At the risk of coming across as a cruel and heartless monster, it would appear as though a case needs to be made against laws banning so-called “price gouging.”

Most people, I suspect, have a rather low opinion of those who would seek to profit on the backs of those adversely affected by a natural disaster. While such moralistic impulses are understandable, not all well-intentioned policies have desirable outcomes.

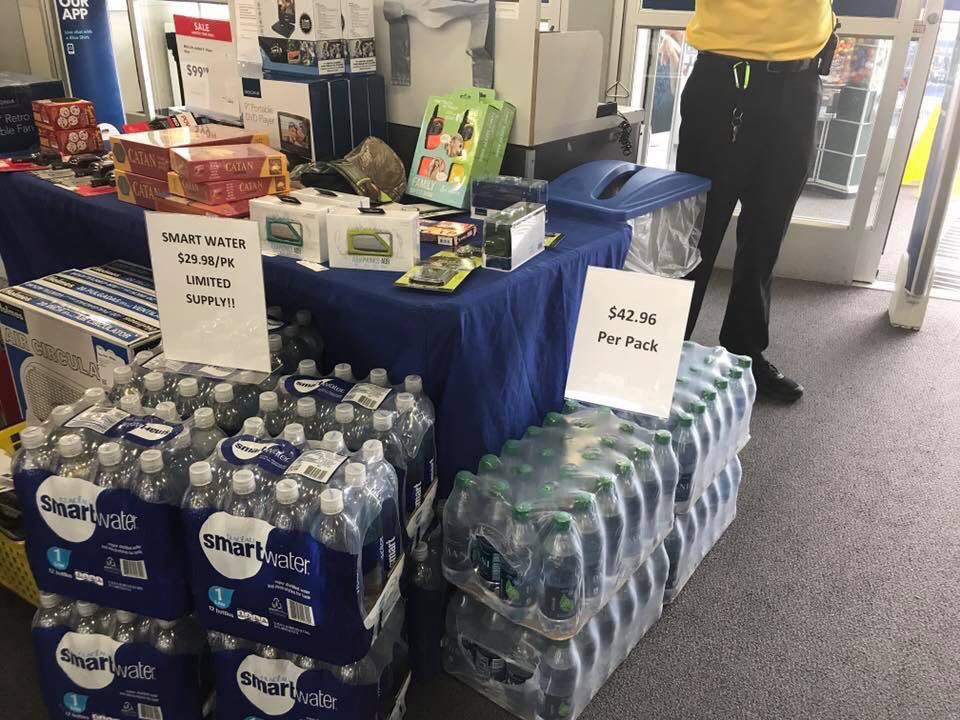

In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, the office of the Texas attorney general is investigating upwards of 600 complaints of price gouging in the Houston area, most involving bottled water and gasoline. In one high-profile instance, Best Buy was forced to issue an apology after a photo taken at one of its stores showed a 24-pack of bottled water selling for $42.96.

READ MORE: Major southern gasoline pipeline shuts down in wake of Harvey

The exact same thing happened in Calgary in the aftermath of the devastating 2013 floods. Home Depot was forced to apologize after photos emerged on social media of 24-packs of bottled water selling for $42.

Bottled water is an interesting example. In bulk, bottled water can be purchased for what works out to less than a dollar a bottle, often even less than 50 cents a bottle. Yet, when sold individually, it’s quite common at movie theatres, concerts, sporting events, amusement parks, hotel mini bars, and elsewhere to pay four or five dollars a bottle – or even more.

Given that, the outrage over the Best Buy price seems a little misplaced. Perhaps they should have just opened up the pack and sold the bottles separately.

Get breaking National news

READ MORE: Houston morgue pushed to near-capacity by Hurricane Harvey flooding

- Danielle Smith promises Alberta referendum over immigration, Constitution changes

- ‘No reason to continue discussing’: Ontario mayor wants Andrew’s name dropped

- Canadian Tire says Triangle Rewards are its ‘linchpin’ for growth

- Porter flight from Edmonton loses traction, slides off taxiway at Hamilton airport

But what is the value of a bottle of water in the first place? Or, more to the point, what was the value of those particular bottles of water? We, of course, rely on market forces to determine what we consider to be the “normal” value of such commodities, but these extreme situations don’t necessarily represent a failure of those market forces.

Excessive demand coupled with scarce supply has inflated the value of the product. We could, as price gouging laws do, simply demand that the retailer leave the price unchanged from where it was previously. Unfortunately, that may prove to be counterproductive.

READ MORE: Hurricane Harvey: Authorities warn of fraud, storm-related scams in wake of flooding

This is something that many economists have studied quite extensively. And not just conservative or libertarian economists, either. In 2012, for example, in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, prominent progressive economist Matthew Yglesias wrote a piece arguing that anti-price gouging laws were “hideously misguided.”

He noted that such laws merely “exacerbate shortages and complicate preparedness. Letting merchants raise prices … creates much-needed incentives for people to think harder about what they really need and appropriately rewards vendors who manage their inventories well.”

In other words, the higher prices help ensure that such resources are allocated based on need, rather than first come, first serve. It also helps ensure that people are not hoarding or buying more than they need. By tempering demand, supplies won’t be depleted as fast. Is it not better to have paid a slightly inflated price for bottled water than to encounter empty shelves?

Moreover, it sends an important signal to the market that the shortage exists. As economist Don Boudreaux has observed, “higher prices are … not the problem; they reflect the problem.”

The solution, therefore, is to increase the amount of available supply — and higher prices provide a necessary incentive. In a 2015 study, economist Steven Suranovic points out that “the market does a remarkably effective job of allocating the scarce goods fairly and helping to eliminate the shortage more quickly.”

Emotion, though, is a powerful force, and I doubt the public revulsion around “price gouging” is going to disappear anytime soon. In fact, it’s likely that a fear of public shaming and negative media coverage keeps this phenomenon relatively limited.

However, it seems clear that circumventing market forces in pursuit of some vague goal of perceived fairness actually leads to worse outcomes for those we’re purporting to help. That should count for something.

Rob Breakenridge is host of “Afternoons with Rob Breakenridge” on Calgary’s NewsTalk 770 and a commentator for Global News.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.