WATCH ABOVE: Canadian Television actress Lucy Decoutere speaks to Global’s Laura Brown about allegations that the former CBC radio host of Q was physically violent with her.

TORONTO – If allegations that radio host Jian Ghomeshi has been assaulting women for years are true, and those who run in Canadian entertainment circles knew or at least suspected it, why didn’t anyone say anything? And why no police reports?

These are the questions swirling around the scandal that saw Ghomeshi fired from the CBC Sunday, before posting what the Toronto Star called an “extraordinary statement” on Facebook on Oct. 26 saying he was dismissed for his “consensual” sexual behaviour.

Ghomeshi further defended himself on Facebook writing:

“I was fired from the company where I’ve been working for almost 14 years – stripped from my show, barred from the building and separated from my colleagues. I was given the choice to walk away quietly and to publicly suggest that this was my decision. But I am not going to do that. Because that would be untrue. Because I’ve been fired. And because I’ve done nothing wrong…I’ve been fired from the CBC because of the risk of my private sex life being made public as a result of a campaign of false allegations pursued by a jilted ex girlfriend and a freelance writer.”

FULL TEXT: Jian Ghomeshi’s Facebook post on why he believes CBC fired him

Since then, Canadian actress Lucy DeCoutere, author and lawyer Reva Seth and seven other anonymous women have come forward and alleged they were abused during sexual encounters with the former host of “Q.” After DeCoutere went public, Ghomeshi issued a second Facebook post saying he intends “to meet these allegations directly” Thursday morning.

Global News has reached out for comment from Ghomeshi numerous times, with no response.

WATCH: PR firm Navigator no longer representing Jian Ghomeshi

“At a certain point we started kissing…he did take me by the throat and press me against the wall and choke me. And he did slap me across the face a couple of times,” DeCoutere told CBC Radio. “He just pushed me against the wall and choked me for a little bit. I didn’t black out; I wasn’t close to blacking out. But I couldn’t breathe.”

READ MORE: Jian Ghomeshi, ‘Big Ears Teddy’ and allegations of sexual violence

The interviewer asked if DeCoutere reported the incident to the police.

“Well no, what could I possibly report? I didn’t go see the police because a) it’s his say versus my say, and also, again, the whole thing was a little confusing and I was—I put myself in that position where I was in his place, a person whom I didn’t know very well. So I know enough to know that there would be so many holes in my story they’d just be like: ‘We got nothing for you, honey,’ you know?”

Get weekly health news

It’s a sentiment that those who work in sexual assault law or services to help stop violence against women say they easily understand.

“There’s good reason for women to question whether they should report—women usually do it, if they do, to protect other women … acting in the public interest at huge personal cost,” said Elizabeth Sheehy, vice-dean of research and professor at the University of Ottawa who specializes in sexual assault law.

Sheehy provided a long list of what could be expected when reporting sexual assault to police:

- Police interviews—may be several, by several officers;

- Police make a decision whether the report is “founded” or unfounded”—they may decide they don’t believe the woman;

- They may even say they believe her but there’s no point going ahead because unlikely to be successful;

- Some women who persist/insist may be threatened with charges of mischief by police; There’s not a lot women can do if police failed to found or investigate;

- Police may undertake further investigative steps like interviewing the alleged perpetrator;

- Women sometimes ask for the rape kit results and police are not obliged to tell them what they revealed or to use it or to rush results;

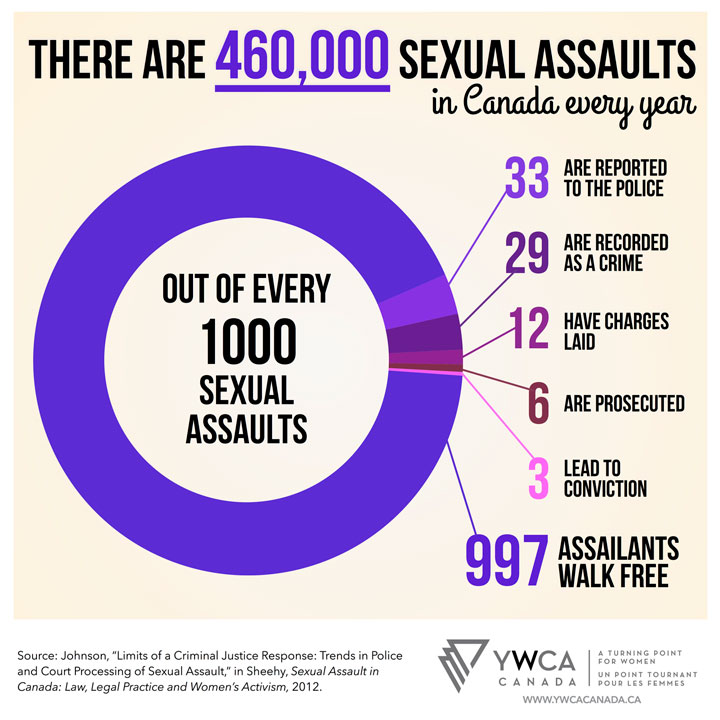

- Police unfound rape at the highest level for any crime that [Sheehy] knows of—in some jurisdictions data show unfounding at between 30% (Ottawa) to 50% (parts of BC);

- Even if the case makes it through police, they overwhelmingly charge at lowest level Tier 1, even when there are aggravating facts that should result in higher levels—i.e. weapon, bodily harm, multiple men;

- Crowns also drop charges or plead them away;

- Women experience huge trauma through cross-exam and disclosure of their records, past sexual history;

- Convictions are rare.

“One sexual assault worker here in Ottawa has been accompanying women for almost 25 years and has never ever seen a conviction,” she wrote in an email to Global News.

The burden of proof on the prosecution is a significant barrier to women coming forward with reports of assault, said Western University professor Nadine Wathen, who researches violence against women and children. Wathen pointed to a recent commentary that included examples of cross-examination questions a complainant might face at trial.

“The defence is allowed to bring in everything – so you had too many drinks five years ago in a totally unrelated situation, all of a sudden you’re being asked about your alcohol use and abuse.”

As potential bystanders, or those who’ve heard rumours or descriptive accounts, Wathen thinks people are leery to speak openly about it.

“I think we are still living in a society where violence against women generally including sexual violence is seen as a private matter,” she said.

WATCH: Why don’t victims of sexual assault report the crime? Mark Carcasole reports.

READ MORE: Ghomeshi fallout–Police chief urges sexual assault victims to come forward

A petition called “Gesture of Love and Support” for the women coming forward in the Ghomeshi case—created by a group of people from the Canadian music scene—will be helpful against the backlash on the Internet, said Wathen.

- If you want to talk about an assault or get information about potential services, you can call the Assaulted women’s helpline, available 24/7: 1.866.863.0511 in Ontario

- Toronto’s Schlifer Clinic during the day: 416-323-9149

- Fem’aide for francophones: 1-877-336-2433

- For a list of community resources throughout Ontario and Canada, try Western University’s learningtoendabuse.ca, including a section specific to neighbours, friends and families

- The YWCA Safety Siren app also provides GPS information to show you the closest health and crisis resource centre to you

Wathen said one way people cope with traumatic events is to try to minimize what happened to allow the victim to move forward in life; another reason they may not report the incident.

“That might be why there is sometimes a lag between an assault occurring and when women might come forward, but that’s used against them,” she added.

But one advocate says the reasons for lack of reporting are more broad: the way “rape culture” operates is that “we make it invisible.”

The Schlifer Clinic’s executive director Amanda Dale said there’s a tendency in society to accept inappropriate male behaviour both institutionally and socially; Dale said the more power the person has, the more invisible it is, and the more done to protect the perpetrator.

“Family members will do this: ‘Uncle so-and –so, don’t worry about him. He’s just like that. He doesn’t mean anything by it…it’s only when he drinks,’” she said.

“You can find any internal mythologies that groups will create for themselves to make the world a nicer place than it actually is. That’s what happens in what we call rape culture.”

When asked why she stayed with Ghomeshi after he allegedly attacked her, DeCoutere said she “didn’t really know how to react and I felt like if I left it would be impolite.”

“We have to drill down into how we prepare young women for their sexuality,” said Dale. “Why do we value politeness and nice girl behaviour above safety?”

Dale suggests most women believe a potential attack will happen in the street, but it’s actually behind closed doors where violence occurs. She suggests trusting instincts, telling a friend where you’re going if it’s with someone you don’t know well, and/or scheduling a time when your friend will call to make sure everything is okay.

But how you react in the moment of a surprise attack varies: Dale said sometimes it’s best to submit because it’s the “lesser danger”; sometimes it’s possible to run; if you have access you can use a loud noise like a whistle or an app created by the YWCA that sets off a siren noise.

When it comes to next steps, she said everyone is different. Friends should engage in “active listening” without judgment or pushing advice. Dale cautions to never assume you know the best thing for the victim, but suggests connecting with a group as a positive next step.

“Finding that group—whether it’s actually literally the people who’ve been assaulted by the same assailant—or whether just group of women who’ve had similar experiences, is a very powerful reversal of that isolation and stigmatization.”

Comments