There’s a revolution in cancer treatment.

“It’s been a roller coaster ride,” said Dr. Howard Kaufman. “We’ve attempted to say we’ve cured cancer many times, there’s a lot of Time magazine covers and Newsweek covers that say ‘Is this the cure?’ that go back 20 years and never has been,” Kaufman told Global News’ 16×9. “But this is different.”

“This is it.”

The new hope and optimism is immunotherapy. A cancer treatment designed to boost the body’s natural defences to fight cancer. The disease kills one in four Canadians.

“Given what we’re seeing, we really think that this is a possibility at least for some patients,” said Kaufman, a surgical and medical oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

WATCH ABOVE: Dr. Howard Kaufman is a surgical and medical oncologist at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. As a leader in the field of immunotherapy, he feels a cancer cure for some patients could be a reality.

READ MORE: Behind the science of cancer-fighting immunotherapy

The three main ways to treat cancer patients are by using surgery, radiation or chemotherapy – these are referred to as the three pillars of cancer treatment. Now immunotherapy is considered to be emerging as the fourth pillar.

The hope is one day immunotherapy can help treat all cancers.

“I would say that probably all types of cancers eventually will be able to be targeted by immune therapy,” Marcus Butler, a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, told Global News’ 16×9.

WATCH ABOVE: Dr. Pamela Ohashi is the Director of the Tumour Immunotherapy Program at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. She outlines some of the successes of immunotherapy.

In basic terms, immunotherapy harnesses the body’s immune system’s ability to fight and kill cancer cells.

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) February 2016 report, two main strategies of immunotherapy are now being explored, “the first involves unleashing the body’s natural immune response to cancer, and the second helps the immune system find and destroy cancer cells.”

Not all immunotherapies work the same way. According to the U.S. National Cancer Institute, “immunotherapies either stimulate the activities of specific components of the immune system or counteract signals produced by cancer cells that suppress immune responses.”

“When we talk about immune therapy, we’re using agents that target the immune system instead of targeting the tumour directly. In other words, we try to induce a T-cell or some other type of immune cell to be able to target and kill the cancer cells,” Butler said.

The concept of using immune therapy has been around since the late 1800s, but in the last 15 to 20 years, researchers have gained better understanding of how the immune system works, and those discoveries have led to new therapies and treatments.

For now, there are only a handful of immunotherapy drugs available in Canada. Researchers and physicians are developing new treatments, which some Canadians are getting access to through clinical trials.

The patient experience

WATCH ABOVE: Jeanette Edl tried surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but her cancer kept spreading, then she enrolled in an immunotherapy clinical trial.

She’s just finished treatment and Jeanette Edl is sitting on a bed at Princess Margaret smiling and laughing – she knows the fact that she is here at all is “a miracle.”

Edl has been battling cancer for almost six years. She tried surgery, radiation and chemotherapy – she had small victories only to be faced with a return of the cancer and it kept spreading.

Get weekly health news

Then she was told it was stage four. There is no stage five.

“Things were not heading in the right direction,” Edl said. “I had several tumours in my lungs that were growing pretty rapidly…things were really in a very bad stage.”

When she arrived at Princess Margaret her physician knew Edl was running out of options.

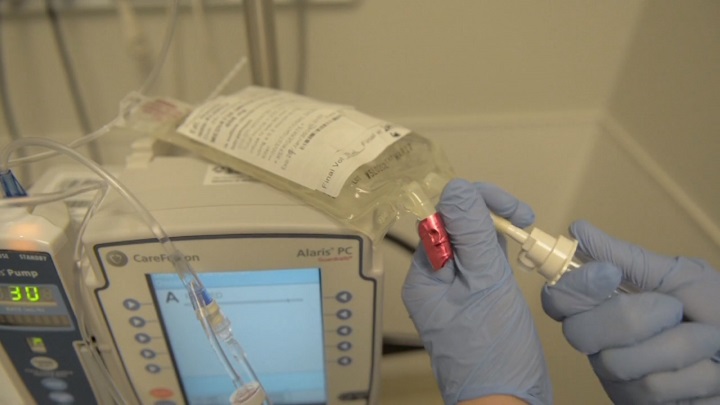

Butler is her oncologist. He’s also the director of the immune monitoring laboratory at the cancer centre. He thought immunotherapy might be able to help Edl. So she enrolled in an immunotherapy clinical trial of a drug she takes intravenously.

Within a few months, her cancer started disappearing.

“So with the great turnaround of immunotherapy, it’s like a miracle to me,” said Edl.

Edl says her cancer has shrunk by at least 70 per cent.

“So she’s had a really impressive clinical response with the tumours that were seen on scans,” Butler said. “When we look at the scans, there’s a possibility that that 30 per cent residual is actually just scar tissue.”

Edl also likes to talk about one of the other remarkable patient experiences with immunotherapy – the lack of or minor side effects. Patients report flu-like symptoms: fever, nausea and headaches.

Edl has joined a growing group of patients who have had success on immunotherapy.

READ MORE: Former US president Jimmy Carter no longer needs cancer treatment

One of the most well-known is former U.S. president Jimmy Carter. In 2015, Carter, 91, announced he had stage four melanoma in his liver and brain. He was treated with radiation and the immunotherapy drug Keytruda. He says he’s cancer-free and no longer needs treatment. He will continue to be monitored.

Although the success rate of immunotherapy treatment varies, doctors are encouraged by the results they are seeing in different cancers, including kidney, lung and melanoma.

Before immunotherapy there were limited options for patients with advanced melanoma – the deadliest form of skin cancer.

“If you talk to the clinicians in the melanoma clinics, their clinics are now just overrun with patients who are surviving longer,” said Pamela Ohashi, director of the tumour immunotherapy program at Princess Margaret. “So this whole therapy has really been a game changer.”

“Approximately 30 per cent of the patients will respond. And that means their tumours shrink to some degree, if not completely shrink and disappear altogether.”

But like all cancer treatments it isn’t effective for everyone.

Pamela Brush has been battling alveolar soft part sarcoma for nearly 20 years. She’s tried surgery and radiation – but the cancer kept spreading. So her doctor recommended an immunotherapy trial. She says the treatment worked for awhile and then it stopped.

“I was devastated,” Brush said. “This whole year everything was fine, no side effects, no bumps, nothing. And then right at the very end … there was another tumour that popped up.”

She recently finished a round of radiation, and says she just started on a new immunotherapy trial hoping it will be her answer. With such a rare cancer, it’s her best hope.

“Yes. It is my only option.”

As promising as immunotherapy is, researchers are still trying to determine why some patients respond and others do not, and if there is a way to combine or tailor the therapies for each patient and cancer.

“The biggest challenge we have right now is that not every single patient benefits. And, in fact, in many cases, the majority of patients don’t have these long-term benefits from treatment, so we need to figure out how to make it so that everyone benefits from treatment,” Butler said.

Natural killers – using viruses to kill cancer

We often think of viruses as enemies. Now they are a promising cancer-fighting tool.

It’s a form of immunotherapy called oncolytic virus therapy – using live viruses to kill cancer.

“Viruses are really nature’s way of stimulating an immune response,” Kaufman told Global News. “So if you ask, ‘What is the most powerful way to get an immune response in any host?’ it’s really using a virus.”

Herpes virus

Kaufman is an international leader in the field. In clinical trials he and his team tested a modified herpes virus in patients with melanoma.

It too activates the immune system, but there’s more. The drug in this case, T-VEC, is injected directly into the tumour, the cancer cells are destroyed and then release more of the virus into the body, and at the same time the immune system is called into action to fight.

In October 2015, it became the first virus cancer treatment to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

According to Kaufman, close to 26 per cent of study patients with melanoma had some sort of tumour shrinkage, and close to 11 per cent saw their tumours disappear entirely.

At Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, patient John O’Donnell had stage four melanoma that had spread to his lungs. All other treatments had failed. The survival rates for late stage melanoma are “dismal.”

So he enrolled in the modified herpes virus trial.

WATCH ABOVE: John O’Donnell was diagnosed with melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. He believes he is alive today because of immunotherapy.

“Dr. Kaufman had noticed that after the first treatment, already he felt a difference in the hardness of the lump that was under my arm,” O’Donnell said. “As my treatments continued, it got smaller, smaller, smaller … to the point where they were able to just remove it.”

He says it also cleared up the cancer that had spread to other parts of his body. Right now he is cancer-free. He will continue with check-ups to make sure. He believes the modified herpes virus saved his life.

“I’m sure that’s what did it for me. You know, as far as I’m concerned – it’s a near miracle. And I’m more than happy with the results,” said O’Donnell. “Unbelievable. It was just unbelievable.”

Currently researchers around the world are trying to develop the next virus to be approved for use in patients.

The Canadian virus fighting duo

At the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, senior scientist Dr. John Bell and his team across the country have developed a combination strategy.

The first in the world to do so, they are testing the Miraba virus, found in the Brazilian sand fly and a common cold virus, Adenovirus. Both viruses have been modified.

“We’re pretty excited about this approach. I think this combination strategy is really going to be a game changer we think,” Bell told Global News’ 16×9.

Bell’s team is at the clinical trial phase.

READ MORE: Viruses that can destroy cancer? Canadians leading the way in new research

Bell’s next line of attack is to combine oncolytic viruses with other immunotherapy drugs to eradicate cancer.

“At trial we combine immune cell therapy with the virus therapy,” Bell said. “It makes a lot of sense to us. It’s sort of like bringing in the army, the navy, and the air force as opposed to just bringing in one approach to kill the cancer.”

He also believes one virus treatment will not work for all patients.

“Everybody’s tumour is unique to their body and their genetic makeup,” said Bell. “So the same way some people get a bad flu and others don’t, some viruses will actually work on some tumours but not others.”

READ MORE: Oncolytic viruses: North American scientists test new therapy to fight cancer

“So we’re going to need a spectrum of virus products to be able to attack all the different kinds of tumours that happen within people based upon a genetic makeup,” said Bell. “I think it’s likely you’re going to see a half dozen viruses as proof products in the future.”

Immunotherapy’s future

Developments in immunotherapy are happening quickly. The American Society of Clinical Oncology named it the “advance of the year.”

In addition to the developments in the area of oncolytic viruses, researchers are also attempting to create new treatments that are individually tailored to individuals; personalized cancer care.

That is still years away. But immunotherapy is taking its place in the cancer treatment field, as it continues to revolutionize cancer care.

“It’s fantastic, and that’s really changed the thinking in the field. I would say five years ago, 99 per cent of the clinicians wouldn’t – they didn’t believe in immune therapy,” said Ohashi. “And now it’s completely the other way around. That’s all they talk about. That’s where the successes are. That’s where the new drugs are being approved.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.