The B.C. Court of Appeal’s stunning reversal of a lower court decision that found the Ministry of Children and Families (MCFD) allowed a Vancouver father to sexually abuse his kids is highlighting some major gaps in the justice system.

In part four of a CKNW special investigation, reporter Charmaine de Silva looks into the role that a lack of legal aid funding played in derailing justice for this B.C. family.

The B.C. Court of Appeal found that a Supreme Court judge’s decision was influenced by a fraudulent expert witness, despite the fact that she lacked credentials and never actually interviewed the father or the children.

The result? Kids who have been separated from their father for five years.

READ PART 1: How ‘flawed’ B.C. court rulings tore 4 kids away from their dad for 5 years and counting

READ PART 2: The B.C. judge who ‘ignored evidence,’ ‘erred in law’ and put a ministry under fire

READ PART 3: The family lawyer whose zealous advocacy missed ‘obvious red flags’ and helped an unfair trial proceed

It prompts the question: would this have happened if the father had a lawyer?

Would lawyers for the children, thrust into a legal battle between their parents, have made a difference?

TIMELINE: The longest child welfare, civil litigation in the history of Canada

A father’s legal options

B.G., the father, had a lawyer when the conflict with his ex-wife J.P. first entered the courts (whose names cannot be revealed because of a publication ban). But he didn’t have an advocate for long.

Paying for a lawyer is expensive, and if you can’t pay out of pocket, the options are limited: you access legal aid, or hope that someone will take on your case pro bono — and not be paid.

READ PART 2: the B.C. judge who ignored evidence

Neither of those was really an option for B.G. He didn’t qualify for legal aid, and no one wanted to take on this case pro bono.

“I was left with the decision, walk away because the allegations are meant to destroy you and if you can’t litigate, then walk away, give up, and you’ll never see your kids again, or fight and do whatever it takes, including showing up every single day in a suit pretending to be a lawyer,” B.G. told CKNW.

“So that’s what I did.”

B.G. showed up for every one of the 91 days of the family trial, and tried to be there for as much of the civil trial as he could. The latter trial lasted 146 days.

Get daily National news

The cases, which were both heard by B.C. Supreme Court Justice Paul Walker, resulted in devastating judgments.

But it wasn’t until the judgment in the civil trial that B.G. managed to secure counsel, pro bono.

By then, concerns raised by Walker’s decisions were seen as a matter worth addressing in the appellate court.

With lawyer Morgan Camley on the case, B.G. could now have his appeal heard — despite being long past the time limit for filing.

In the end, he won his case: B.C.’s top court ordered a new family trial and the findings against him have been set aside.

Things could have ended differently

But before that happened, the first two trials ruined reputations, destroyed lives and saw the children separated from one parent for five years.

Experts said the case could have ended differently if the father had his own counsel.

“There is a real issue here of justice,” said Erez Aloni, an assistant professor at UBC’s Allard School of Law, who specializes in complex family relationships.

“You ask yourself if he were represented properly if these kinds of admissions of evidence would have been accepted. And my answer is, ‘Likely not,'” he said.

The Court of Appeal ordered a new family trial, mainly because the judge accepted and relied on evidence from a problematic expert that J.P., the mother, had submitted.

The higher court found that expert – Dr. Claire Reeves – didn’t have proper credentials and that she never interviewed either B.G. or the children.

“Because there was no lawyer on the other side, there was probably no rebuttal or no insight into whether these credentials were legitimate,” said Georgialee Lang, a family lawyer with 25 years of experience in trial and appellate courts.

She said numerous experts testify frequently in B.C. They’re known to people who work in family court, she added.

“The judge, when a lawyer presents an expert, accepts the submissions that this is an expert and the credentials are legitimate, but in this case, that was not true,” Lang said.

If B.G. had a lawyer, they likely would have had problems with Reeves, she added.

Most family law matters involved self-represented litigants in 2015

The court also saves time and the justice system saves money when all parties have legal representation in a complex family dispute, Lang said.

“It’s very difficult, and the judges are decrying it right from coast to coast because it’s happening right across Canada, and I imagine, in the United States too.”

Self-represented parties were involved in 57 per cent of family law matters that made it to the B.C. Court of Appeal in 2015. Trials can last longer when a party lacks representation, Aloni said.

The far-reaching impacts of a case like B.G. and J.P.’s speak to the court system’s ability to provide real justice, he added.

“When we have people fighting over essentially something that is the best interest of the child, letting them litigate, that alone creates — beyond the lack of efficiency — a serious unfairness, especially if there is asymmetry,” Aloni said.

“This case is, again, the best example for that.”

Who represents the children?

It wasn’t just the father who went without representation in this case; the children didn’t have their own lawyers, either.

It’s a problem that’s been highlighted by Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, B.C.’s former Representative for Children and Youth (RCY).

Kids should have access to legal counsel who are trained to work with children, and who can stay “steadfastly focused” in cases where the system needs to resolve matters more quickly, Turpel-Lafond argued.

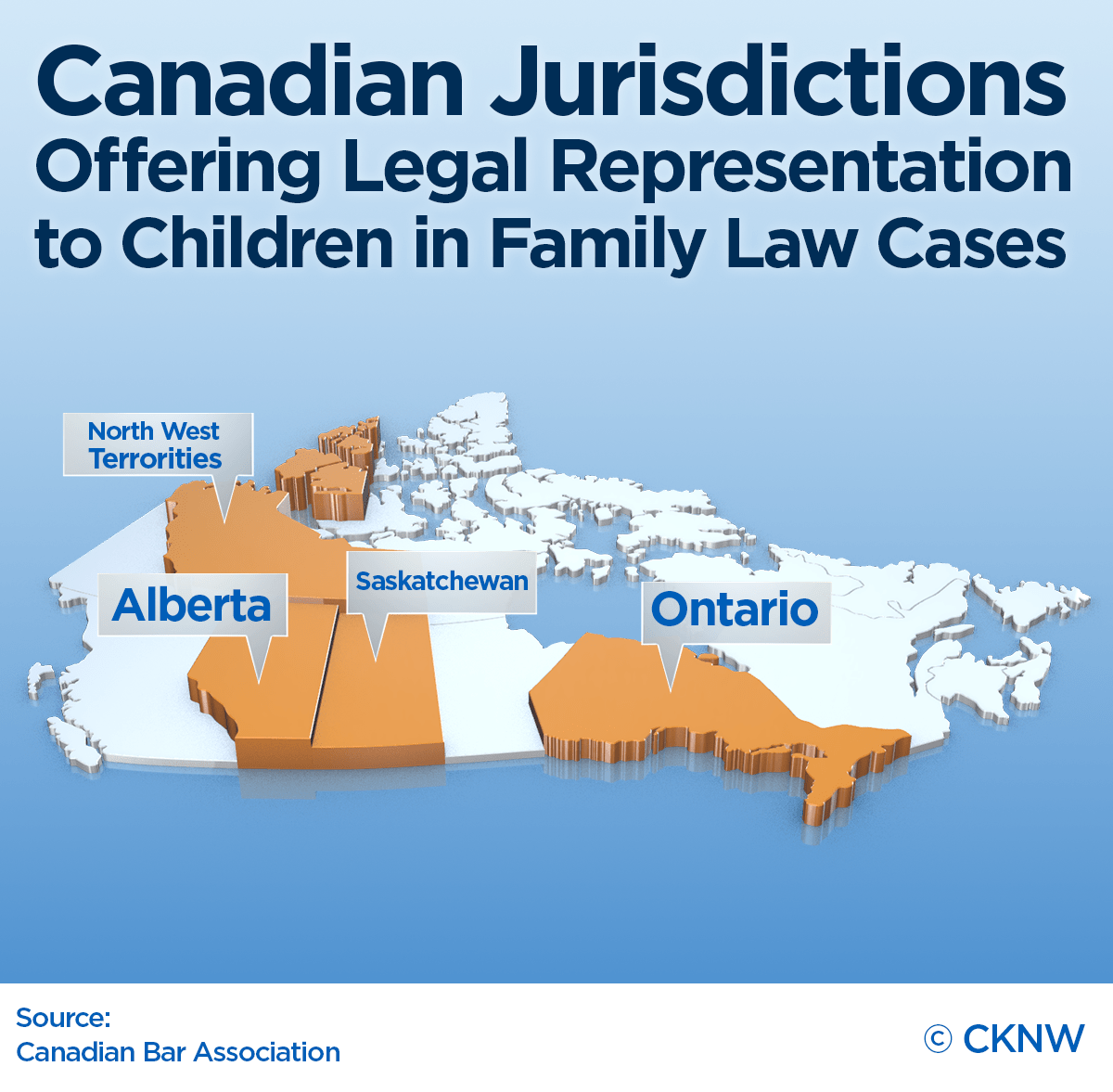

Some provinces — Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan — offer legal support for children in complex family cases. B.C. doesn’t.

Those lawyers can ensure that children’s rights are always taken into account, she said.

B.C. had a children’s lawyer program two decades ago, but it was dismantled. Turpel-Lafond said she pushed the province, the law society and legal aid to revive it during her decade as the children’s and youth rep.

The province didn’t bring it back. But Turpel-Lafond wasn’t surprised.

“I think in British Columbia, it hasn’t been established because they refuse to spend the money, they refuse to see the value,” she said.

Costs

At the heart of the issues surrounding the lack of legal representation is the question of the extent to which legal aid should be funded.

As it stands, the system is hanging by a thread.

Funding to legal aid was cut by 40 per cent when the BC Liberals came into power in 2001.

The lion’s share of legal aid is directed to serious criminal cases, with family law cases — even complex ones — often being left out.

And the government knows there’s problem — the BC NDP pledged to increase funding for legal aid during the most recent election campaign.

That promise has been praised by both the Law Society of B.C. and the B.C. branch of the Canadian Bar Association.

Nancy Merrill, the law society’s second vice-president, said that with a new government, there’s lots of hope that the promise will be acted upon. But so far, it hasn’t been fulfilled.

WATCH: B.C. legal aid cuts hurt women leaving abusive relationships

There was no boost to legal aid funding in the NDP’s September mini-budget.

However, in a statement, Attorney General David Eby said his government is committed to taking action by improving legal aid and dispute resolution services for families.

He said the province has “started the work required to get access to justice for British Columbians, and our courts back on track.”

READ PART 5: How B.C.’s ill-equipped system spawned the longest child welfare fight in Canada’s history

Comments