Last fall, as Facebook faced criticism over political ads bought by Russian troll farms to influence the 2016 U.S. election, it opened the door just a crack to more transparency about political advertising on the platform.

Under new rules, political campaigns would have to display ads they are buying from Facebook on their pages.

The first country the rules would take effect in: Canada.

And, as chance would have it, the first major campaign where we can glimpse how it actually works is the Ontario Progressive Conservative leadership race. (On any candidate’s page, click on the three dots beside Share, and choose View Ads.)

We learn some basic facts from a look at the campaigns’ Facebook pages:

- Caroline Mulroney, Doug Ford and Christine Elliott are running extensive Facebook ad campaigns, with the content and approach changing frequently. On Tuesday, Mulroney was running three different (but very similar) negative ads targeting Kathleen Wynne, but by Wednesday, only positive ads were running. (Updated to change link to Ford’s Facebook page.)

- Tanya Granic Allen had no ads on Tuesday and a single video on Wednesday.

Ads vanish once they stop, so we can’t easily see how a campaign’s approach (for example, the shift of direction in Mulroney’s ads) has changed without regular checks.

WATCH: Facebook to roll out new standards in political advertising

An archive function will be revealed in the U.S. in time for midterm elections there in November, said a Facebook official speaking on background. The number of impressions an ad had, and basic demographic facts about who saw it, will also be public.

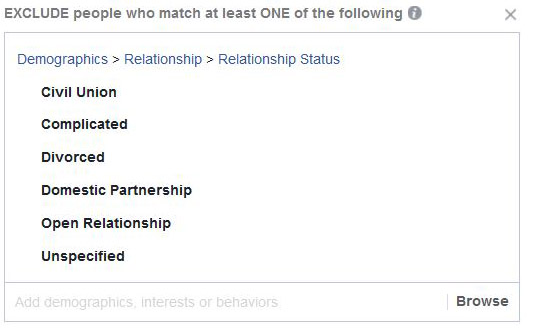

What will remain secret, however, is the demographic details of the ad buy. People buying ads on Facebook can create very detailed criteria about who they want them shown to (and equally detailed criteria of who they don’t want them shown to).

Facebook ad buyers can specify the location, sex, relationship status, education, age of children (for parents), and many, many more criteria — some proxies for ethnic affiliation. They can also use all the same criteria to exclude people.

Unlike in a general election, the PC campaigns are only interested in reaching a narrow group: party members who can participate in the leadership vote. Reaching those people accurately on Facebook might seem like a needle-in-a-haystack exercise.

But it’s easier than it sounds, a member of a campaign with knowledge of its social media strategy who spoke to Global News on background explained.

The campaigns all have access to the party’s membership list, which typically includes email addresses. In the case of about half the party’s membership — about 65,000 people — Facebook is able to connect those addresses to Facebook profiles.

Get breaking National news

Those profiles can then be broken down by all the demographic criteria and online behaviour (history of clicking on ads, or not) that Facebook keeps track of, and campaigns can target ads to them.

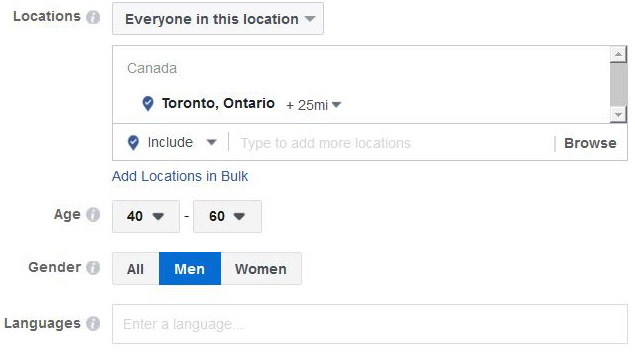

Because the campaign is very short, the campaigns aren’t targeting accounts with anything like the level of detail that Facebook allows, just basic criteria like sex, age and geography.

Some campaigns’ ads have been targeted at the Facebook accounts of university students who are party members, while other ads were shown specifically to women. An event can be advertised to party members’ Facebook accounts in the area.

WATCH: Trump social media strategist reveals Facebook worked directly for presidential campaign

The campaigns also concentrate advertising on Facebook accounts of members in low-population ridings where individual votes are worth more, the person said.

A longer campaign would offer the chance to reach people in a more granular way. Facebook breaks down parents’ accounts by the age ranges of their children, for example, and it’s not hard to imagine education-related ads that were tailored to different stages of the school system.

Another question is how the transparency rules can apply to third-party advertisers who don’t want to be identified. What if a Facebook page was registered as something other than a political cause — a business, say — and paid for negative political ads targeting a specific candidate?

The Facebook official spokesperson said that Facebook relied on automated systems screening for keywords and complaints, to look for stealth political ads.

The Mulroney and Elliott campaigns would not be interviewed for the record.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.