HALIFAX – Looks can be deceiving. Such is the case when the untrained eye looks at a weather map.

Hurricane Leslie could churn toward Canada’s east coast in the next week, while Hurricane Michael continues to intensify in the eastern Atlantic Ocean.

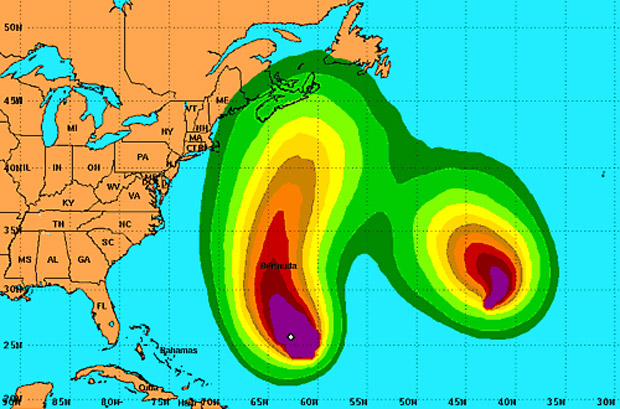

The projected paths of the two storms remains uncertain, but images of the systems look as though the two might be on a collision course.

A graphic depicting wind speed probabilities for Leslie and Michael over the next five days looks as though the storms could merge.

That prompted followers of the Atlantic Hurricane Centre Facebook page (not an official meteorological agency) to speculate about the formation of “the Perfect Storm.”

The Perfect Storm

Between Oct. 28 and Nov. 4 1991, a deadly weather event formed off the northeastern United States, after Hurricane Grace turned east from the Western Atlantic and merged with a non-tropical low pressure system that formed along a cold front moving off the coast.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said “the vigorous cold front from the extratropical low undercut and quickly destroyed Grace’s low level circulation east of Bermuda,” drawing the remnants of the hurricane into the centre of the storm as it continued to grow.

The system became known as the Perfect Storm, in part, because of a book by journalist Sebastian Junger and a Hollywood movie by the same name, which chronicled the deaths of six fishermen aboard the Andrea Gail.

Get daily National news

The Andrea Gail – a Gloucester, Mass. based fishing boat – sank northeast of Sable Island, N.S. during the storm, in waves that were believed to have reached 30 metres or higher.

According to Canadian officials, the potential for that to happen with Hurricanes Leslie and Michael doesn’t really exist.

The Canadian Hurricane Centre points out the two storms are actually quite far apart and have a large area of high pressure around them.

The Hurricane Centre’s Dr. Chris Fogarty says the likelihood of Leslie and Michael influencing one another is very low.

“I’d say like five per cent or less,” he says.

“These storms are deeper down in the tropics,” Fogarty explains, adding “it’s pretty rare to get hurricanes merging in the Atlantic Ocean.”

He says when two hurricanes get closer to one anther the larger of the storms will draw in some of the moisture, making for a “rainier, wetter hurricane.”

But you won’t get some sort of super hurricane, because the larger storm will basically break the smaller one apart.

The Fujiwara Effect

While it’s rare for two hurricanes to merge in the Atlantic, it does happens more frequently with typhoons in the Pacific ocean.

“Every two or three years there will be two (Pacific) storms that interact with each other,” Fogarty says.

When this happens, an interesting phenomenon known as the Fujiwara Effect can occur.

As one cyclone advances toward another — getting within about 1,450 kilometres — and the storms begin to interact, the weaker of the two may begin to orbit around the outer edge of the more dominant system.

After one or two rotations, the stronger storm will either begin to absorb the other or send it spiraling in another direction.

In the Atlantic Ocean, this happened in a particularly active period of the 1995 hurricane season when four named storms were swirling in the open Atlantic: Humberto, Iris, Karen and Luis.

In fact, the effect happened twice with one very persistent and erratic storm – hurricane Iris.

The U.S. National Hurricane Center explains on its website that Hurricane Iris had its first Fujiwara interaction with Hurricane Humberto near the near the Lesser Antilles, causing it to weaken to a tropical storm.

The two storms didn’t merge and Iris began moving along a different path and encountering Tropical Storm Karen.

On August 30 of that year, Hurricane Iris began to interact with Karen, which was developing to the southeast.

This time, Karen got caught up and began to circulate around Iris before dissipating and becoming a part of the hurricane.

Iris eventually became a Category 2 hurricane, with maximum winds of 175 km/h, before moving into the northeast Atlantic and dissipating

A Fujiwara Effect also occurred in 2005 – the busiest hurricane season on record – when Hurricane Wilma absorbed the remnants of Tropical Storm Alpha off the north of Hispanola on Oct. 24.

The Fujiwara Effect is named after the Japanese meteorologist who first explained the occurrence, Sakuhei Fujiwara.

*With files from the U.S. National Hurricane Centre, the Canadian Hurricane Centre and Global’s Mayya Assouad

Comments