Perhaps you’ve noticed: The economy’s a big deal in this federal election.

The party leaders have repeated their middle-class mantras and job-creation buzzwords from one supporter-packed podium to another.

Here are a few things to keep in mind about the economy, a key election issue:

Economy’s okay, but not best in the G7

This country weathered the recession relatively well, compared to other countries in its peer group. But Canada’s not much better off than everyone else: We’re middle of the pack, Ivey School of Business economist Mike Moffatt says.

And as commodity prices swooned this year, the immediate growth outlook isn’t all that pretty.

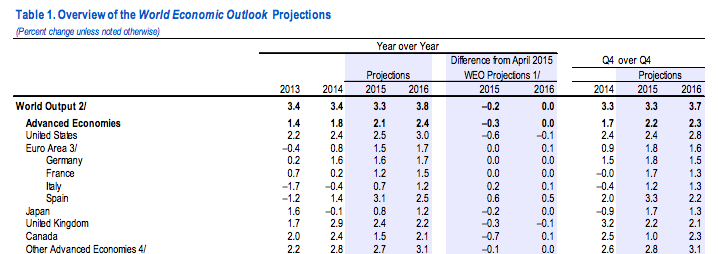

Here’s the International Monetary Fund’s July projections:

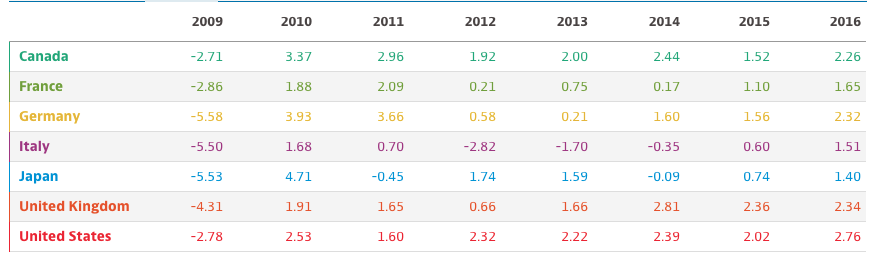

And here’s how Canada stacks up according to the OECD:

Unemployment’s down, but still higher than pre-recession

Overall, Canada’s unemployment rate is still higher than it was before the recession: 6.9 per cent, compared with 6.0 in 2007 and 6.1 in 2008.

Almost all provincial unemployment rates have dropped since 2009, however — save for New Brunswick and Manitoba.

Interactive: Hover or tap for details

Provinces with a higher unemployment rate than pre-recession:

- B.C.

- Alberta

- Manitoba

- Ontario

- Quebec

- New Brunswick

- Nova Scotia

- PEI

Provinces with lower unemployment than pre-recession:

- Saskatchewan

- Newfoundland

Tough times for youth jobs

It’s not just millennial whining: Young people are having a harder time in the job market, and haven’t seen as much of a recovery post-recession as their older counterparts.

Participation rates and employment rates for young people have dropped, which is worrisome: It means more people are simply giving up looking for work.

The employment rate for people aged 25-29 is down two percentage points since 2006, from 80 to 78. For 15-to-24-year-olds, it’s down from 54 to 52 per cent.

Interactive: Hover or tap for details

“Young people are the only category of Canadians that have seen no recovery,” said Armine Yalnizyan, a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

“They’re just dropping out. And a growing contingent is not in work or school.”

Get weekly money news

In the short term, this is bad news for an economy that relies heavily on consumer spending.

But if people are unemployed or under-employed for extended periods of time, skills atrophy and contacts go stale and the labour market suffers.

“We’re looking at, potentially, a long-term scarring effect,” Yalnizyan said.

The Tories’ promised apprenticeship grant expansion could help with that, if it gets more young people into entry-level positions in sectors that need skills.

“There are skills shortages, so incenting people to go into those areas can make sense,” says Moffatt, who’s also chief economist at the Mowat Centre and was on Liberal leader Justin Trudeau’s economic advisory panel along with George Gosbee, former adviser to Tory Financial Minister Jim Flaherty .

But “the devil’s in the details”: You’d need to ensure the people who enter apprenticeships actually stay employed and in the job market, and that apprentices don’t simply replace full-salaried workers.

Most unemployed Canadians aren’t getting EI

Employment Insurance covers fewer than four in 10 unemployed Canadians — and coverage varies widely depending where you live.

While 88 per cent of PEI residents out of work in May qualified for EI, only 28 per cent of unemployed Ontarians did.

Interactive: Hover or tap for details

There are vastly different rules around who qualifies for EI between Canada’s 56 different EI regions.

“Because so many of the unemployed are not eligible for EI, they are also ineligible to receive Employment Benefits, which are the interventions most likely to lead to re-employment,” Allison Bramwell wrote in a paper for the Mowat Centre.

“If this policy gap widens, those who fall through the cracks will fall further and further behind.”

The CCPA’s David Macdonald argues that’s unfair at the best of times, but particularly when precarious and part-time employment become the norm.

“The working poor can’t access EI at all,” he said.

“A fairer system would be a simpler system where it doesn’t matter if you live on this side of a dividing line or that side, you get the same benefits.”

Income’s up, but not by much

Inflation-adjusted median income is up since the recession, but it hasn’t grown by much. And even though women saw more income growth than men, there’s still a significant gender gap:

Sexy politics, iffy economics

If you were planning on renovating your man cave or upgrading your reading grotto two years from now, the Tories’ promise to renew the Home Renovation Tax Credit in 2017 would have come as welcome news.

But there isn’t much of an economic argument for it, Moffatt said.

“Economically, it’s hard to say what the purpose of it is.”

The 2009 iteration of the home renovation tax credit made sense: “It was a recession and you had all the out-of-work construction workers: You not only stimulated the economy, but you got people back to work.

“Neither of those things are the case if you make this thing permanent.”

And while much of Canada’s economy appears to have hit turbulence, the housing sector is hardly one of them: If anything, it’s overheated.

“Residential real estate is one part of the economy that’s done really well lately,” Moffatt said.

“It’s not obvious what the market failure is. It’s not clear why the taxpayer should give me an incentive to change my countertops.”

Fixing poverty is more complicated than raising the minimum wage

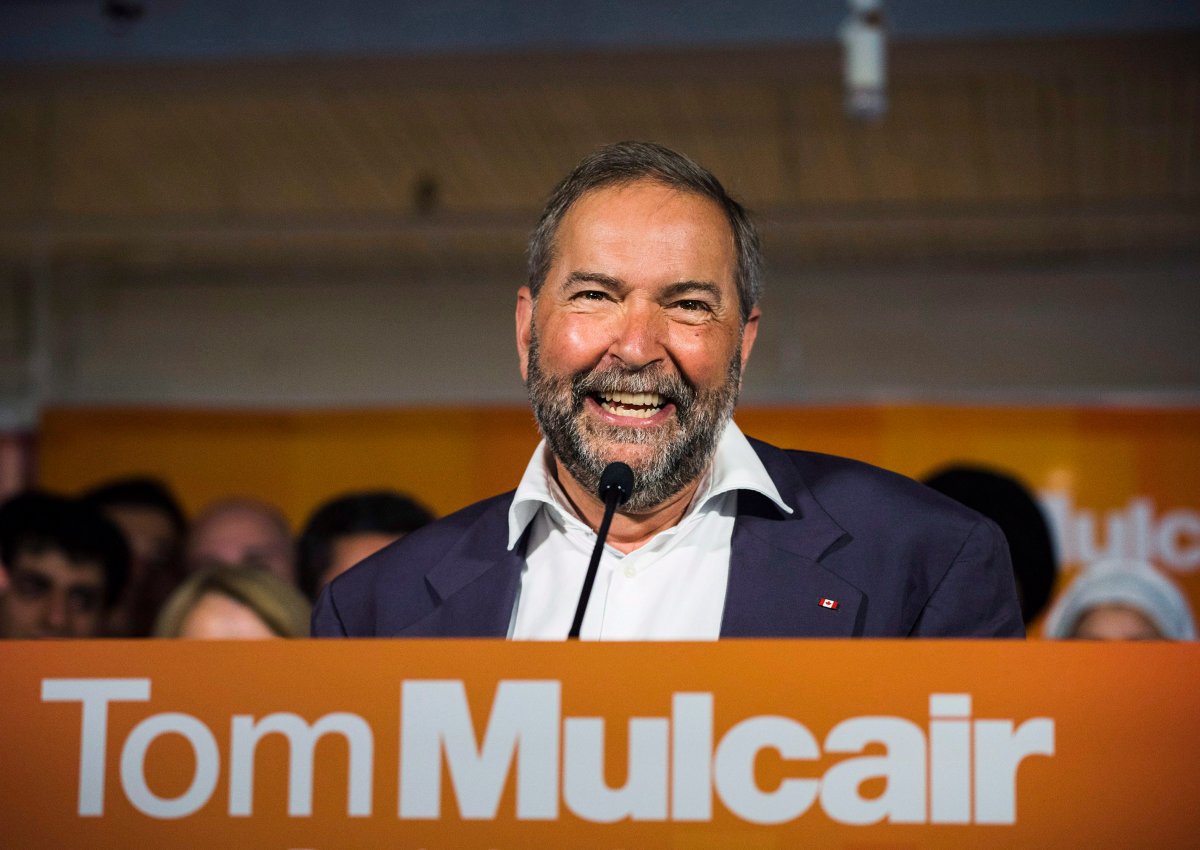

NDP leader Thomas Mulcair made headlines with his proposed $15 minimum wage for federally regulated workers.

He also left people scratching their heads: Whom would this affect, exactly?

Tough to say: The term “federally regulated” is broad and covers a vast swath of sectors and industries. There’s no easy way of assessing exactly how many people in federally regulated jobs are making less than $15 an hour.

READ MORE: Reality check – Does the NDP minimum wage plan leave out 99% of minimum wage earners?

“The issue is really confusing to a lot of people: Nobody really knows who is or who isn’t a federally regulated worker,” Moffatt said. “That’s not to suggest that’s a bad plan, but it is a difficult one to sort of explain to the average voter.”

So why didn’t Mulcair save everyone the headache and impose a $15 minimum wage across the board?

Because he can’t.

“Those rules fall under provincial jurisdiction,” Moffatt said.

“He couldn’t offer a $15 minimum wage across the board if he wanted to.”

The percentage of Canadians earning minimum wage or less has risen from 4 per cent in 2002 to 7 per cent in 2014:

And there’s significant variation from province to province:

But hiking the minimum wage isn’t necessarily the best way to go if your real target is eliminating poverty: Wages and incomes are not the same thing.

“Economically it’s not the best tool to raise the standard of living: You get a lot of people who are low income, but don’t earn minimum wage.”

While many have argued for a guaranteed income supplement or an expanded Working Income Tax Benefit, which would top up lower incomes, that can get expensive.

“In one sense what the Liberals are doing with their child benefit is one form of a guaranteed annual income”: It tops up the incomes of poor families with young children.

The Trans-Pacific elephant in the room

The federal government hoped to have the Trans-Pacific Partnership signed, sealed and delivered before it kicked off this election campaign.

But after talks broke down last week, the government finds itself in the uncomfortable position of running for re-election while negotiating a huge, complex multilateral trade deal.

“It’s sort of unavoidable. I mean, this is a large international thing and they’re not going to dictate this negotiation by Canada’s schedule,” Moffatt said.

“But … it does put the government in a very awkward position.”

It becomes a tricky accountability issue to navigate, as bits of the ostensibly secret negotiations are leaked.

Yalnizyan argues there hasn’t been enough scrutiny on the impact the TPP negotiations will have on job security and workers’ rights.

“You’ve got one sitting government that’s reapplying for the for the job and may not get it. So if they sign and ratify a deal … what does it mean for the next government?”

Comments