Daniel LeBlanc spends one night every week staring at the burned out shell of the home he lived in for more than 22 years.

“I’ll just drive my car over to 70 Niagara,” he said. “I’ll pull on to the street, so the car is facing the house, and I’ll play meaningful music that will make me emotional. That’s what I do Monday nights.”

It was just after 4 a.m. on Aug. 6, 2016 when LeBlanc, 26, awoke to the smell of fire and the sound of his brother screaming.

“Daniel, Daniel, Daniel!”

His brother was shouting from the floor below. A small kitchen fire, started by pot of unattended oil, had spread quickly and was now ravaging the family’s three-story home.

LeBlanc had no other warning that night – the home did not have working smoke alarms.

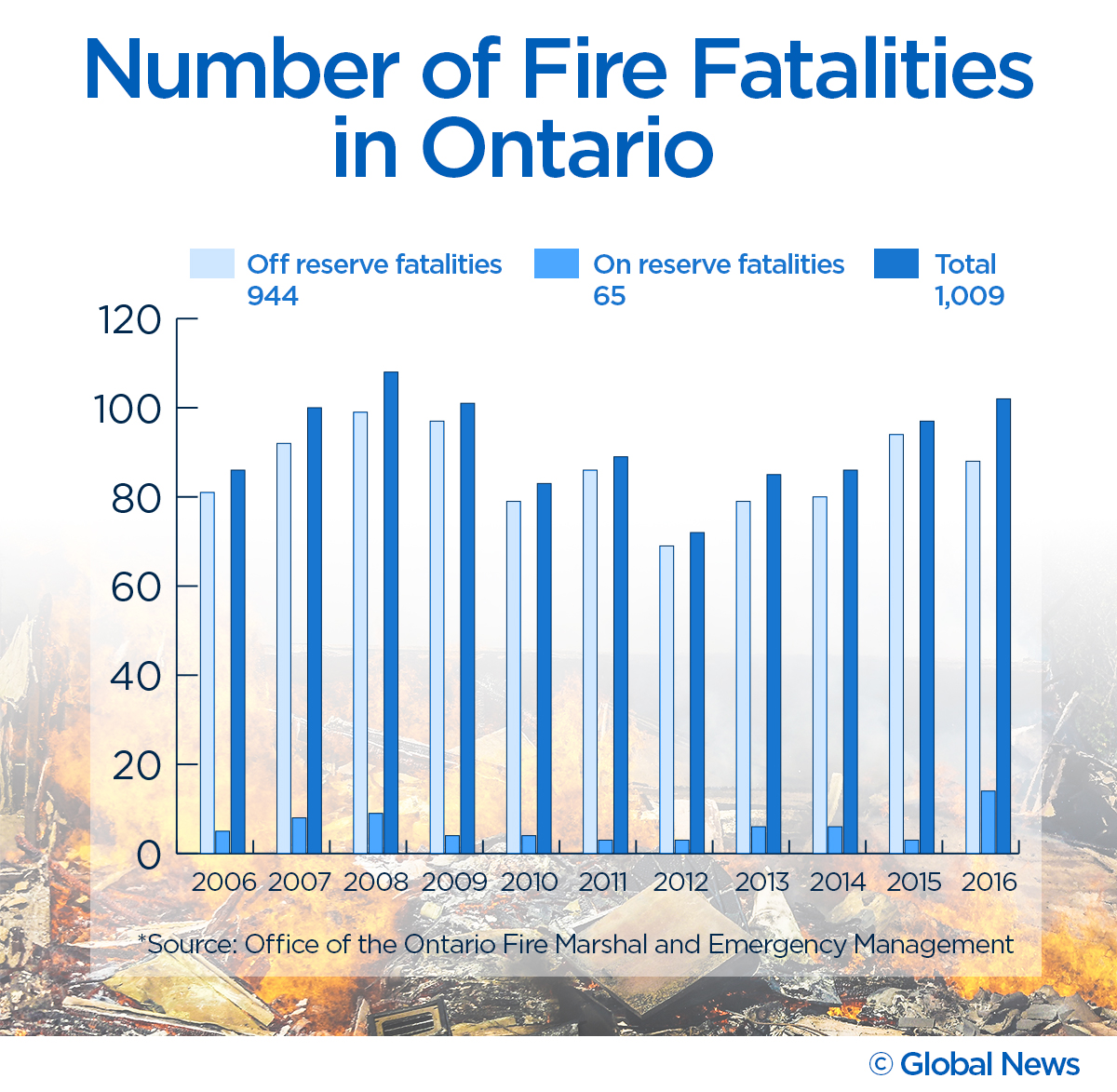

Last year in Ontario, 102 people died in 73 fatal house fires. It was the worst year for fire fatalities in the province since 2008.

READ MORE: Lack of working smoke alarms linked to 2 fatal fires in Hamilton: fire marshal

What makes these tragedies worse, say experts, is that many of fires – including that which killed LeBlanc’s family – could have been prevented. According to Ontario’s Office of the Fire Marshal (OFM) more than two-thirds of fatal house fires in the province happen in homes without functioning smoke alarms.

“2016 was a horrendous year for us,” said Dave Cunliffe, Hamilton’s fire chief. “We had 11 fatalities in residential structure fires. That’s probably the worst we’ve seen.”

LeBlanc survived the fire, but his girlfriend, Victoria Forrest, 26, her nine-year-old son, Robert, and their 18-month-old daughter, Abby, were killed.

“Sometimes, it’s even hard to close your eyes to go to sleep,” LeBlanc said. “Because you don’t want to dream about that night, or wake up to having that again.”

While the province-wide death rate from house fires has remained steady over the past decade – with roughly 90 people dying each year – Hamilton reported the highest number of fatalities last year since 1986, when 12 people died.

Cunliffe calls these fires “gut-wrenching.” House fires draw a crowd. Neighbours gather to watch as thick, black smoke fills the air. And when the worst happens – when a family member, friend or neighbour dies – the terror rips through communities like fire jumping from one window to the next.

“It’s built into every firefighter, you’ve got to make the rescue, you’ve got to save a life,” Cunliffe said. “That’s what you do.”

But by the time firefighters arrived at LeBlanc’s home that night there was nothing they could do. Witnesses to the fire described a scene of absolute chaos. LeBlanc’s mother, Yvonne, was on the lawn, screaming.

“My baby, my baby!”

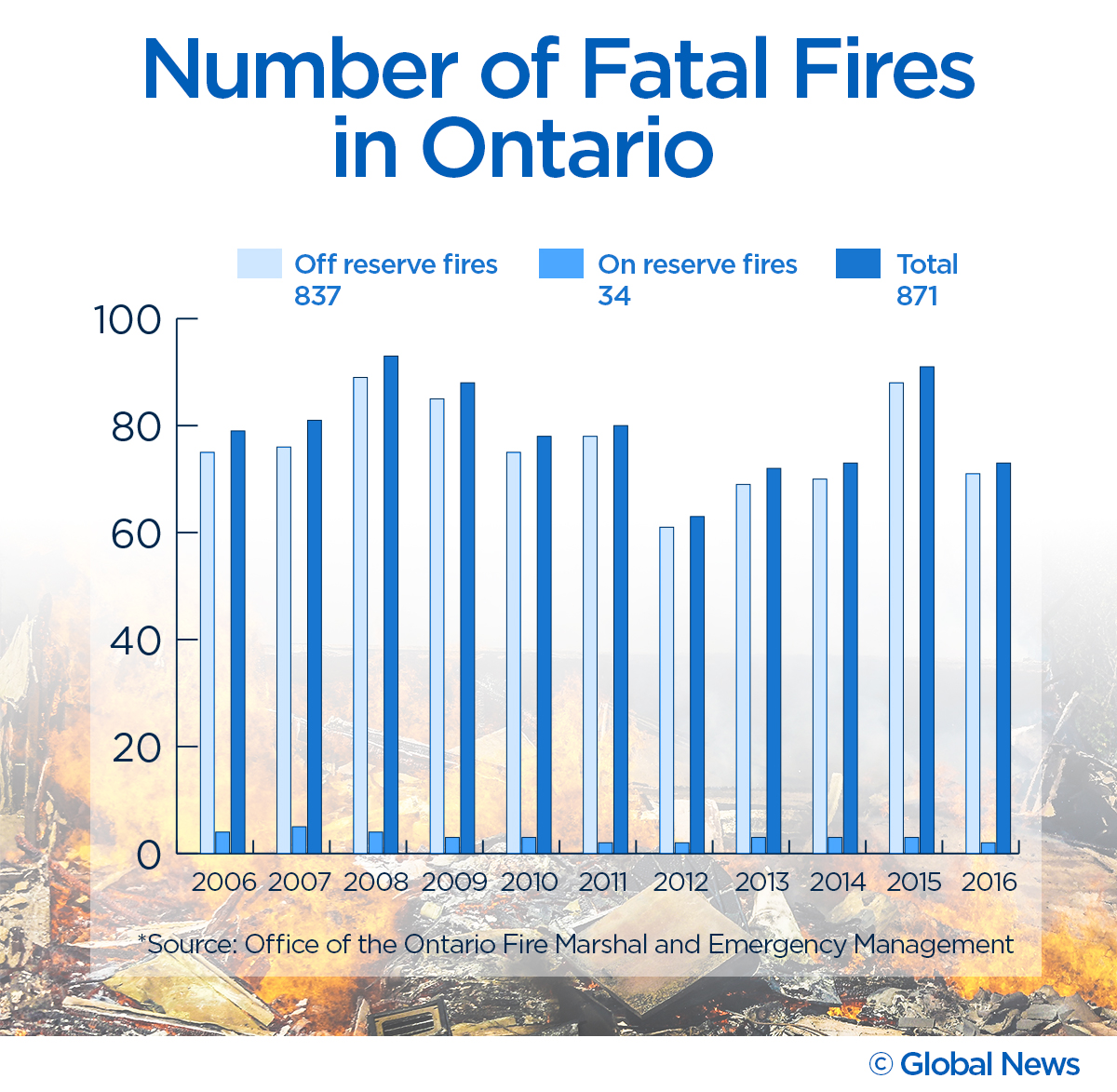

There were 871 fatal fires in Ontario between 2006 and 2016 – killing 1,009 people.

If fires involving arson are excluded – only about 30 per cent of these fires occurred in homes with functioning smoke alarms.

Around 35 per cent of fatal house fires in Ontario either do not have smoke alarms or the batteries did not work.

The remaining 35 per cent of fatal fires are either still under investigation or officials were unable to determine whether there was a smoke alarm.

Fires burn ‘faster’ and ‘hotter’ than ever before

Get breaking National news

For Leblanc – these statistics are a sobering reminder of where he and his family went wrong.

He says one of the worst memories from that night is knowing he didn’t kiss Victoria and Abby goodbye.

“Usually, I’d sing Abby to sleep, or pat her butt, she’d fall right to sleep.” he said. “I’d give her a kiss and Vic would sleep with me.”

But that didn’t happen that night. Instead, LeBlanc went to bed alone. He awoke to the sound of his screaming brother.

“I woke up, I was in a panic,” he said. “Victoria, she was actually trying to breathe out the back window.”

One of the last things he remembers from that night is Victoria saying she was coming, saying, “Let’s go.”

Everything is a blur after that, LeBlanc said. The smoke was so thick he couldn’t see as he descended the stairs. By the time he’d reached the ground floor, LeBlanc had to feel his way to the door.

He and his brother both tried to go back in but they couldn’t fight their way through the flames. All they could do was watch as Victoria, Robert and Abby died.

WATCH: Father who lost his girlfriend, baby in house fire struggles to move forward in new life

Ontario’s Fire Prevention and Protection Act requires all residential homes have working smoke alarms. Alarms must be placed on every level of a home and outside each sleeping area. The OFM recommends alarms be placed at the highest point on each level of the home and that residents check to make sure they’re working at least once a month.

Modern fires have far greater potential for destruction and devastation, Betts said. He cites recent studies that show typical house fires of today burn up to eight times faster than they did 50 years ago.

Having a prepared escape route and knowing what to do in the event of a fire is the best way to protect against injury and death, Betts says. But smoke alarms – much like seatbelts and airbags in a car – are a last line of defence against the unthinkable.

“In a fire you may have two minutes to escape, you may have 60 seconds,” Betts said, explaining how every fire burns differently. “You have precious few seconds to safely escape. That’s why it’s so important that you get that early warning that smoke alarms can provide.”

According to exclusive polling conducted by Ipsos on behalf of Global News – 99 per cent of Ontarians say they have functioning smoke alarms in their homes, while 95 per cent say they have smoke alarms on every level of their house.

Only 70 per cent of the 1,183 respondents said they have smoke alarms outside each sleeping area in their home.

People ‘don’t need to die,’ says fire chief

Following a fatal fire last December in which a mother, grandmother and two young children died, firefighters in Port Colborne, Ont. started going door-to-door to ensure residents were complying with the province’s fire code.

They knocked on nearly 1,600 doors in the town of less than 19,000 people – only 398 homes complied with provincial regulations.

Port Colborne’s fire chief, Tom Cartwright, thinks some people who responded to the Ipsos polling are “not being totally honest” with themselves.

“People should take more responsibility for their own lives,” Cartwright said. “People don’t ever think it’s going to happen to them. They don’t think they’re ever going to have a fire in their home. They just don’t.”

According to the OFM, nearly half of all fatal house fires in Ontario occur between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. when most people are sleeping.

READ MORE: Mother and two young children killed in Hamilton Ont. house fire

Cartwright – like many fire chiefs – is frustrated by the numbers. He’s frustrated when residents don’t do more to protect themselves, when landlords fail to maintain functioning smoke alarms – which is required under Ontario’s fire code – and when governments don’t do enough to promote fire safety.

“I think the role of the province should be as a leader,” he said.

Cartwright is grateful for the support his community receives through programs like the Ontario Fire College, which helps train and educate firefighters in the province, and from the Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs. But he says more can be done by the province to reduce deaths and encourage fire safety in Ontario.

Some of his ideas include more extensive advertising for fire safety – funded by the province – financially supporting smaller municipalities so they can ensure homes comply with provincial regulations, and innovations like mandating automatic sprinkler systems in all new residential constructions.

The province, meanwhile, says enforcement of the fire code is a municipal responsibility and that local fire departments – supported by the OFM – are in charge of education and fire safety within their communities.

“We must all do our part to protect and prepare ourselves,” said Marie-France Lalonde, Ontario’s Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services. “Home owners should remember to install working smoke alarms and carbon monoxide alarms. Everyone should have a fire safety plan and know the proper escape routes from their homes.”

Lalonde says Ontario’s fire code is among the most stringent in Canada and the only code with a “comprehensive retrofit component” that requires minimum standards for certain types of existing buildings – like those with basement suites and all multi-unit residential buildings.

Lalonde says she has not received any requests from local fire departments to fund awareness campaigns or enforcement efforts. However, she says anyone with ideas for improving public safety and compliance with fire regulations should contact the OFM.

Who’s responsible for smoke alarms?

In Ontario, landlords and homeowners are responsible for installing and maintain functioning smoke alarms – that includes replacing batteries and expired alarms. Recent changes to the fire act require tenants to check their alarms and notify landlords if there are any problems.

According to the Hamilton fire department, responsibility for maintaining smoke alarms in the LeBlanc family home rested with the landlord.

They say their investigation into the fire is now complete and multiple charges under the provincial fire act for failing to install and maintain functioning smoke alarms have been filed against the homeowner.

Hamilton Fire Chief says smoke alarms are vital because ‘seconds count’

Of the 11 fire fatalities in Hamilton last year, seven occurred in homes without functioning smoke alarms. Aside from the fire at 70 Niagara, only one other fatal fire resulted in charges.

On August 10, 2017, Charles Wristen – who was operating an unlicensed rooming house in the city’s north end – pled guilty to charges of failure to install smoke alarms and failure to maintain smoke alarms in working condition in connection to a fire that killed three people last October.

Wristen was fined $10,000 because of his guilty plea. Maximum penalties under the act are a $50,000 fine and one year in jail.

READ MORE: 3 dead, 2 in hospital after house fire in east-end Hamilton: police

LeBlanc, meanwhile, says anyone who hears his story should check their smoke alarms. If the alarms are not working – or if the batteries are dead – he says replace them.

Now LeBlanc does everything he can to move forward for their surviving son, six-year-old Dantay.

Asked why he chose to talk about his loss, LeBlanc said it’s important people understand that smoke alarms save live.

“On August 6, 2016, I lost three members of my family I’ll never get back,” he said. “Smoke alarms have saved lives before. If we had smoke alarms it probably would have made a huge difference that night.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.