Whoever becomes Canada’s next prime minister will have to figure out how health practitioners help suffering people die.

After Feb. 6, 2016, the part of Canada’s Criminal Code making physician-assisted death illegal will become null and void.

February will mark a year since the Supreme Court’s landmark unanimous decision striking down Canada’s prohibition on assisted suicide.

The court gave Ottawa a year’s grace to come up with new laws governing how health care practitioners should deal with patients enduring extreme suffering who want to end their lives.

But no new laws have been forthcoming: The federal government announced a panel in July to consult the public on the issue, but it was criticized for featuring experts who’d been paid to testify against physician-assisted death, and many argued it was too little, too late.

WATCH: Doctors call on government for legislative response to assisted suicide

“I am deeply disappointed by the Conservative party position — they followed months of inaction with active obstruction,” said Wanda Morris, CEO of Dying With Dignity Canada, a group advocating for physician-assisted death.

“Not only did they create a panel comprised of two of three people that actively oppose assisted dying, they then released a consultation process with questions designed to manufacture fear.”

Morris noted that public opinion polls have indicated all voters, including Conservative supporters, support physician-assisted death as an option for people in pain.

“I feel bad for these voters being let down by their government.”

Neither the Conservatives nor the NDP responded to Global News’ requests for comment this week.

Liberal spokesperson Cameron Ahmad said the Liberals would make a non-partisan committee consultation a priority if the party forms government, noting Liberal leader Justin Trudeau tried to do that several months ago only to be blocked by the Conservatives.

“We recognize the sensitivity of the issue. We recognize the fact that this affects families and people’s lives directly,” he said.

“Now we’re running out of time, and we’re unfortunately reaching that deadline without much progress having been made.”

Ahmad couldn’t say how that committee would deal with the pending February deadline, however.

Get weekly health news

Whatever happens, there are plenty of unanswered questions. And in the absence of federal action, several other groups have stepped in to try and fill the gaps.

The Canadian Medical Association has been talking with its members for almost two years about how to deal with physician-assisted death. Its most recent report wrestles with the balance between patient rights to care and physicians’ rights not to participate in a patient’s death, and the need to educate physicians about how to approach the issue, period.

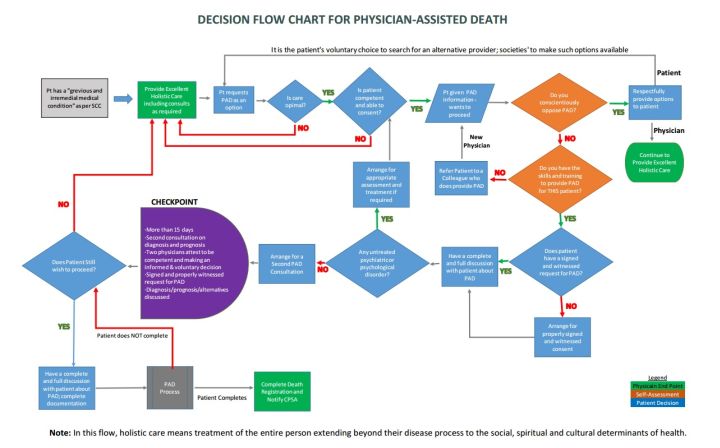

Alberta’s College of Physicians and Surgeons has put together recommendations for its members and sought feedback on them and on a flowchart that includes suggested courses of action for health care practitioners dealing with patients who want to die.

A provincial-territorial expert panel starts its work this week, hammering out advice to governments on how to regulate physician-assisted death.

“Each province and territory then would take those and say, ‘What does this mean for our jurisdiction?'” said Jennifer Gibson, the panel’s co-chair and head of the University of Toronto’s Joint Centre for Bioethics.

“Assuming that, on Feb. 6, it is not illegal, how do we put this into practice?”

WATCH: Ontario government creates advisory group to study physician-assisted suicide

Here are some of the questions they’re wrestling with:

What counts as a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” that causes “intolerable” suffering?

In stark contrast to jurisdictions such as Washington and Oregon, the Supreme Court’s ruling didn’t restrict the right to assisted suicide to people with terminal illness who are facing imminent death anyway. This decision opens the door to any competent adult with any “grievous and irremediable” medical condition, including mental illness, as long as they’re still able to make decisions for themselves.

So how do you define “grievous and irremediable”? Or do you even need to — is it enough for a person to believe she’s suffering horribly?

“It is an open question, how much we then need to define explicitly, in guidelines or legislation, what each of those terms mean,” Gibson said.

What happens when doctors don’t want to help someone die?

No one wants to force a doctor or other health-care practitioner to help kill someone who wants to die if doing so is against that person’s religious or ethical beliefs. But how do you ensure that a sick person who wants help dying gets the care he needs? Would you require physicians who object to assisted suicide to refer patients to someone willing to help them? How do you provide for people living in remote or rural communities where alternative health care isn’t available?

“How will we respond to these differences in conscience without shutting people down?” Gibson asked.

“How we think about conscience also has implications for access. … If you are one of the few providers in that community, where would those individuals go?”

How do the new rules apply to other health care practitioners?

The term “physician-assisted death” can be misleading: Helping sick people die often involves many other actors, including pharmacists dispensing lethal prescriptions or hospices housing people who want to die. How do you protect those people from prosecution? What do you do if, for example, a person wants to die and a doctor is willing to help her but the hospice where she lives isn’t willing to host the procedure?

“What are the roles of other regulated health professionals?” Gibson said.

“What implementation challenges or questions need to be answered, what are the resources and supports that health professionals might need in order to be able to provide this service?”

Gibson, for her part, wishes the federal parties and their leaders would keep the issue in mind as they jostle for votes over the next several weeks.

“This is going to affect all of us,” she said.

“Just acknowledging that this is here, providing some clarity, gives me confidence, as a voter, about what their position might be.”

Whatever the next government’s political stripe, this is something they’ll have to deal with, Gibson notes. So it’d be nice to know where they stand before Oct. 19.

“They should not be silent,” she said.

“The party that gets elected … whoever they might be, this is going to be on their plate. And on the day after the election, people are still going to have to go to work. They’re still going to have to care for their families. They’re still going to be faced with end-of-life decisions.”

Comments