meant that it was really important to have people there,” explains board member Dessy Pavlova. “(The ad) was approved and disapproved maybe five times. We had a week ahead of the event to plan for it, so we didn’t manage to get it up at all.”

“I get that they’re trying to limit illegal behavior, but there has to be a way to differentiate education from selling drugs.”

Asked why marijuana-related ads were refused so consistently, if Facebook policy allows them, a spokesperson for the platform would not respond for the record.

Facebook’s restrictions also raise questions about how, or if, government cannabis retailers can use the platform.

Documents released to Global News under access-to-information laws show that Ontario’s cannabis retailer expects Facebook to restrict what it can do with a planned Facebook page.

“I reached out to our Facebook contact and he informed me that there will be issues with having product advertising on Facebook and Instagram, as it contravenes the Facebook usage policy (even though it will be decriminalized Facebook does not allow the promotion of drugs,” an LCBO official wrote in an e-mail in February.

The Liquor Control Board of Ontario refused to answer questions about the Ontario Cannabis Store’s social media presence.

(The LCBO’s Facebook page, which has 210,000 followers, is used extensively to promote various forms of alcohol.)

Of Canada’s government cannabis retailers, only Quebec’s appears to have a Facebook page.

For now, McGuirk is puzzled about how to advertise a panel planned for August on opioids.

“Right now, we’re facing a bit of a wall in how we’re going to be promoting this, to make sure that it doesn’t get flagged.”

Comments