Scientists used beamlines at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) research facility to identify whether tungsten exposure raises health concerns.

A McGill University research group said it has identified the metal as problematic after determining high levels of it can accumulate and remain in bone.

“Our research provides further evidence against the long-standing perception that tungsten is inert and non-toxic,” PhD student Cassidy VanderSchee said in a press release.

The long-held belief was always that tungsten is safe. It has been tested for use in medical implants, such as hip replacements, and in some drugs. The metal also occurs naturally in groundwater where deposits of the mineral are present.

CLS officials said tungsten exposure via drinking water in Fallon, Nev., was investigated for a possible link with childhood leukemia in the 2000s. This investigation prompted toxicology and carcinogenesis studies in the U.S.

Get weekly health news

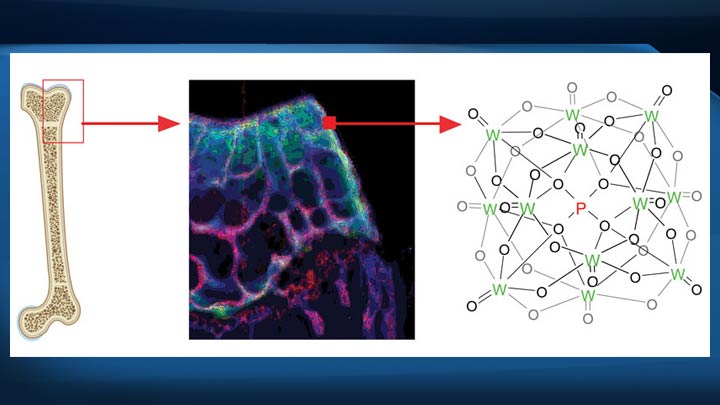

McGill scientists exposed laboratory mice to tungsten through drinking water and then examined their bones using CLS beamlines in Saskatoon.

Researchers found high concentrations of tungsten in bone marrow, and tissues responsible for immune cells and bone strength.

VanderSchee said she was surprised at research results that showed when tungsten accumulates in the bone, it persists even after exposure ceases.

“It is not washing out with time, which is concerning because if somebody is exposed to tungsten and you remove the source of exposure, that person may still have a chronic, low-dose exposure from tungsten remaining in their bone,” she said.

The researchers also believe tungsten changes forms as it interacts with the body’s chemistry. Animals were given simple tungstate, but when found later it resembled a more complicated, reactive form called phosphotungstate.

Now, the group wants to learn where and how the metal is chemically transformed with the goal of developing drugs that could remove it.

The McGill scientists conducted some of their research at the National Synchrotron Light Source II in Upton, N.Y.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.