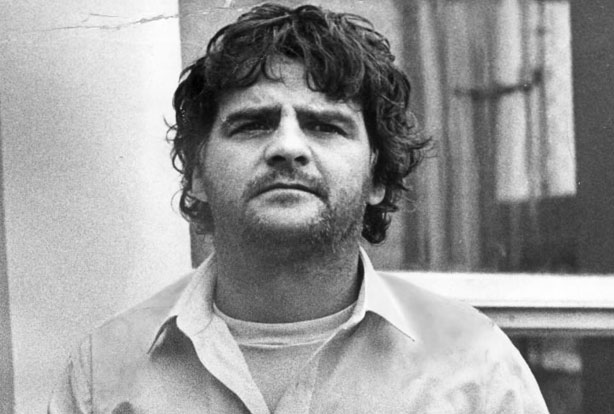

VANCOUVER – Serial child killer Clifford Olson, whose sadistically evil behaviour continued long after he pleaded guilty to murdering 11 children in 1982, is dead.

A spokesman for Public Safety Minister Vic Toews confirmed the death Friday.

Olson, the 71-year-old whose name has been repeatedly invoked over the decades by those who would bring back the death penalty in Canada, died of terminal cancer.

“These are tears of happiness, because justice is done for the children,” said Trudy Court, sister of one of Olson’s victims.

“Our justice system couldn’t do it for them. But life has. He’s gone now.”

Parents of Olson’s victims said last week they had been told by corrections officials that Olson’s cancer had metastasized and that he would not live out the month.

Sharon Rosenfeldt, whose son Daryn was one of Olson’s early victims, said the news left her relieved and confused.

“I’ve worn the Olson name for 30 years and I’ve worn it like a coat or a necklace. It’s always been there, you know?” she said in an interview after making the cancer diagnosis public.

“Will it be over? I guess I just have to wait and see.”

Olson’s megalomania, from his taunts of his victims’ families to video recordings describing his crimes from prison, has distinguished him as Canada’s most-hated criminal.

Get breaking National news

At least one of his victim’s families has said Olson mailed them a letter describing how their son died.

The self-described “Beast of B.C.” had been serving a life sentence at a maximum-security prison. He was handed 11 concurrent life terms in 1982 after pleading guilty to the murders, which occurred in and around the Vancouver area in 1981.

The admission followed a deal that paid Olson $100,000 to lead police to the remains of his young victims. The case – especially the blood-money payoff – sparked a storm of controversy that engulfed senior B.C. justice authorities.

Because the trial was aborted, much of the evidence surrounding the murders and the police investigation was never disclosed.

“Mr. Olson presents a high risk and a psychopathic risk,” National Parole Board panel member Jacques Letendre said at Olson’s parole hearing in 2006.

“He is a sexual sadist and a narcissist. If released, he will kill again.”

After her son’s death, Rosenfeldt and her husband Gary, who has since passed away, started the charity group Victims of Violence.

Rosenfeldt said she and her husband were appalled to learn after their son’s death that Olson had more than 90 previous convictions by the time he was arrested for killing the B.C. children.

She said there were numerous other charges of rape and abduction involving children, but some of them never made it to trial.

Olson’s victims, killed over an eight-month period between Nov. 17, 1980 and July 30, 1981, were boys and girls between the ages of nine and 17.

They didn’t fit the profile of troubled youth who may have run away from home. They disappeared without a trace, gripping Vancouver and its suburbs in terror. Police were under tremendous pressure to solve the disappearances.

Olson had been a suspect for weeks. He was arrested Aug. 12, 1981, on Vancouver Island after a surveillance team spotted him picking up two young hitchhikers.

Rosenfeldt said she spent about six years after Olson’s conviction mired in anger and bitterness.

But she and her husband eventually became the family most willing to respond in the media to the often bizarre developments in Olson’s case, despite the pain of having to discuss once again the ordeal.

“I obviously felt very, very deep resentment and anger towards Clifford Olson,” Rosenfeldt said in September.

“But I reached a point where, you know what, yes he could take my son’s life. But I’ll be damned if he’s going to take mine. And that’s what was starting to happen to me.

Comments