WATCH ABOVE: A preview for 16×9’s “Dead or Alive.”

It was nearly 28 years ago when fisherman Stefan Zahorujko disappeared in the waters of Sasamat Lake in Port Moody, B.C. All that rescue workers found was an overturned boat and some fishing gear. No body.

A quarter century later, a hiking boot washed ashore with a foot inside. A coroner determined that the foot had been separated from the body through natural processes. But how to put a name to the human remains?

What made the question even more compelling was the fact that this was only one of nine severed feet found in B.C. waters between 2007 and 2012—all of them encased in shoes or boots. The job of solving the mystery landed on the desk of Bill Inkster, manager of the Identification Disaster Response Unit (IDRU) of the B.C. Coroner Service.

“You’ve got a shoe, you’ve got some bones in the shoe, and that’s it,” Inkster told 16×9. “We have very little idea of what the person looked like, or even if it’s male or female.”

But what Inkster did have was the technology and the science of DNA matching to put a name to all but one of the nine remains, and to notify the families. “A combination of suicides and accidents,” Inkster said, among them the drowning victim, Stefan Zahorujko. The reaction from families when he closed the missing persons cases, Inkster said, was heart-warming.

“It’s a wonderful thing. The families . . . are always very appreciative that we never gave up, that we keep making these efforts to identify human remains.”

Get breaking National news

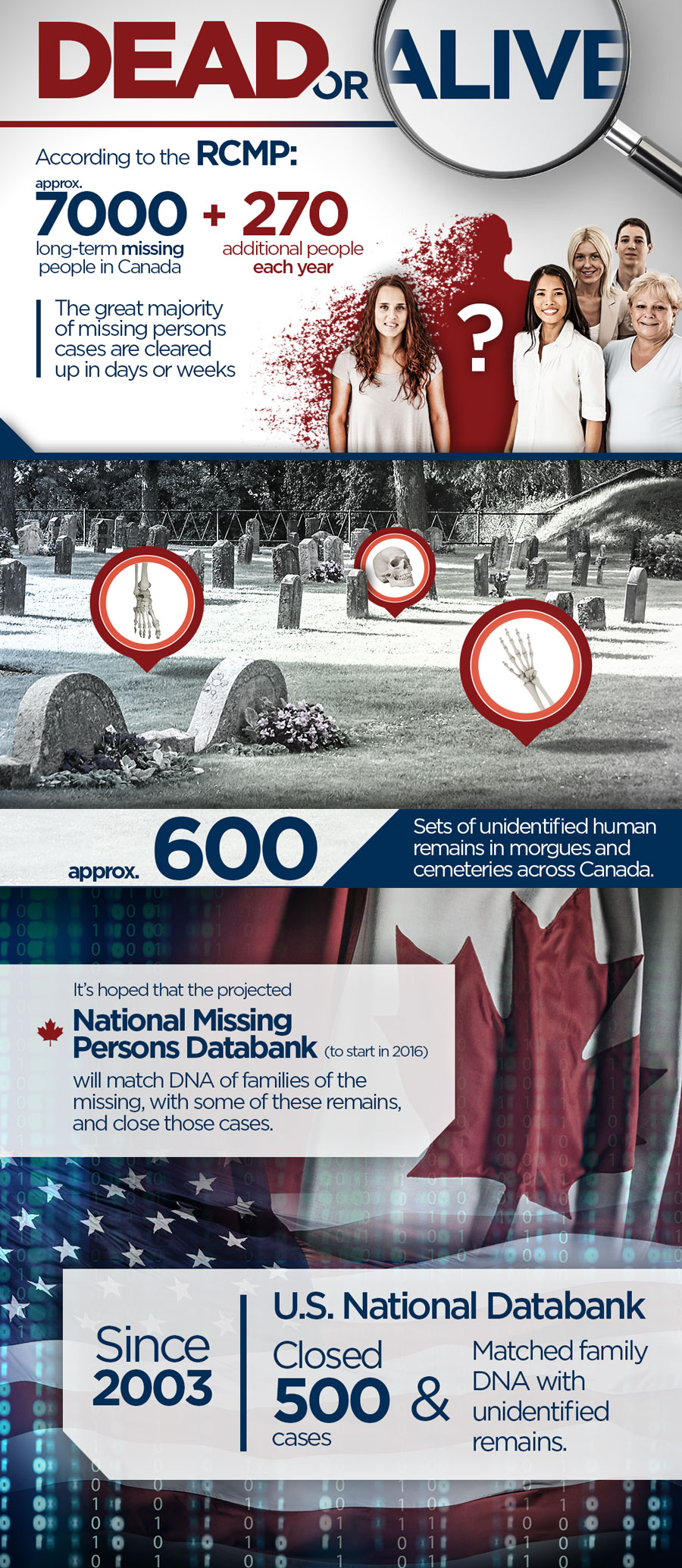

IRDU is the ideal model for a national DNA database of missing people that Ottawa hopes to roll out beginning in 2016, a database that could be instrumental in solving dozens, even hundreds, of missing persons cases. A key component would be the cross-referencing of the DNA of an estimated 600 unidentified remains across Canada, with that of families whose loved ones have gone missing for years, even decades. There may be as many as 7000 of these families in Canada.

In the United States, this technology has already helped close more than 500 missing persons cases in the past decade.

The law setting up the new Canadian database is called Lindsey’s Law, after Lindsey Nicholls, a B.C. girl who went missing in 1993. Her mother, Judy Peterson, led a tireless campaign to have Ottawa recognize the need to establish some kind of high-tech lost-and-found agency for the missing.

Peterson is proud of the fact that she persisted through the administration of seven Public Safety Ministers to achieve her goal—an acknowledgement by government that unresolved missing persons are what Peterson calls “a disaster that happens over time.”

All the details of the new legislation haven’t been worked out yet, but potentially, investigators would be able to scour tens of thousands of files in existing police crime scene indexes—a rich database of DNA information—in their search for the missing. Currently, the law forbids such searches.

WATCH BELOW: An extended interview with Amanda Boyle. Amanda’s brother and five friends disappeared 19 years ago. She believes police should have made efforts long ago to use DNA to help close the case of “The lost boys of Pickering”

Both Judy Peterson and Bill Inkster are confident that a national DNA database will help fill a deep emotional need among the families of the missing.

“I don’t want you to think that I think that once the DNA databank gets turned on we’re going to find Lindsey,” says Peterson. “But what I want is the comfort of knowing that if she’s found next week or next year, after I am dead, that somebody would know who she is.”

16×9’s “Dead or Alive” airs this Saturday at 7pm.

Comments