A geography professor from the University of Victoria (UVIC) in British Columbia says people living along low-lying sections of the province’s coast should prepare themselves for the arrival of an El Niño event.

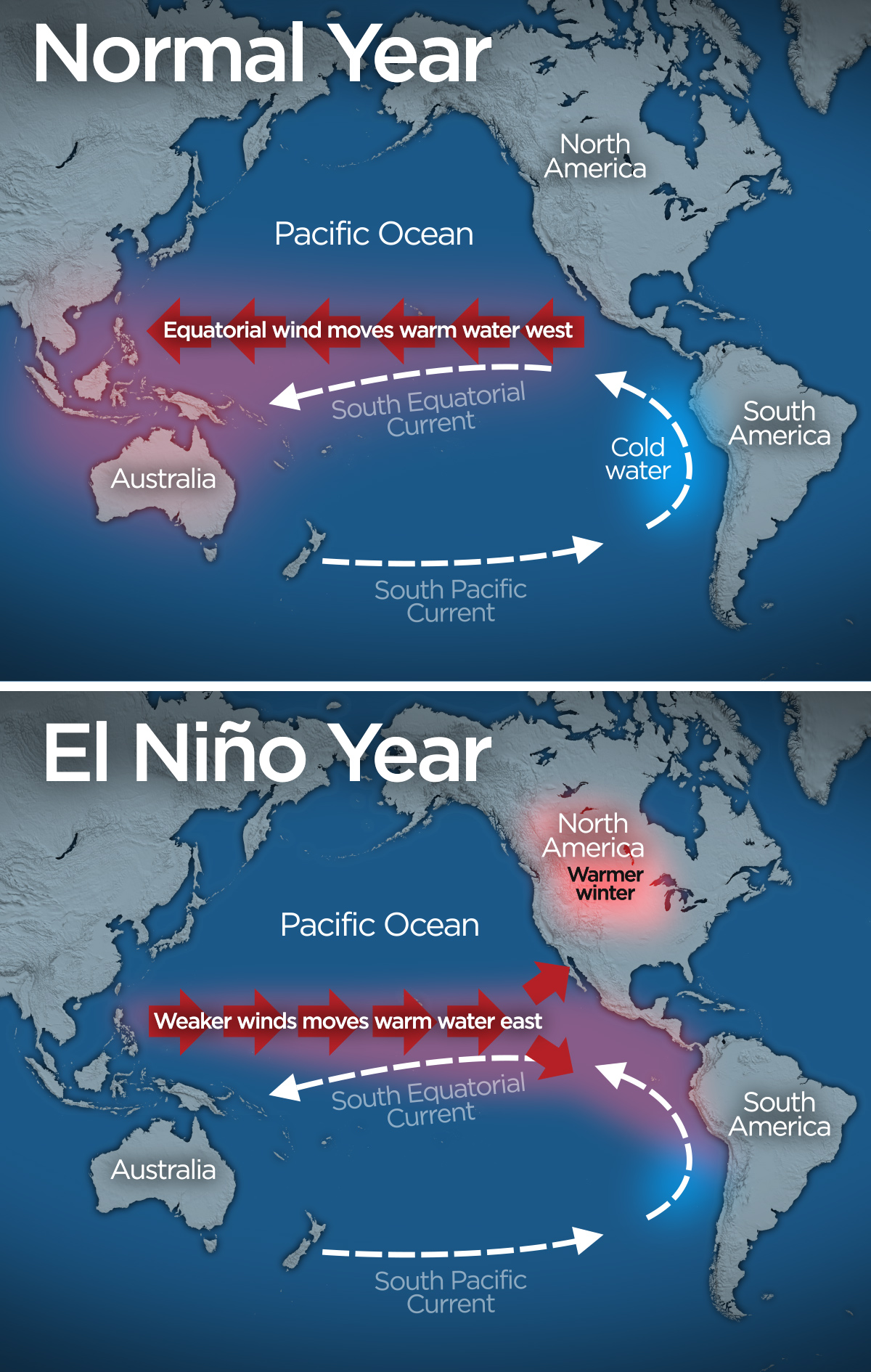

El Niño is a natural, tropical, ocean temperature phenomenon.

Warm water in the Pacific near the equator moves towards the north coast of South America and deflects northward, as far as Haida Gwaii and Alaska.

READ MORE: Could a rare ‘Double El Niño’ lead to record high temperatures in B.C.?

Professor Ian Walker at UVIC says this year will be an El Niño year, probably the largest ever witnessed.

He says past El Niños that have hit between B.C. and California have resulted in some of the highest historic rates of erosion, so British Columbians should prepare.

“We’ve been watching this through what’s called ‘the El Niño index’ and it’s a bunch of measurements across the Pacific that indicate whether we’re in an El Niño or a warm phase, which means warmer coastal currents for the coast of British Columbia down to California,” says Walker. “Or the opposite, a cooler La Niña phase, and we’re definitely ramping up to be one of the most significant events.”

Walker was among a group of 13 researchers from universities and government agencies who tried to determine if patterns in coastal change, such as erosion and flooding, could be connected to major climate cycles, like El Niño and La Niña, across the Pacific.

Get daily National news

Their work was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“It’s not just El Niño we should be concerned about,” says Walker. “Our research shows that severe coastal erosion and flooding can occur along the British Columbia coast during both El Niño and La Niña storm seasons unlike further south in California. We need to prepare not only for this winter, but also what could follow when La Niña comes.”

He says we could also see elevated ocean levels, meaning that the average winter storm could cause more damage due to the higher sea levels. And then during the La Niña year, there will be more storms and strong winds, which lead to flooding and erosion on the coast.

WATCH: Global’s chief meteorologist Anthony Farnell tells us everything you need to know about El Niño

“With average storm conditions, that elevation is just enough to put it to an erosional or flooding level,” adds Walker. “So imagine all these low-lying beaches or eroding bluffs, like at Point Grey or Wreck Beach, for example, that normally see during big high tides, water levels that can get close enough to cause erosion, there’s a greater chance of that happening in this season.”

What will the weather look like across B.C.?

Matt MacDonald, a meteorologist with Environment Canada, confirms this year will have the strongest El Niño on record. “But it’s important to point out, the records only go back to 1950,” he says. “So in the past 65 years, yes it’s the strongest. The previous strongest was actually 97/98 and we’re exceeding that strength so we’re expecting quite a strong Niño heading into this winter.”

The following year, 98/99, was a record-breaking snowfall year for many locations on the west coast.

MacDonald says it means the weather will be about 10 per cent drier than normal and warmer than normal conditions – about two to three degrees warmer than normal.

“A lot of people get excited about El Niño and there’s been a lot of hype this year with this extreme El Niño, the Godzilla El Niño or even the Bruce Lee El Niño, but what can we really say here on the west coast? Simply warmer than normal and slightly drier than normal.”

Drier than normal conditions will be what residents on the South Coast will experience, while the northern half of the province will see about 10 per cent more rainfall than normal. “Really, in terms of temperature, it’s the same effect all across Canada,” says MacDonald. “We can expect a warmer than normal winter.”

The effects of El Niño are not typically felt until the middle of January so B.C. may get colder than normal temperatures before that. However, MacDonald says B.C. should see a warmer-than-normal fall.

Walker says what is important is what is happening in the oceans, not what is happening in the atmosphere. “The same storms that hit us, on average every winter, on a higher ocean level will be causing more damage.”

– With files from The Canadian Press

Comments