Tamara Dalrymple gets all kinds of people.

Athletes, musicians who want to improve their performance. People with low energy or anxiety or who have trouble concentrating.

And people whose scarring memories have made their lives hell.

READ MORE: Canada still falls short in treating soldiers’ psychic scars

“It’s kind of amazing,” she said.

“Different things might respond at different times.”

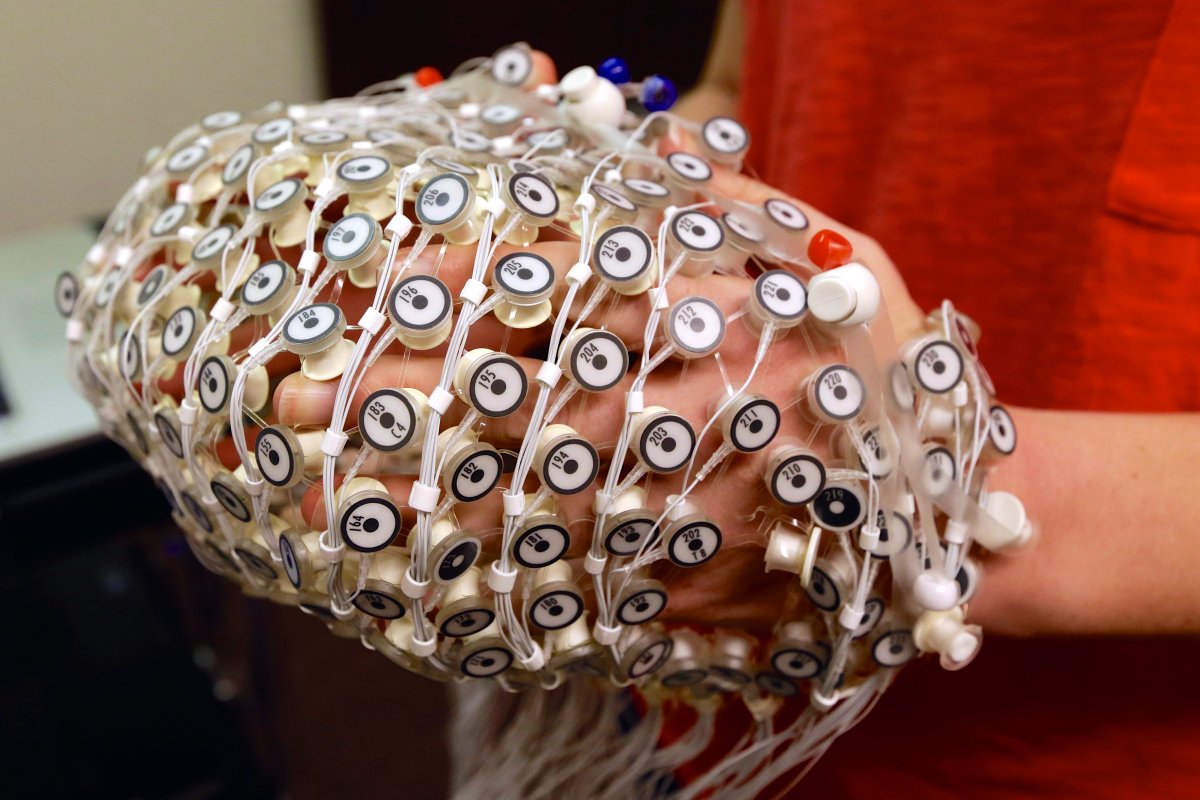

Dalrymple is a certified neurofeedback practitioner, using sci-fi sounding therapy and scalp-hugging sensors to measure and retrain brainwaves using sound-based feedback and an electroencephalogram.

The sensors and EEG figure out what parts of your brain are over-active, or not active enough. Headphones programmed to play different sounds depending on your brain wave activity train your brain to use healthier, calmer or more “optimal” patterns.

“You can kind of watch as the brain starts to adjust to the training parameters,” she said.

Dalrymple works with Stephan Moreau, a former Canadian Forces seaman working through his PTSD.

He also used neurofeedback therapy after a bad wipeout on his bike last summer.

“It’s something I had to reach out for. [Veterans Affairs] didn’t call me and say, ‘Do you want to try neurofeedback?'”

“It’s one of those things that you have to kind of believe in it for it to work. You need to be sort of open-minded about it.”

READ MORE: Veterans Affairs Minister vows to change the way Canada treats vets

Neurofeedback is one of the less strenuously tested treatments out there for post-traumatic stress disorder, says Ruth Lanius, director of the University of Western Ontario’s PTSD research unit.

Get weekly health news

“We’re starting to get evidence for neurofeedback as a brain-based intervention for post traumatic stress disorder,” she said.

Lanius has seen “some very promising data” brought forward recently backing up the use of neurofeedback.

“Neurofeedback really seems to bring online areas involved in emotion regulation,” she said.

“It’s a promising adjunct treatment” — something best used in combination with other forms of therapy.

“The strongest evidence base right now is cognitive behavioural therapy as well as EMDR.”

EMDR

That stands for “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing,” which rests on the premise that psychological pathologies such as PTSD are the result of your brain’s maladaptive encoding or processing of traumatic events.

The idea behind this treatment is to reprogram those memories so your brain can cope better.

“In the broadest sense, EMDR is an integrative psychotherapy approach intended to treat psychological disorders, to alleviate human suffering and to assist individuals to fulfill their potential for development, while minimizing risks of harm in its application,” reads the EMDR International Association’s definition.

“Its really based on what’s called ‘free association,'” Lanius said.

“You may ask the person to bring up a traumatic memory, then whatever the person brings up during the therapy — which may not be related to the trauma that you started with — you let the person go with that and sort of reprocess the traumatic event with whatever the mind brings.”

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

CBT is commonly used for myriad mental illnesses.

“With CBT, you do a lot of cognitive restructuring exposure work directly focused on a specific trauma,” Lanius said.

It focuses much more on logical or rational dissection of thoughts associated with traumatic events.

“You really focus on one memory at a time,” Lanius said.

“And you don’t do the free association that is part of EMDR.”

Some people get better after 10 or 12 sessions of therapy, Lanius said. Others take far longer.

And concurrent disorders, including depression and substance abuse, can make recovery far more challenging.

“Both CBT and EMDR have a strong evidence base,” Lanius said.

“Something we really have to think about in the future is personalized medicine … really figuring out who is best suited to what kind of treatment.”

But she thinks the military’s getting better at understanding the importance of treating trauma.

“I think the military has done a great deal to educate people about PTSD and to reduce the stigma,” she said.

“I think some people still feel this is all in your head and that it’s very different from a physical injury.

“It’s actually very similar but the injury is hidden in the brain.”

READ MORE: Army suicide rate 3 times higher than other branches of Canadian Forces

Comments