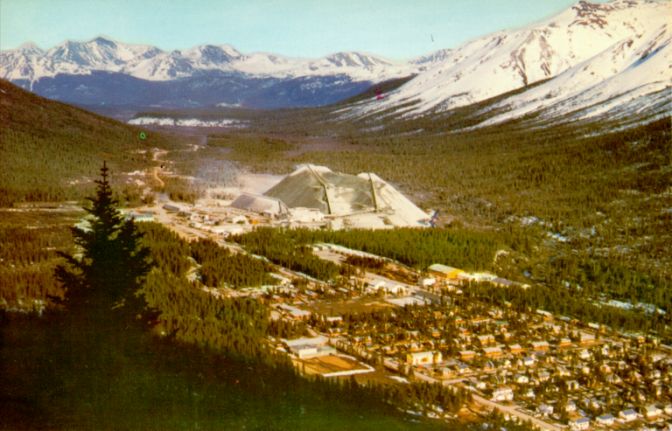

In the far north of British Columbia, hundreds of kilometres from any city, sits a ghost town less than 25 years old.

It’s estimated that around 5,000 people lived in Cassiar at one point in its 40-year history.

But if you can find the beaten road that leads to the abandoned site today, you’ll mostly see a valley where nature has reclaimed block after block of former homes.

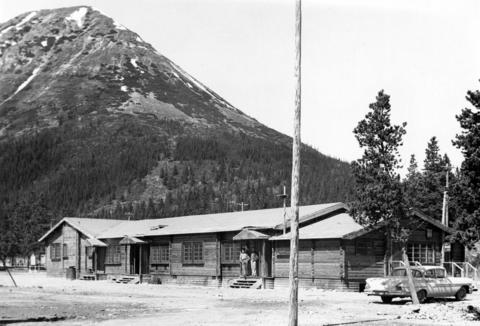

Still, there are signs of Cassiar’s past here, an ode to a time where small resource towns dotted and defined British Columbia’s rural landscape.

The giant mining site still sits, for starters. A few husks of destroyed buildings, slowly rotting away.

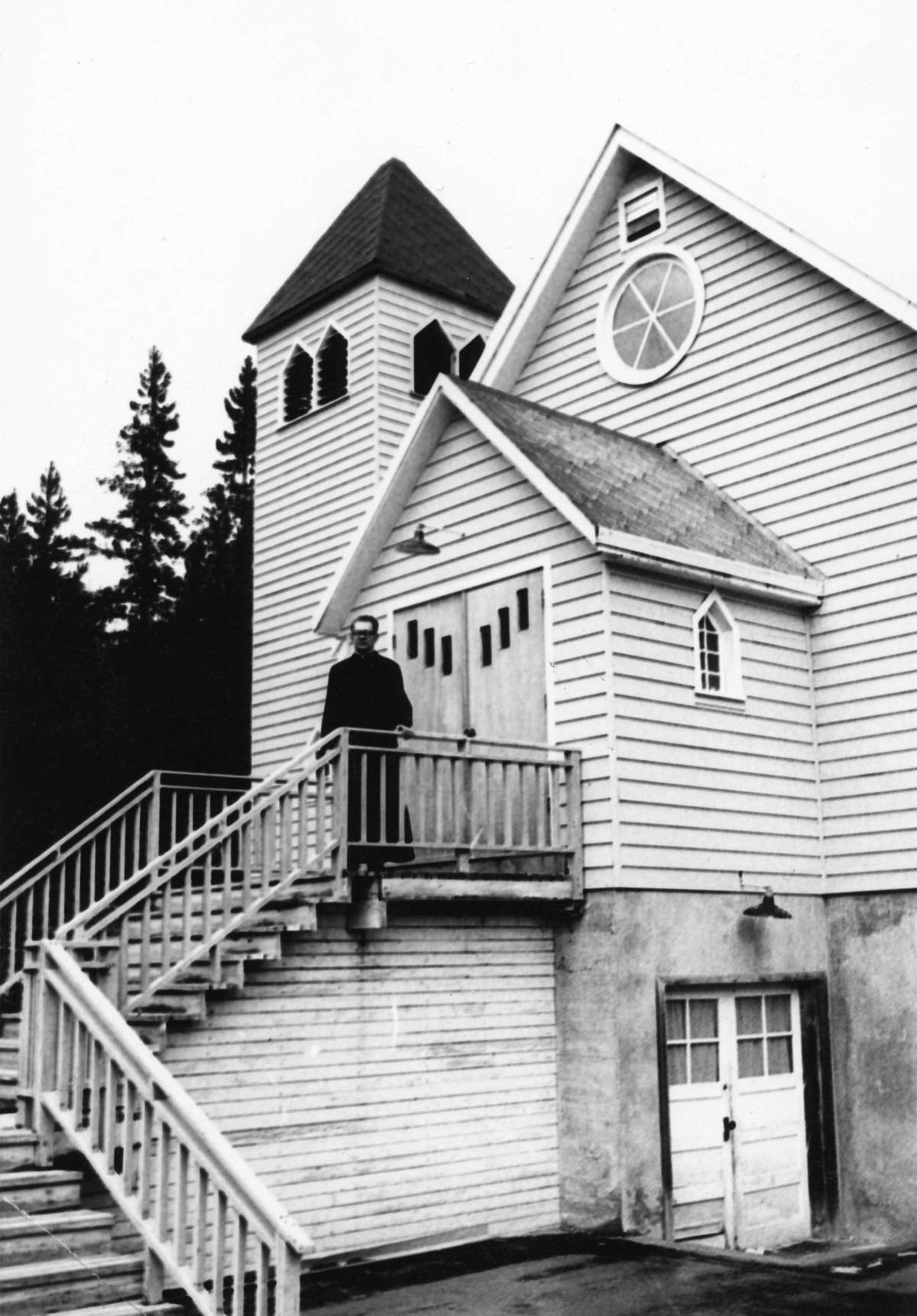

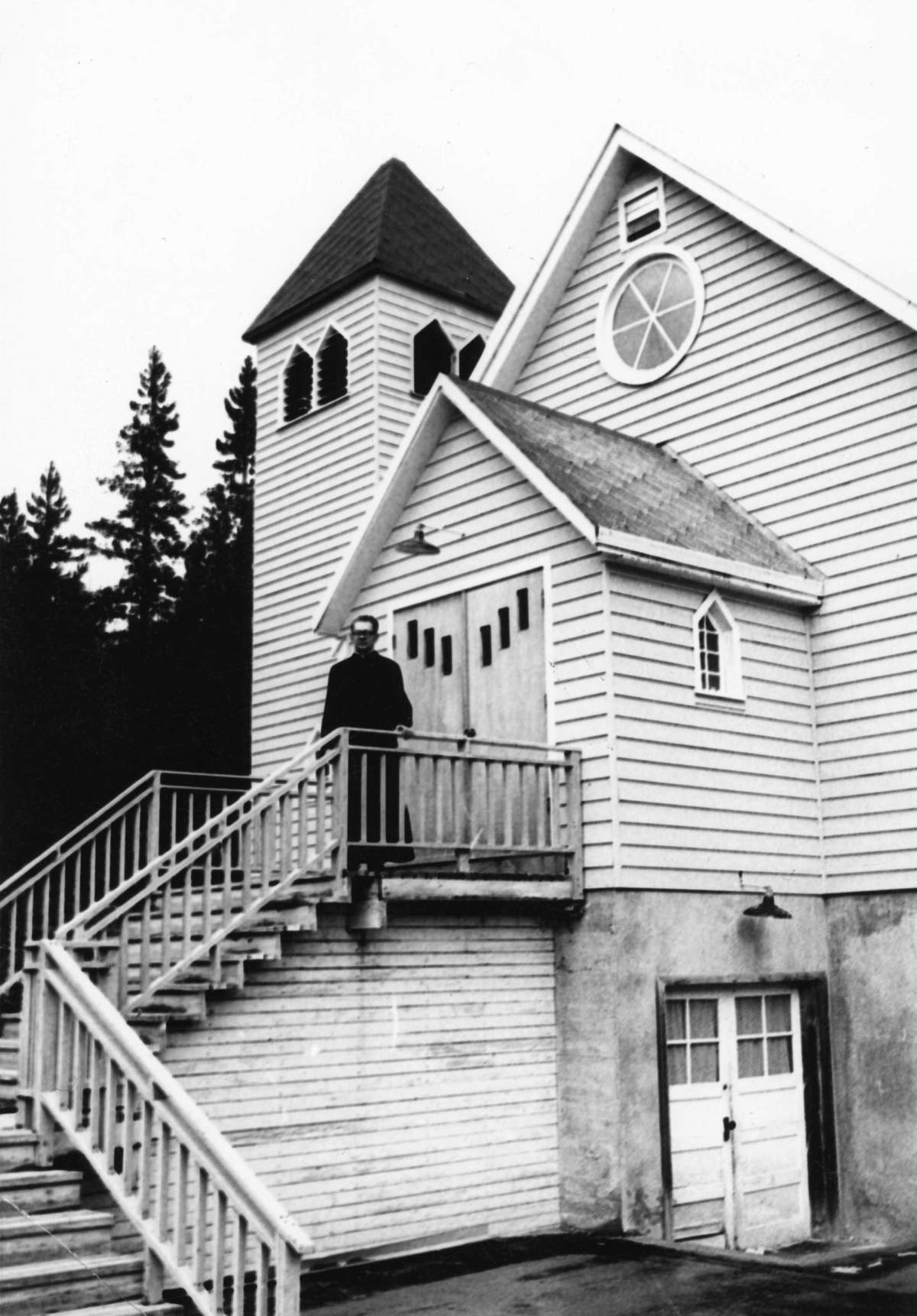

And, most curiously of all, a 50-foot tall church, still in fair condition.

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church served the community of Cassiar for over 30 years.

Today, it sits empty—the last cultural artifact of British Columbia’s last ghost town.

Herb Daum was one of the first people born in Cassiar.

“Winters were long and cold, the lakes didn’t ice out until June, and it could snow any day of the year,” he says, remembering his unique childhood in one of B.C.’s most isolated cities.

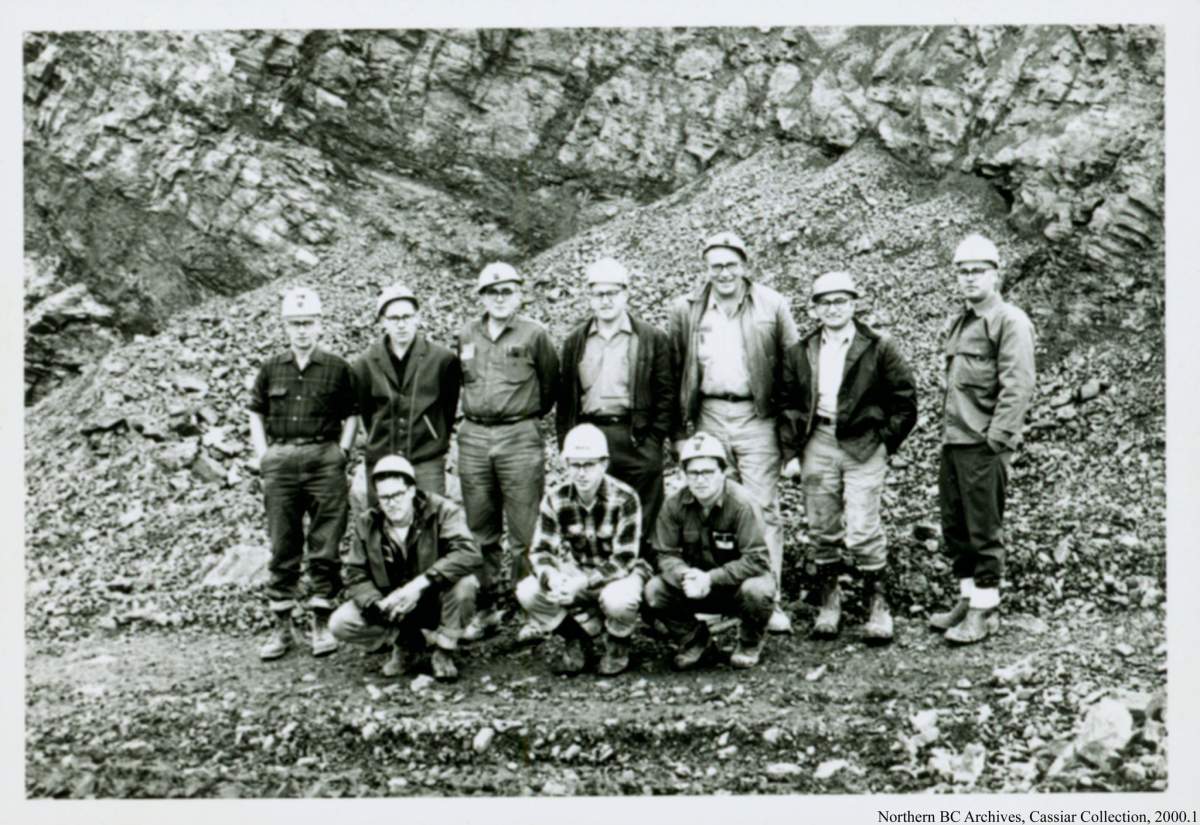

Daum was born in 1954, just two years after the Cassiar Asbestos Corporation began their open-pit mining operation.

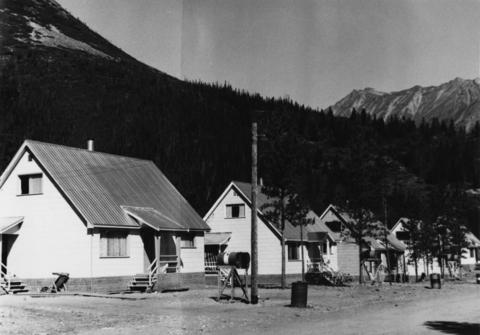

Like many one-resource communities in British Columbia, there was no local government, and the ruling company did everything they could to ensure employees would stay and raise their families.

“It was a full-blown town, and the reason for that was because of its isolation, the company was having trouble attracting people to work there,” said Daum. “High-rates of employee turnover made things expensive, they’re paying your travel in and out. They made a concentrated effort to develop it as a town, family friendly, and that made a big difference.”

There was a school. A hockey rink. A small hospital operated for a time by Bob Niedermayer, who had two young sons—future NHL stars Scott and Rob Niedermayer.

“A big deal was when we got a theatre,” says Daum.

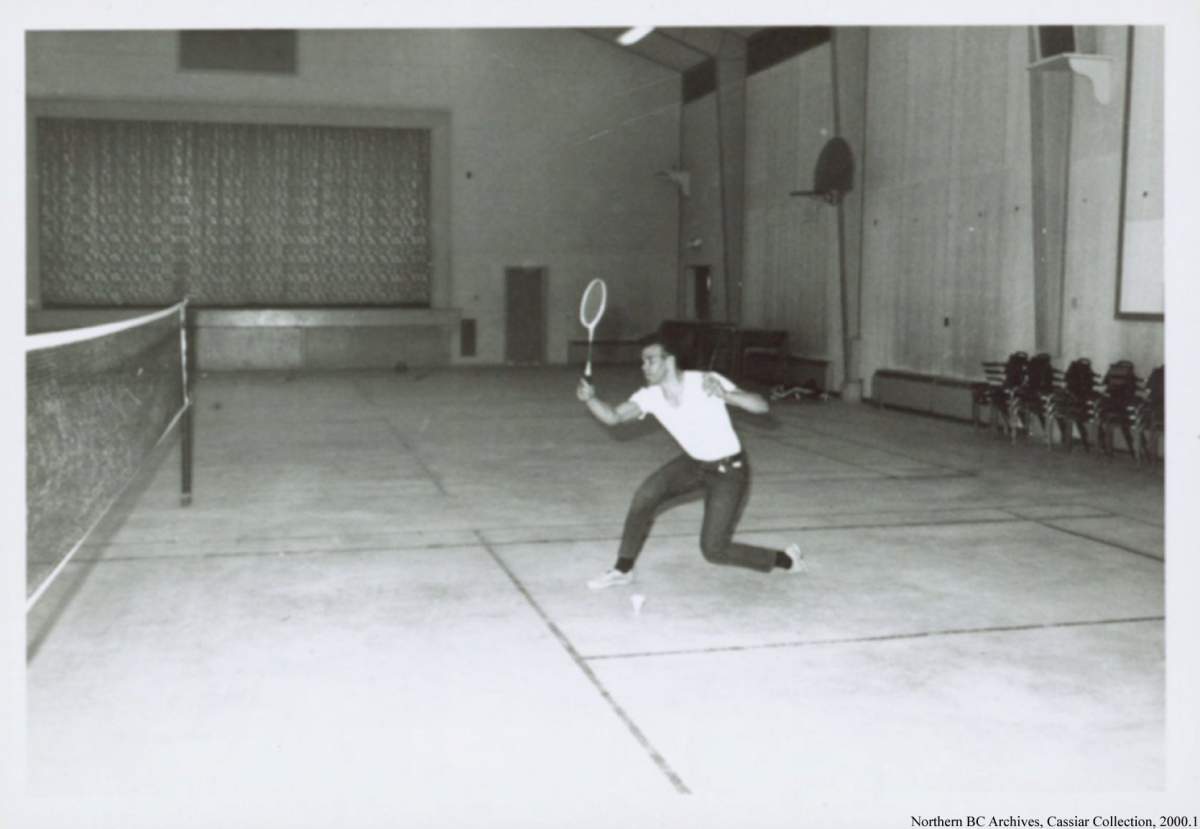

“Star Wars was the premiere. Before then we had the recreation centre, which had dual purposes. There was dancing, but the chairs could be set up for a movie on a projector. It cost 25 cents for kids, 75 cents for adults.”

GALLERY: Photos of Cassiar from 1952 to 1992 (All courtesy B.C. Archives)

Cassiar’s business of asbestos flourished, with their product even used on NASA space capsules. However, the isolation could be a challenge for the 2,000 or so people who called Cassiar home, and trips to large cities were rare and expensive.

“Originally most of the labour pool was men, there was very few women,” said Daum.

Get breaking National news

“It was pretty bleak if you were on the male side of the spectrum.”

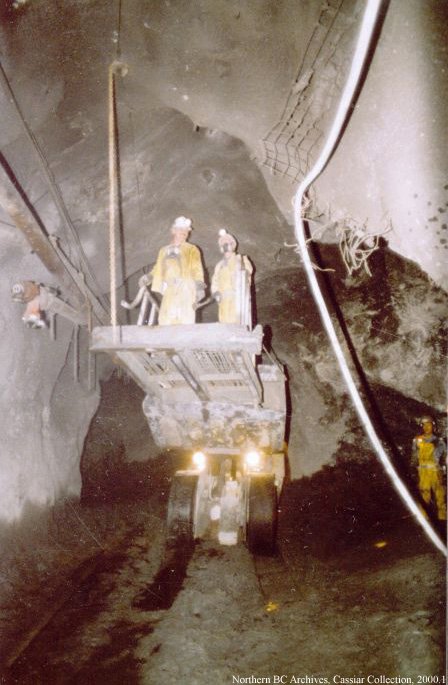

Daum left in the mid-80’s—”I had enough of the ice and the snow,” he quipped—and within a few years, the asbestos industry as a whole began to significantly decline. An attempt to convert mining operations below ground was disastrous, and creditors refused to restructure the town’s significant debts.

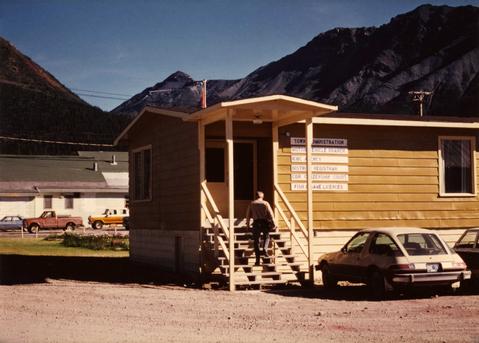

In early 1992, the mine shut down and the company went into receivership. With no takers, the provincial government initiated an auction of Cassiar’s assets seven months later.

After 40 years, Cassiar was no more.

WATCH: A BCTV story from 1992 when Cassiar was abandoned and auctioned off

Cassiar was sold off piece by piece over five days in September of 1992. Over 5,000 lots were purchased, raising $6 million that went to various creditors. From mining infrastructure to homes, commercial stores to school equipment, virtually everything was sent away.

But a few things stayed—including a certain church.

“I’ve been to a few funerals there, a few weddings,” Valdemar Isidoro told the Terrace Standard days after he purchased the church for $650.

“I wanted the bell, but the bishop had already taken it to Whitehorse.”

The provincial government expected everyone who purchased buildings to ship them away or tear them apart for pieces that could be re-used in new buildings.

Isidoro, an equipment operator in town for 25 years, decided to keep the church in Cassiar.

“Sentimental reasons,” he says today from his home in the Okanagan.

“I bought it for $650, could have sold it for $3000…but I never thought of moving it.”

In the years since, as Cassiar has faded from memory, so too have its physical remnants. A fire burned down the mill in 2000. The hockey arena collapsed in 2008.

The town is now little more than the old mining pit, and two apartment buildings that surveyors occasionally use as a base to explore the region.

Digitally, the town survives. Through Daum’s Facebook group Cassiar…do you Remember? and occasional reunions, the thousands of people who called Cassiar home have a place to reconnect and reminisce.

“It’s wonderful. Been life-changing. We used to have a message board, and one of my former bosses, he said he found it before bed, and at 5 a.m. was still reading all these messages,” said Daum.

“People get hooked into it. It’s been amazing for so many people to reconnect.”

Still, there’s little nostalgia in the memories.

“It’s in the past. Creating a life there, building a life there would be challenging without a lot of resources,” says Daum, who keeps a rock of asbestos among his artifacts from the town.

“What would you live on? There’s no agriculture. I think for most it’s a chapter in your life that’s kept open with fond memories. I’m sure I could, but I don’t have a strong interest to go back and see the place.”

“Sad memories,” says Isidoro, who also has no intention of returning.

“It’s a sad place to visit, after all those years.”

GALLERY: Photos of Cassiar since 1992 (All courtesy the Cassiar…do you Remember? Facebook page

If there’s any potential for a physical monument to remember Cassiar, it’s the town church.

“Some of the floor is starting to rot, but the foundation is still good,” says Isidoro.

“It’s an aluminium roof, and riding was put on a year or two beforehand.”

Still, he says he doesn’t have the means to relocate or refurbish the building—and because of a strange quirk in how heritage buildings are designated in British Columbia, it might continue to deteriorate.

A spokesperson for the BC Heritage Branch told Global News that heritage buildings are almost never chosen at a provincial level, instead falling to local governments or regional districts to nominate sites and raise funds.

But there are no people in Cassiar. And the area is part of the sparsely populated Stikine Region—the only part of British Columbia not to have a regional district.

“It’s a bit of a loophole,” the spokesperson admitted.

Which means that unless the provincial government takes initiative, the church is slightly to continue to sit. Slowly decaying. Perhaps destined to become mere history like the rest of Cassiar.

But for now, it holds the memories of those who once called this town home.

Postscript: This story was originally written and researched in late 2015. In the time since, the church has burnt down, a former resident of Cassiar has told Global News.

WATCH: Drone footage of Cassiar, taken by former resident Gordon Loverin in 2015

“Ghost Town Mysteries” is a semi-regular online series exploring some of the strange sights from B.C.’s past.

The old trolley buses of Sandon

The swimming pool of Mount Sheer

The stolen lightbulbs of Anyox

The 30-year slumber of Kitsault

The international interest in Bradian

The cenotaph of Phoenix

Can Sandon be saved?

Comments