WATCH: Mark McAllister investigates the lack of diversity within Toronto Fire Services.

It’s safe to say it wasn’t the intended message.

It was budget season for Toronto’s city council, in January of 2013, and lots of groups had skin in the game and turf to defend.

One was the city’s firefighters, dozens of whom showed up at the council chambers in red union T-shirts to protest a plan to take five trucks off the road and close a west-end fire station.

“The firefighters came in, and they were protesting the reduction in stations and apparatus,” remembers councillor Michael Thompson. “And I looked at the audience – in fact, I took a picture of the audience.”

Thompson, who is black, had been hearing from black constituents who felt that their applications to join the fire department hadn’t been treated fairly.

“When I looked at the audience, there was nobody there that reflected the Toronto that has the 50 per cent that is racially diverse,” he says, delicately.

Firefighting is demanding and sometimes dangerous, but firefighting jobs are secure and well-paid, and there has never been any shortage of applicants. Toronto firefighters have a baseline salary of about $90,000, but most make over $100,000, Ontario salary disclosure data shows.

- S&P/TSX composite down, U.S. markets mixed ahead of tech earnings and economic data

- Big warm-up to follow blast of cold air in southern Ontario

- 1 deal falls through but Toronto FC completes another in Derrick Etienne Jr. trade

- No more sick notes? Why the Ford government wants to eliminate doctors notes for illness

In 2012, 2,408 people applied to the Toronto department, which has about 2,700 firefighters. Toronto firefighters leave the department almost entirely through retirement.

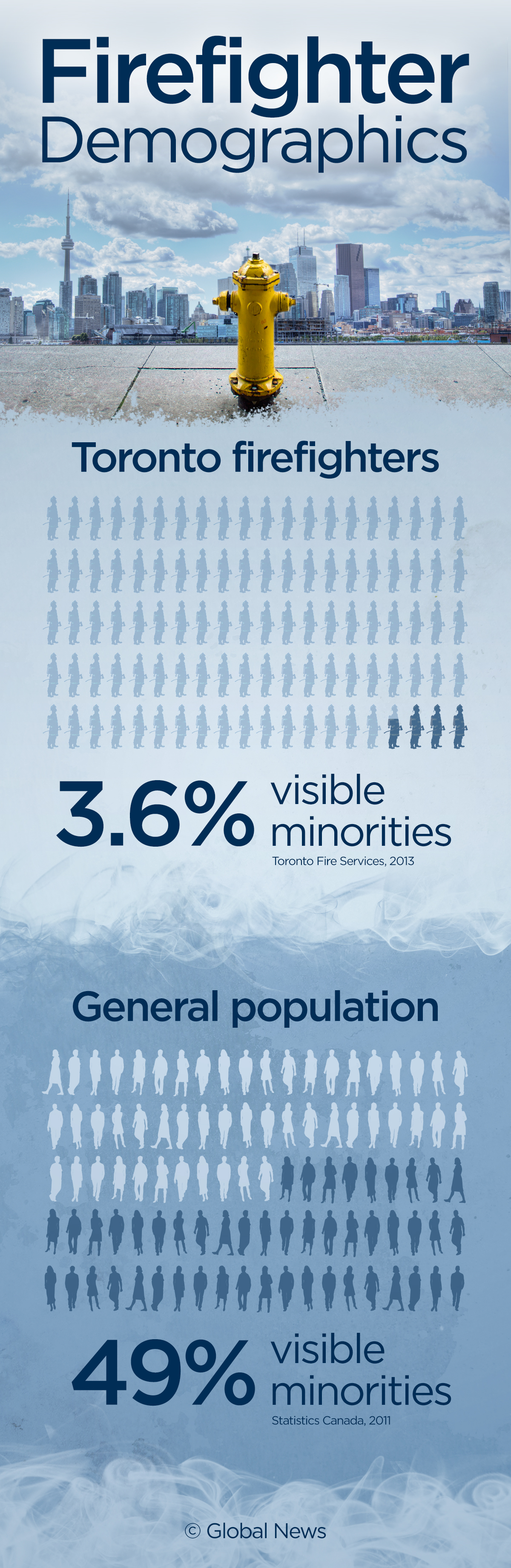

Thompson attached a motion to the budget requiring the city’s fire chief to report to council on efforts to make the fire department more diverse. (In July of 2013, 3.6 per cent of the city’s firefighters were from a racial minority.)

“I felt that there were able-bodied, qualified individuals from a variety of backgrounds in the city that wanted to be firefighters, but weren’t able to for a variety of reasons,” he explains.

So how did a city where 49% of the population say they belong to a visible minority end up with a nearly all-white fire department?

“The average Toronto firefighter has 20-plus years of service,” explains fire chief Jim Sales. “You have to look at the makeup (of the city) 20-plus years ago when the average person was hired. I’ve got people with up to 44 years. When that person was hired, what did the city look like 44 years ago? We’re not an expanding department – we hire based on retirements.”

Until recently, Thompson says, firefighting jobs “went to people who knew about the system, the internal mechanism, how it worked, when to apply, the dates to apply, what you needed to do in terms of preparing.”

“That came from (the fact that) someone’s grandfather was a firefighter, uncle was a firefighter, father was a firefighter, cousin was a firefighter, that sort of natural referral, so to speak. It just kind of worked that way, for the longest while.”

“I have no evidence to suggest that someone said ‘We don’t want those people in.”

However, Thompson’s black constituents who wanted to be firefighters had been hitting frustrating barriers.

“A young man, a very tall, strong, very athletic young black fellow, came and said: ‘I’ve been trying to get into the fire department for quite some time, and I don’t think there’s ever going to be an opportunity for me to become a firefighter, because everybody is related to someone, someone’s grandfather had been a firefighter, or brother, et cetera.”

A veteran Toronto firefighter who didn’t want to be named for fear of retaliation told a similar story.

“Back in the bad old days, it was a kind of Irish Protestant bastion,” he explains. “There was a lot of nepotism – there were sons who were hired. If your father was on, you could get on, if your uncle was on, you could get on. Back in the day, Toronto was so heavily white, that ethnic makeup just became entrenched in the department.”

In the 1990s, he remembers, open racism was quite common in the Toronto fire department: “When I first started, some of the things these people would say – you just wouldn’t believe it. Just because they’d see a white face, they’d think ‘This guy’s going to be on side.’”

“You never hear that stuff any more,” he adds. “It totally doesn’t happen.”

In January of 2013, Thompson moved a motion at Toronto city council, which ended up being carried unanimously, ordering Sales to report to council on minority recruitment.

Sales points to significant progress since then.

On Thursday, the TFS graduated what spokesperson Mike Strapko called the service’s most diverse recruit class since amalgamation in 1998 – 39 new firefighters included eight women and six members of visible minorities. A recent class was about 15 per cent women and 15 per cent visible minorities, Sales says.

At the ceremony, Ontario public safety minister Yasir Naqvi said that “the Toronto Fire Services has been a leader in creating a more accessible and inclusive fire service.”

Until recently, one serious obstacle was the one-year firefighter training course taught at community colleges, which costs would-be firefighters about $20,000.

For potential firefighters from minority groups, committing to the program meant having faith in the TFS having a fair hiring process. Often, Thompson says, they didn’t:

“They felt that if I paid the money, there wouldn’t be a chance in heaven that I would actually get in, because of what they perceived to be barriers.”

“For a lot of people who may have wanted to become firefighters, who aren’t members of the class of people who had traditionally been firefighters, what happened was that they thought that there was no way they could get in, that the system was stacked against them, and so on.”

One of Sales’ reforms was to start a fire department program offering screening to people considering the community college fire programs, and giving the best candidates conditional offers of employment before they committed to paying for a year of training.

“When we started to look at getting more females, or new Canadians, who were unaware of the Canadian system or the opportunities in the fire service in the first place, were not prepared to invest that type of money, for that length of time, without any sense of assuredness at all,” he explains.

In the process, the screening meant that people doomed to fail the medical were caught before they spent a year hopefully preparing to be firefighters, a situation Sales calls ‘appalling’.

“I’ve heard stories, and I know people, who were ultimately couldn’t make it into careers in the fire service because of medical limitations, or hearing limitations, or visual limitations, but they’ve already invested one year of their life and $20,000-plus dollars, only to find out their first time – because nobody tested them up-front, previously. I think we’re preparing some people for failure.”

Still, he worries that the college-based programs are too expensive, and says he is open to having the TFS run all its own firefighter training:

“There are people in this city that would make great career firefighters, but they have an economic challenge,” he says. “That schooling is very expensive. Trying to get funding for the uncertainties, a year of your life, the cost and the entire challenge, there are segments of society that will see it as unaffordable, or unachievable.”

So where are the recruits coming from? Outside Toronto, for the most part.

In total, under a third of Toronto fire department applicants who were offered jobs as firefighters lived in the city at the time they applied.

Since the beginning of the century, Toronto’s fire department has recruited about two firefighters from the 905 area code for every one it hired from the 416, city data shows. 28 per cent came from the 416, 57 per cent from the 905, and 15 per cent from outside south-central Ontario.

Postal codes where fire applicants lived when they were offered a job tended to have lower percentages of immigrants and visible minorities, and higher percentages of people of British Isles origin, census data shows.

That contrasts with one recruit each from the Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park high-rise neighbourhoods, which have a combined population of 56,000 people. (Two Toronto firefighters were hired from Meaford, in Grey County, a postal code with 8,000 people.)

The Toronto fire department doesn’t study where applicants come from, Sales said.

Durham Region has dense pockets of Toronto fire recruiting. Eight Toronto firefighters were hired from Courtice, 13 from the north end of Whitby, and 10 from Clarington.

North of the city, Toronto firefighters were recruited heavily from Bradford (11) and Bolton (10).

The data was released by the City of Toronto under access-to-information laws.

Since council’s motion in 2013, 68 of 251 hires have been Toronto residents, with all of the top five postal codes for recruits being in the 905 or 705 area codes: the north end of Whitby, Barrie, Schomberg/Kleinburg, rural Hamilton and Newmarket.

New York City’s fire department, similar to Toronto’s in terms of minority hiring – 7.4 per cent of the department is black or Hispanic – recently settled a civil rights lawsuit filed by the U.S. Justice Department and the Vulcan Society, an organization of black New York firefighters, for US$98 million.

“While the city’s other uniformed services have made rapid progress integrating black members into their ranks, the Fire Department has stagnated and at times retrogressed. When it comes to being a New York firefighter, blacks and other minorities face entry barriers that other applicants do not,” the judge wrote.

After the judgement, the NYFD graduated the most diverse class of new firefighters in its history, at 62 per cent visible minorities.

Comments