SPRINGFIELD, Ill. – For years, librarians at a small central Illinois library gossiped that a tattered book lying on one of its shelves justifying racism may have been in the hands of none other than Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator.

On Tuesday, state historians confirmed that theory by announcing Lincoln’s handwriting had been found inside the cover of the 700-page text, at the same time taking great pains to offer reassurance that the former president who ended slavery in the U.S. didn’t subscribe to the theories at hand, but likely read the book to better educate himself about his opponents’ line of thinking.

“Lincoln was worried that the whole idea that you could segregate one group of people based on some brand new thinking would just carry on into other realms,” Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum Curator James Cornelius Tuesday said of Lincoln. “He could foresee the whole country coming apart over the issue that different people could be barred from different things based on different qualities.”

Types of Mankind makes a case that different races were formed at different times and places and thus can’t be equals. It was seized upon by slave owners during the Civil War era as support for their way of life. The authors suggested that Africans and Native Americans were fundamentally different from Caucasians, and enslaving them was part of the natural order.

Get daily National news

Like so many other supposed Lincoln artifacts discovered in places the former president frequented, the authenticity of the inscription remained in question for years, until a new library director decided to have it inspected by experts at the state historical museum this summer.

“We didn’t know whether we should take it seriously,” Vespasian Warner Public Library Assistant Director Bobbi Perryman said.

But shortly after the 700-page book arrived at the Lincoln Library and Museum, Cornelius made a swift assessment by looking at handwriting and spacing between letters, one that was quickly backed up by other experts on staff, as well as an outside expert the museum asked to inspect the book.

“There are certain letters of the alphabet that Lincoln wrote in a way that were not common to his era,” Cornelius said, referencing Lincoln’s style of writing E’s and N’s. “A forger can typically do some of the letters in a good Lincolnian way. They’ll give themselves away on a couple of the others. This all adds up.”

Types of Mankind was published in 1854 and circulated for decades by the Vespasian Warner Library in Clinton, Illinois.

Local attorney Clifton Moore, a colleague of Lincoln’s, had donated thousands of books to the system, which formed the basis of the library’s circulating collection when it opened in the early 1900s.

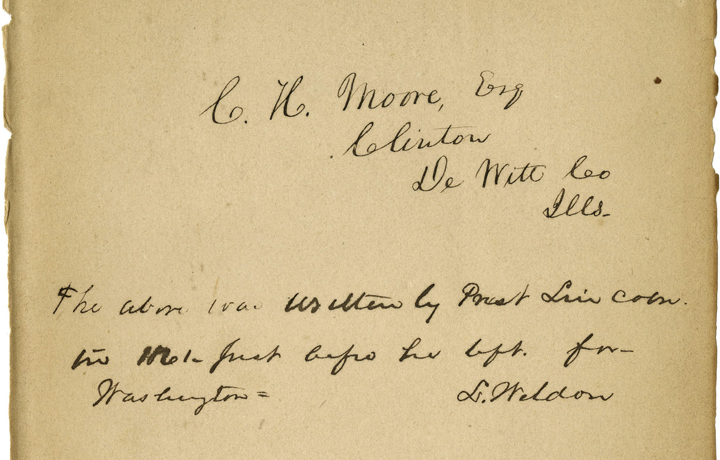

The inscription inside Types of Mankind doesn’t bear Lincoln’s signature – but a note in his handwriting on one of the first pages states that the copy rightfully belongs to Moore. Below that inscription is an attestation by another local attorney noting that Lincoln wrote inside the book in 1861, just before he left for Washington after being elected president.

Perryman said the library doesn’t know exactly when the book was retired from circulation – only that it suffered significant wear and tear from being borrowed for so many years.

Perryman said the library is currently keeping the book in its safe deposit box, with plans to restore it eventually and put it on display in a secure place.

Comments