TORONTO – Remember those bumps in the night?

It’s been a year since mysterious booms echoed across parts of Ontario and Quebec, jolting many of us out of our beds or chairs. It was just days after an ice storm swept across eastern Canada, from Windsor, Ontario, to the Maritimes.

And they’re back.

https://twitter.com/khibma/status/553057601257504769

In order to feel a frost quake, or cryoseism, the ground needs to be saturated with water, specifically the soil layer at the surface. Then a rapid freezing must occur. This allows the ice to expand. When that happens, it cracks rock which can feel and sound like a large boom that can shake a home.

Get breaking National news

Allison Bent, a seismologist with Natural Resources Canada said, “We run into those every year, but not the same number as 2014.”

“I think it was just the unusual weather last year. That it was colder than normal,” Bent said. “Particularly when it gets cold quickly, there’s a sudden change in temperature more than a gradual drop. That cracking sound can feel and sound like an earthquake.”

Usually the reports are very localized. So you might get one person or two reporting the booms, Bent said. However, last year, hundreds if not thousands reported them. The reason, she said, may be because it occurred in a large urban area. There is the chance, as well, that not every person did indeed experience a frost quake.

READ MORE: Southern Ontario brewery has fun with frost quakes

The challenge is confirming that the boom was caused by a frost quake and not something else. During last year’s outbreak of frost quake reports, Earthquakes Canada collected reports from varying parts of the country, including parts of Ontario, Quebec and even Calgary.

David Eaton, a seismologist and professor of geophysics at the University of Calgary, studied the Calgary frost quake in depth and helped with the gathering of reports.

“It’s a natural phenomenon. It affects people’s lives. And this provides an opportunity to study the physics of it.”

Sometimes a frost quake will produce a visible crack along the ground. And at a Calgary school, a new crack was found, which could be the source of the event.

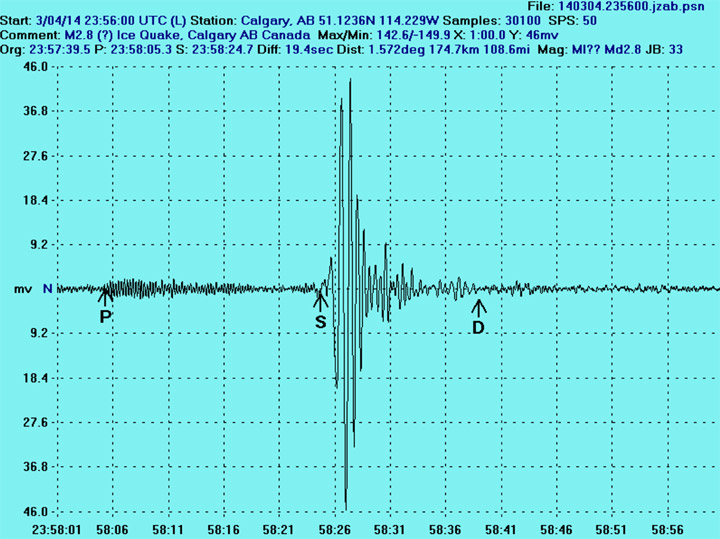

Eaton and Earthquakes Canada advertised a website where people could report the event. One person, with his own seismograph, recorded the event.

So how is it that frost quakes, which are normally localized, can be felt by hundreds of people?

“They’re very localized compared to earthquakes,” Eaton said. “The intensity of ground shaking diminishes rapidly with distance.”

After studying the Calgary event, Eaton and his colleagues found that it was stretched out. “If you were along that axis, you heard and felt it. If you weren’t, you didn’t.”

“That is consistent with it being a very, very shallow event,” Eaton said. And that supports the frost quake theory.

Eaton said it’s hard to determine whether or not we will see increased reports of this. He notes that a study on the phenomenon in New England noted that reports of frost quakes are episodic, with years with increased reports, and years without.

“That, to me, sounds like some underlying cause,” he said.

But in the meantime, you don’t have to be afraid of those booms in the night: It’s just the Earth doing its thing.

Comments