TORONTO – He was a toddler living in a small village in southeastern Guinea. Last December, he fell ill, died, but not before passing Ebola to his mother, sister and grandmother, scientists allege.

Epidemiologists who are tracing the outbreak in West Africa suspect the toddler is “patient zero” in the world’s longest and largest Ebola epidemic in history.

The boy lived in Guéckédou province, a remote village in Guinea. It may be isolated, but it acts as an intersection for the three nations hit by the outbreak – Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. For four days, the toddler was suffering from a severe fever, diarrhea and vomiting, according to the New York Times.

He died on Dec. 6. But a week later, his mother passed away, while his sister got sick on Christmas Day and died before the New Year, reports say. They were all battling the initial symptoms – which are very similar to other illnesses – so Ebola wasn’t on their radar at the time.

READ MORE: Why health officials say the Ebola epidemic won’t spread into Canada

The New York Times said that it was at the grandmother’s funeral that two mourners took the virus home to their towns, infecting relatives and neighbours.

By March, health officials clued in on the outbreak, but by then, the deadly virus was in eight communities in Guinea while cases were reported in Liberia and Sierra Leone, the Daily Mail reported.

On March 10, public health officials in Guéckédou alerted the Ministry of Health in Guinea. Two days later, Médecins sans Frontières reported clusters of a “mysterious disease” that was killing locals, according to a preliminary report published April in the New England Journal of Medicine.

(Image courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine)

Tracing an outbreak back to its origins is key in understanding what happened and preventing it from happening again, Canadian microbiologist and author Jason Tetro explained.

“Going back and finding the source is giving epidemiologists and public health officers an opportunity to find the virus before the virus finds us,” he told Global News.

In retracing their steps, health officials learn about cracks in their safety measures and how those gaps can be filled in. Figuring out how clusters of H1N1 – which started in swine in Mexico – and H7N9 – which started in birds in China – emerged in recent years have created new protocol in monitoring animals, for example.

Time is critical too, according to Dr. Joel Kettner, the medical director of the International Centre for Infectious Diseases. He was Manitoba’s chief medical officer of health from 1999 to 2012.

“The earlier this can be done, the more likely it is that an outbreak can be controlled sooner, limiting the morbidity (number of cases) and mortality,” he told Global News.

“Determining the first human being infected can help epidemiologists understand how the disease was first transmitted to a human host,” he said.

Now that the outbreak is a few months in already, Kettner isn’t sure that identifying “patient zero” adds any “practical value” over efforts to identify how current cases are emerging.

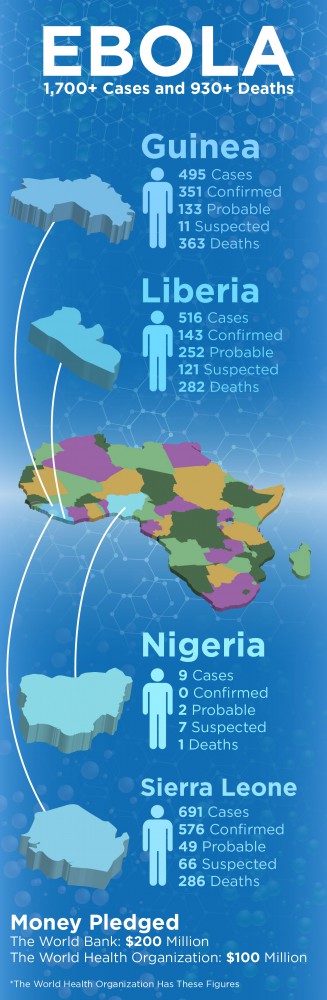

The World Health Organization (WHO) doesn’t think the outbreak will be dying down anytime soon. On Friday, it declared the epidemic an international public health emergency.

READ MORE: What the WHO’s international health emergency declaration means

“Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own,” WHO chief, Dr. Margaret Chan, said at a news conference in Geneva.

“I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible,” she said.

The declaration, which came after two days of discussion, is “a clear call for international solidarity,” but she acknowledged that many countries probably wouldn’t have any Ebola cases.

So far, the virus has killed more than 960 people and more than 1,700 people have been sickened in the current outbreak.

carmen.chai@globalnews.ca

Follow @Carmen_Chai

Comments