OTTAWA – The federal government secretly gave RCMP security officials the authority to tap telephone calls without court oversight during the Cold War, newly unearthed archival documents show.

The surveillance program, codenamed “Picnic,” began as an emergency effort during the Korean War, but federal agencies collaborated with telephone companies in 1954 to continue the wiretaps, says Dennis Molinaro, who teaches history at Ontario’s Trent University.

Molinaro’s research indicates the RCMP security branch was listening in on the embassies of East Bloc countries, “certain unfriendly organizations” and individuals suspected of disloyalty.

It has long been known the Mounties kept an eye on a wide array of people and organizations – from church and gay rights groups to Quebec separatists and Communists – in the name of national security, amassing hundreds of thousands of dossiers.

Mountie scandals in the 1970s led to a royal commission, the demise of the RCMP security service and creation in 1984 of the civilian Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

READ MORE: Canada shelled out $6M to clean up Cold War bases in Germany: documents

Molinaro believes the documentation he has uncovered with the help of tenacious staff at Library and Archives Canada helps flesh out how the RCMP surveillance of Canadians took place and implicates federal politicians and bureaucrats in making it happen.

The issue of when – and how easily – police and intelligence services should be allowed to intercept personal communications continues to play out today, fuelled by former U.S. spy contractor Edward Snowden’s revelations of widespread surveillance.

“We can’t evaluate where we’re going next – or even where we are in the present, accurately or effectively – if we don’t know where we’ve been,” Molinaro said in an interview.

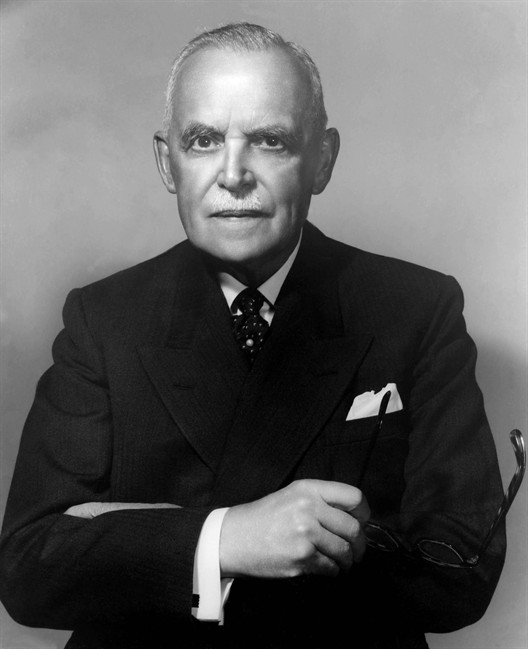

As hostilities in Korea unfolded, the Liberal government of Louis St-Laurent issued two dozen orders-in-council in the early 1950s under the Emergency Powers Act, Molinaro notes in a draft chapter on the episode from a forthcoming book.

READ MORE: Mountie spies grilled Herbert Norman’s widow years after diplomat killed himself

Many of the measures were mundane, but order-in-council 3486, passed on July 4, 1951, was withheld from publication. St-Laurent would later describe it to the House of Commons simply as a measure that concerned the combined security of Canada and its NATO partners.

The secret order-in-council authorized the RCMP’s Special Branch to tap telephones – a power the government wished to preserve even after the truce in Korea, Molinaro says.

Senior Privy Council Office adviser Peter Dwyer suggested entrenching and broadening the authority through an amendment to the Official Secrets Act.

This posed a problem in the mind of Paul Pelletier, assistant secretary to the cabinet. In a November 1953 letter to Stuart Garson, justice minister at the time, he said such an amendment would attract unwanted attention. He felt the most “effective smokescreen” would be a series of amendments to ensure the real goal – wiretapping phones – would be “more or less successfully beclouded.”

READ MORE: New Diefenbunker owner looking to preserve its future

The government eventually settled on amending section 11 of the Official Secrets Act as the statutory basis for wiretap warrants presented to telephone companies by the RCMP commissioner or his deputy, without judicial scrutiny.

“How long the program continued and how large it grew is not known,” Molinaro writes.

Though Library and Archives staff helped him piece together elements of the story, Molinaro’s attempts to locate order-in-council 3486 have proven futile. Archivists found evidence that Norman Robertson, the Privy Council chief of the day, was told to “retain” the order and keep it in a security “vault” somewhere in the halls of government, he writes.

Molinaro has filed a complaint with the federal information commissioner in a bid to dislodge the text.

“We have a long way to go in terms of accessibility to information for researchers,” he said. “This is a problem when you’re trying to write history.”

- Canadian man dies during Texas Ironman event. His widow wants answers as to why

- On the ‘frontline’: Toronto-area residents hiring security firms to fight auto theft

- Honda’s $15B Ontario EV plant marks ‘historic day,’ Trudeau says

- Canadians more likely to eat food past best-before date. What are the risks?

Comments