On January 14 2013, Canada Border Service Agency officials showed up at a detention hearing for a dead man.

Shawn Dwight Cole, a Jamaican national with a lengthy criminal record who’d been held in the Toronto East Detention Centre for 106 days awaiting deportation, died on Boxing Day, 2012. Ontario’s corrections ministry records attribute his death to “natural causes.” He had a history of seizures.

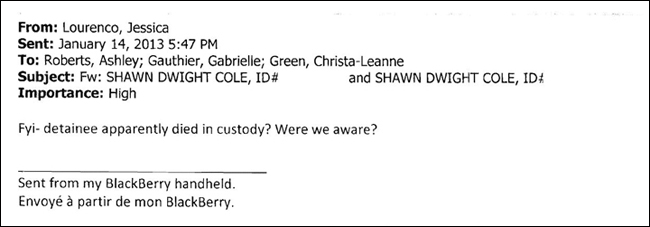

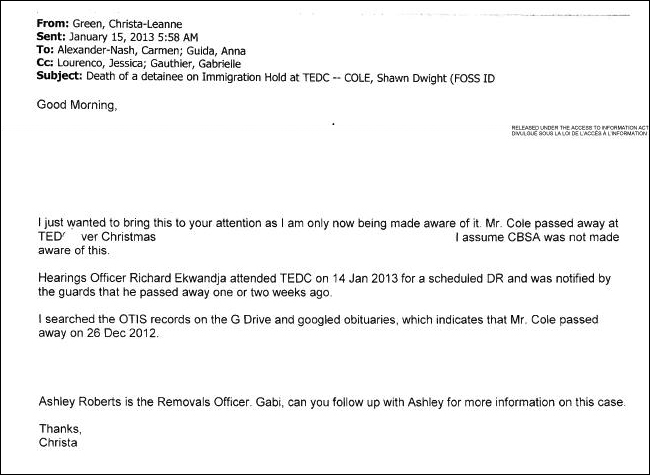

But when he died no one thought to tell the the CBSA, on whose behalf the provincial jail had been incarcerating him.

And no one told the Jamaican government until 87 days after Cole’s death, in apparent contravention of a treaty requiring Canada to inform other countries of their citizen’s deaths “without delay.”

Cole’s death also came as a surprise to the immigration consultant hired to represent him.

“I was stunned; I was shocked,” says Calvert Lewin, who had gone to the January 14 hearing to make a case for releasing Cole on bail, and was waiting with Immigration and Refugee Board officials for the hearing to begin.

“We sat down in a room waiting for him to come down, only to be told by a guard ‘He is gone; he is passed.’ The immigration officials didn’t know.”

Cole had lived in Canada since he was 15. He arrived on Christmas Day, 1992, sponsored by his mother, along with his siblings, but never became a citizen, living in Canada as a permanent resident. He did rack up dozens of criminal convictions over the following two decades, according to Immigration and Refugee Board documents, some involving guns or crack cocaine. At one point, he escaped from jail by impersonating another inmate with the same last name who was supposed to be released.

(Cole turned himself in days later; a body search found marijuana in a body cavity.)

At the same time, repeated seizures had Cole in and out of hospitals for years. He relied on this medical condition in 2010 when he asked to stay in Canada on humanitarian and compassionate grounds being ordered deported. But he had no documentation of his hospitalizations and his claim was rejected.

Get daily National news

“I have no reason to doubt that (Cole) has some form of health issue,” adjudicator Sandy Morris wrote in her decision, “(but) there is simply no medical evidence on which I can rely.”

Cole continued to resist efforts to return him to Jamaica, records of a November 2012 detention review hearing show. And in September 2012 the CBSA, still trying to deport him, decided he was a flight risk, detained him and sent him to the Scarborough jail where, less than four months later, he died.

Three weeks later, CBSA hearings officer Richard Ekwandja showed up at the jail for Cole’s 30-day detention review only to be told by guards that he had died “one or two weeks ago,” e-mails released under access-to-information laws show.

Ekwandja did not respond to an interview request.

CBSA officials confirmed Cole’s death on Google, where they found his online funeral announcement.

The jail should have told the CBSA about Cole’s death sooner but lost track due to holiday vacations, said correctional ministry spokesperson Brent Ross.

“Due to the timing of the death coinciding with the Christmas holidays, the staff who were responsible for notification to the CBSA were not in the institution and the CBSA was not immediately notified,” he wrote in an e-mail.

“The Ministry has reinforced the importance of prompt notification to ensure that this situation does not reoccur.”

Even so, the CBSA shouldn’t have lost track of a detainee to the point of not knowing whether he was dead or alive, said Reg Williams, who headed the agency’s Toronto enforcement office until 2012.

“There may indeed have been a breakdown in communication between the province and CBSA,” Williams wrote in an e-mail.

“Even then, Mr. Cole was CBSA’s detainee and therefore CBSA holds accountability. It is truly mind-boggling that such a thing could ever happen.”

Lloyd Wilks, Jamaica’s consul in Toronto, told Global News the CBSA didn’t tell Jamaican consular officials about Cole’s death until March 21. An international treaty Canada has signed requires foreign diplomats to be told of their citizens’ deaths “without delay”.

In heavily censored e-mails between the CBSA and the Jamaican consulate in Toronto in May 2013, border services official Brian Phillips struck a conciliatory note.

“My apologies for the delay in responding,” CBSA officer Brian Philips wrote in an e-mail to the consulate. “We greatly appreciate your understanding in this case.”

CBSA spokesperson Line Guibert-Wolff would not comment on this apparent delay, other than to say the CBSA “has updated its processes to ensure that in the unfortunate occurrence of a death of a foreign national in the costudy of the CBSA, the CBSA immediately informs the relevant authorities, including next of kin, and consular officials as required.”

Cole’s sister did not respond to a request for comment.

But Williams argues that kind of delay may have hurt Canada’s relationship with Jamaica, whose cooperation Canada needs when dealing with deportees.

“There is absolutely no excuse for such a lengthy delay in notifying the Jamaican consulate regarding Mr. Cole’s death,” he said. “There was a serious lapse.”

In 2013 Canada’s deportations to Jamaica hit a ten-year low – 229, down from 335 the previous year – data released under access-to-information laws show.

Canada, Britain and the United States have deported nearly 50,000 people to Jamaica since the mid-1990s, leading to resentment on the Jamaican end. Deportees have been blamed, fairly or unfairly, for a rise in crime in Jamaica.

An inquest into Cole’s death begins on March 23, and is expected to last for nine days.

Comments