Fifty-five years ago today, on March 25, 1958, the infamous Avro Arrow made its very first test flight.

The plane was the crown jewel of Canadian aircraft manufacturer A.V. Roe Canada, better known as Avro, then the third-largest company in Canada. The hypersonic fighter was on the cutting edge of aerospace technology at the time: it could reach a speed nearly three times the speed of sound, travelling at an altitude of 60,000 feet.

The first flight of the Arrow should have been a crowning moment for the Canadian aerospace industry. Yet the plane was scrapped by the federal government just a few months later, in a decision that remains controversial to this day.

For many Canadians, the Avro Arrow has come to symbolize both the potential, and the unfulfilled promise, of Canadian innovation.

“The Arrow represents a period when Canada stood up on its own and did its own thing,” Paul Squires, a historian with the Canadian Aeronautical Preservation Association, told Global News. “In many ways, it’s become a symbol of the country.”

“At the time, we were in the top three of the largest producers of aeronautical parts in the world. But the cancellation of the Arrow absolutely devastated the Canadian aerospace industry.”

When it comes to the Avro Arrow, the true regret is what might have been: Flying saucers. Hover cars. A Lunar rover – and even the possibility of a Canadian using it.

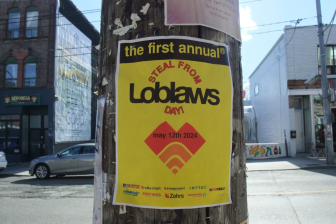

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- As Canada’s tax deadline nears, what happens if you don’t file your return?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Investing tax refunds is low priority for Canadians amid high cost of living: poll

“If the company had been left alone to continue the development process, Canada would have had a man on the moon,” Rob Cohen, CEO of the Canadian Air and Space Museum, told Global News. Pictured above: Avro’s concept for a lunar rover.

The fall of the Avro Arrow

So why was the Avro Arrow cancelled by the Canadian government in 1959?

“The government had an agenda to destroy it. They wanted the money for other things, so they came up with all kinds of reasons why they didn’t need it,” Squires said.

The reasons for the cancellation of the Arrow were a mix of politics, timing, and bad luck. The CF-105 (as the Arrow was officially known) was originally designed as a long-range interceptor, meant to meet and destroy Soviet bombers.

But on October 4, 1957 – the same day as the first Avro Arrow rolled off the production line – the Soviets launched the satellite Sputnik, becoming the first nation to put a man-made object into orbit.

And just like that, everything changed.

“It really was a case of the worst timing,” Squires said. “The same day as Avro rolls out their aircraft, you had millions of people around the world looking up at the stars, trying to look for Sputnik.”

That development changed the focus for militaries on both sides of the Cold War, away from conventional bombers and towards atmospheric weapons like intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Pictured above: One of Avro’s stranger projects, the “AvroCar” flying saucer (courtesy: wikicommons).

Then there was the often-contentious relationship between conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, and Avro Canada president Crawford Gordon, Jr.

“Diefenbaker didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, he was a complete teetotaler,” Squires said. “And in walks Crawford Gordon with his hip flask, a cigarette in his hand, pounding on Diefenbaker’s desk. They were complete polar opposites.”

There was also the changing politics surrounding the creation of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, or NORAD. One of the specifics of this deal was the purchase by the U.S. Air Force of the new Avro Arrow fighter.

“Diefenbaker just looked at it, said ‘looks good’ and signed it. Even Americans were shocked, because they expected some pushback.”

The cancellation of the CF-105 Arrow was a deathblow for Avro. It was also a serious setback for the Canadian aerospace industry as a whole.

What might have been

To many Canadian aerospace experts, the real loss in the cancellation of the Avro Arrow wasn’t just in the plane itself, but the possibilities for what Avro may have done in the future.

For instance, SPAR Aerospace, the company which designed the CanadaArm, was originally the Special Projects and Research branch (hence the acronym “SPAR”) of Avro Canada.

“Avro had a top secret design department with the brightest and most innovative thinkers. Total out-of-the-box thinking,” Cohen said.

Some of the special projects at Avro were right out of science fiction. Others were years ahead of their time. The company had plans for a lunar rover (pictured), a flying saucer (the “AvroCar”), and even a hovering truck.

Cohen notes other plans, such as a monorail system for Toronto from Union Station to what is now Lester B. Pearson airport, cameras that could capture and airplane travelling 1,300 mph and technology that could capture a rocket blast.

For Squires, the connection to Avro Canada is particularly personal – his father helped worked on the Avro jetliner, the C102.

“It broke four different records during first flight to New York,” Squires said. “If they had built the jetliner, they would have jumped 10 years ahead on commercial aircraft, and it would have given Avro another leg to stand on.”

Today, the legacy of the Avro Arrow is one of both pride and frustration for most Canadians.

This is especially true for Cohen. Two years ago, the Canadian Air and Space Museum was evicted from its home in the old de Havilland building in Toronto’s Downsview Park. The museum is currently trying to find a new home while most of its planes – including a full-size replica of an Avro Arrow – sit in storage at Pearson airport.

Cohen acknowledges that while funding was a problem, the main issue was a change in direction from above.

“Downsview Park has a whole host of new goals, and it’s obvious that the rich aviation history that once existed there is not part of their plans,” Cohen said. “A gun was to our head, and we had to do what we needed to do.”

All photos courtesy of the Canadian Air and Space Museum.

Comments