MONTREAL – If you think your ethnic-sounding last name is preventing you from finding a job in Quebec, you may be right.

Candidates called Tremblay or Morin are 64 per cent more likely to get an interview than someone with the same qualifications whose name is Ben Amin or Traoré, according to a study released Tuesday by the Quebec Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission.

A research assistant applied for 581 jobs from December 2010 to May 2011 under false names, half of them foreign-sounding and the other half typically francophone Québécois. Both types of fictional job-seekers had equivalent qualifications and had been educated in Quebec.

Nearly 40 per cent of candidates with francophone-sounding names, like Sébastien Bélanger, were offered an interview, compared to only 22.5 per cent of those with ethnic-sounding names, like Mahmoud El Kamal.

The study confirms what Quebec minorities have been saying for years: that job-market discrimination is widespread, said Fo Niemi, director of the Centre for Research-Action on Race Relations (CRARR).

“It shows there is a very strong racial bias out there,” Niemi said.

And without legal consequences for employers who discriminate against minorities, nothing much will change, Niemi said.

“Legal sanctions are the only way to force employers to be more fair,” he said.

The study shows that people with African-sounding names face the greatest discrimination. Candidates with francophone names were 72 per cent more likely to get an interview than those with African names, 63 per cent more likely than those with Arabic names, and 58 per cent more likely than those with Hispanic names.

Immigrants across Canada have higher rates of unemployment than native-born Canadians, but the gap is widest in Quebec, where 11.1 per cent of newcomers were unemployed in 2008, compared to 6.6 per cent of people born in the province, noted the report’s author, sociologist Paul Eid.

The employment gap between immigrants and non-immigrants is 4.5 per cent in Quebec, 1.4 per cent in Ontario and 0.4 per cent in British Columbia, he said.

The gap is particularly pronounced among university-educated black and Arab immigrants to Quebec, of whom more than 10 per cent are unemployed, compared to three per cent of native-born university grads.

Neither lack of recognition for foreign credentials nor lack of French-language skills explains that gap, since all of the fictitious candidates had acquired their education and job experience in Quebec, Eid said. For those educated abroad, unemployment barriers are even greater, he said.

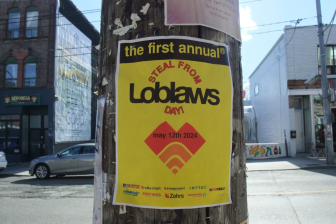

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

“Some employers look for employees who resemble them,” he said. “It might be because of fear of the unknown, mistrust towards foreigners or ignorance. And sometime it’s a mixture of those and racial prejudice.”

Commission president Gaétan Cousineau said job discrimination is the leading cause of complaints to the provincial rights body, accounting for 505 complaints in 2011-12, nearly half the total of 1,047.

“The advantage of this study is that it demonstrates that when (minority candidates) are not offered an interview, it is not just due to the fact that they were trained elsewhere and got their diplomas elsewhere. It’s also based on the origins of your name and on the perception that you come from elsewhere, even if you have been here for three or four generations,” he said.

Physical and mental disabilities were the top grounds of discrimination complaints to the commission (184 out of 505 complaints), followed by race and ethnic origin (115 complaints).

The report’s conclusions came as no surprise to Mohammed, 46, a senior manager in the public sector who had many doors slammed in his face during a two-year job search.

Mohammed, who emigrated from Morocco in 2004, did not want to reveal his name for fears of endangering his present job.

Mohammed said he tested the hypothesis that employers were rejecting him because of his origins by applying for jobs both under his real name and under a fictitious name, Jonathan Dubois.

Several private-sector employers offered “Dubois” an interview but ignored the application he submitted under his real name. (He did not pursue those applications further.)

In the end, Mohammed found a suitable job in the public sector.

“It was two years of hell,” he said. “Each time I read about somebody going through the same thing, it gets to me.”

The study found that minority candidates get a fair shake in the public sector – at least until the interview stage – landing interviews just as often as those with francophone names.

But in the private and non-profit sector, minority applicants face barriers both for unskilled and skilled jobs, it found.

For unskilled jobs, 46.4 per cent of applicants with francophone names were offered an interview, compared to 28.7 per cent with ethnic-sounding names. For skilled jobs, 30.2 per cent of francophone candidates got an interview, compared to 18.3 per cent of minority candidates.

While the employment gap for immigrants is higher in Quebec than other parts of Canada, some studies suggest immigrants face similar job discrimination in English Canada.

Last year, researchers Philip Oreopoulos and Diane Dechief sent out fictitious resumés in Toronto, Vancouver and to English-speaking employers in Montreal.

They found applicants with English-sounding names were 35 per cent more likely to receive callbacks than those with Indian or Chinese names.

Comments