WATCH: In an interview with Tom Clark, Justice Minister Peter MacKay says the Conservatives most recent contentious bill will provide “consistency” for Canadians.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s most recent tough-on-crime proposal —putting more criminals behind bars for life, and eliminating parole for some —raises more than a few questions.

The intention, Harper said, is to ensure Canada’s most “dangerous,” “heinous” and violent offenders never find their way back on the streets.

But were the most dangerous men and women threatening Canadians?

1. Would this law address a known problem?

That’s difficult to say.

Murderers in Canada receive severe sentences — first-degree convictions come with a 25-year parole ineligibility period, second-degree convictions with a 10- to -25 year ineligibility period.

This regime came in 1976, after Canada abolished capital punishment, as a means to ensure murderers still paid a high price for their crimes.

The timing, however, means the first murderers released after 25 years would have hit the streets in 2001, leaving only 13 years to mine for data.

READ MORE: ‘Lifers’ in Canada’s prisons, by the numbers

So how many violent offenders released on parole after 25 years in prison reoffend?

The numbers aren’t really out there, said Isabel Grant, a professor at the Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia.

WATCH: In what looked like an election campaign stop, Stephen Harper outlined plans to keep some convicts in prison for 35 years without chance of parole.

“We don’t have any recent data on the number of paroled murderers who kill again,” she said in an interview. “We do know that violent recidivism is lower for murderers than for other violent offenders.”

Convicted murderers already receive mandatory life sentences; without being granted parole, they will spend the rest of their living days behind bars. The chances of inmates like Paul Bernardo and Russell Williams ever becoming free are slim.

Clifford Olson, for example, was incarcerated from 1981 until he died in September 2011. His numerous parole applications were all refused.

2. Is this new proposal really “life without parole?”

Yes and no.

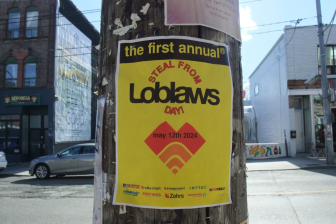

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

The bill, as the prime minister described it (the full bill will not be public until next week), does not provide for parole, per se. But there is a provision he referred to as “exceptional release.”

That would afford a murderer who, denied the usual chance for parole after a decade or quarter century, thought he deserved to get out, the opportunity to make his plea to the public safety minister.

READ MORE: Harper’s ‘life without parole’ initiative a political move, say critics

So rather than an inmate’s potential release, conditional or otherwise, going to a public and independent tribunal or to a judge and jury (as was the case before the Conservatives eliminated the faint-hope clause), the inmate’s case will go before a closed-door partisan committee.

Harper described this mechanism as a means of getting ahead of any potential constitutional challenges, but it’s caused concern for some observers.

“It’s highly problematic,” Grant said. “The reason we give these decisions to courts or parole boards is because they are independent and impartial, and are not trying to get re-elected.”

Does any politician want to be seen as being sympathetic to a murderer or sexual predator?

3. Are inmates on parole dangerous?

This goes back to the first question —there isn’t a complete picture of the post-death penalty regime and paroled inmates.

But not all prisoners are granted parole, and those who are live with strict conditions for the rest of their lives.

What could be perhaps more worrisome than former convicts walking the streets is what will happen in the country’s already overcrowded prisons.

If passed, Harper’s life-without-parole legislation could create risk in penitentiaries for guards and other prisoners, Grant said.

“People who have no chance of getting out have nothing to lose,” she said.

In other words, what incentive does an inmate have for good behaviour, knowing there is all but zero chance of release? It’s possible the criminals at which this legislation is aimed will be primarily kept in segregation, though the negative psychological effects of that form of imprisonment are well documented.

4. How much of a burden will this place on taxpayers?

The cost of keeping an inmate imprisoned has been on the rise for years.

The most recent figures from a Corrections and Conditional Release Statistical Overview analysis published on public safety’s website indicate it cost taxpayers close to $118,000 per prisoner in 2011-12 —up from close to $114,000 the year prior.

This places a huge burden on the public, Grant said, acknowledging the proposed legislation may not affect all that many people.

Comments