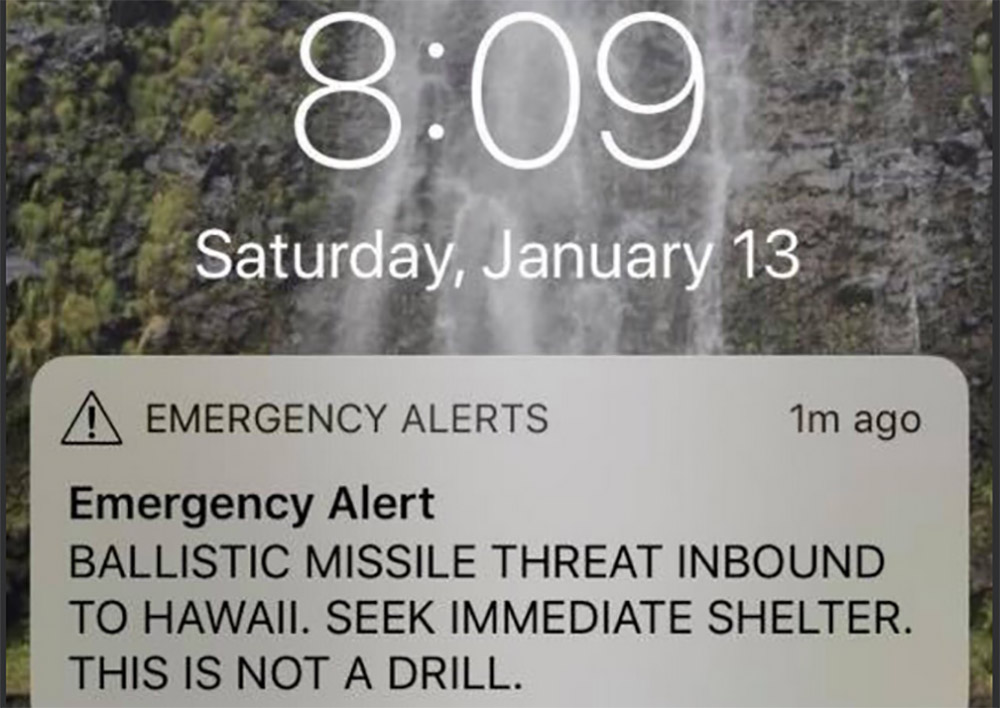

A mistaken emergency alert was sent to people in Hawaii on Saturday, warning them of an imminent missile attack. It wasn’t a real threat, but this didn’t stop people from panicking at the time.

Could the same kind of mistake happen here? Not yet anyway. Canada doesn’t yet have an alert system that sends messages to people’s phones – though we will soon.

Here’s how the current emergency alert system works:

1. A government agency decides to issue an alert.

Federal and provincial governments are hooked into the National Public Alerting System. If they see an impending disaster, they can decide to issue an alert. They decide what message to write and what geographical area to send it to, according to Martin Belanger, director of public alerting for Pelmorex, the company that operates the national alert system.

Alerts can be about a variety of issues, like fires, natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and civil emergencies. The government also decides the alert’s severity, including whether it should be broadcast immediately because it is about a threat to people’s lives.

2. The alert information gets sent to the distributor.

The government agency then sends the alert along to Pelmorex. The company aggregates all government alerts and pushes them out to broadcasters on television, radio, some internet and other news outlets, and beginning in April 2018, wireless service providers.

3. The alert is broadcast.

If it’s a “threat-to-life” alert, broadcasters must immediately send it out on their television channels and radio stations and interrupt regular programming to do so. These will usually start with a piercing, annoying tone to get people to listen.

“It’s meant that way. For good reason – you want to get the attention of the public in an emergency,” Belanger said.

Wireless alerts

Beginning on Apr. 6, 2018, a “threat-to-life” alert will also be sent by wireless providers to people’s cell phones, he said. They’re still working out what these alerts will look like, but they will likely incorporate the same annoying noise and have a common look and feel across all wireless providers and devices. So whether you have an Android phone on the Bell network or an iPhone on Rogers, the alert should look the same.

These alerts, sent in both official languages, will help Canadians “to take immediate action to protect themselves and their families,” according to a statement from Public Safety Canada.

“As the system expands to include the participation of cellphone companies, social media websites and other internet and multimedia distributors, even more Canadians will be alerted to emergencies that could affect their safety.”

There’s one caveat with the new wireless alert system though: the alerts will only be sent to devices on an LTE network, Belanger said.

Some smartphone apps — weather apps are an example — do currently exist through which warning messages can be sent. People in Ontario can also subscribe to a text-based “Red Alert” system.

Canadians can expect to start getting test messages on their phones in May as part of the overall testing of the entire emergency alert system – including the traditional broadcast alerts, Belanger said.

So, once Canada has a wireless alert system, could someone send a mistaken message?

- Alberta to overhaul municipal rules to include sweeping new powers, municipal political parties

- Grocery code: How Ottawa has tried to get Loblaw, Walmart on board

- Military judges don’t have divided loyalties, Canada’s top court rules

- Canada, U.S., U.K. lay additional sanctions on Iran over attack on Israel

Although Belanger didn’t want to comment on how Hawaii managed to send an alert message in error, he did note that there are a number of checks that have to be completed before an alert goes out.

“The alert issuers themselves, when they use the system to generate an alert, there’s some steps that they have to follow to make sure that the right alert is being created,” he said.

Not everyone has access to the alert creation system, and even those who do can’t necessarily create all kinds of alerts. If someone creates a “threat-to-life” alert, they have to confirm that they meant to send it. They also have to re-enter their credentials and password before hitting “send,” he said.

So, while in Hawaii someone “hit the wrong button,” in the words of Governor David Ige, in Canada, they’d at least have to enter their password first.

-With files from the Canadian Press

Comments