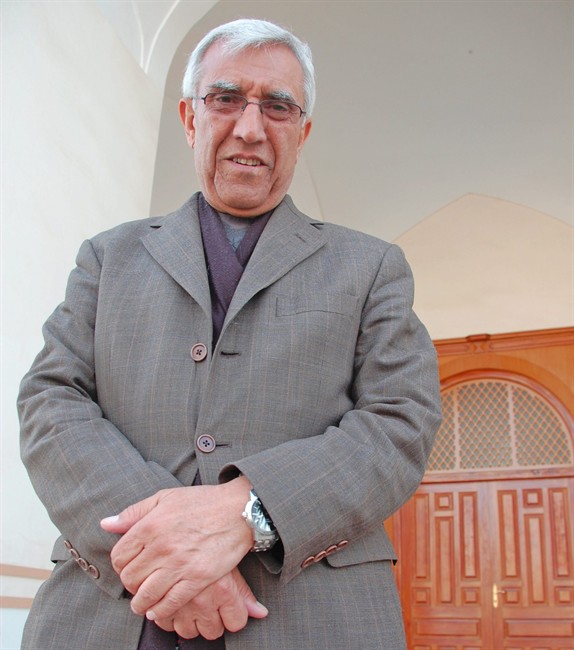

He liked to cast himself as one of the few honest men in Kandahar, a plucky troublemaker not afraid to stick a finger in the eye of authority or vested interests.

And in the end, those traits might have contributed to the brutal death of Ghulam Haider Hamidi, the outspoken mayor of Kandahar city.

He had survived previous attempts to kill him, but a suicide bomber with explosives concealed in his turban assassinated Hamidi on Wednesday.

Hamidi, 65, was the third high-ranking official in the volatile southern Afghan province to be murdered this year. The president’s half brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, and the provincial police chief, Gen. Khan Mohammad Mujahid, were killed earlier.

The Taliban claimed responsibility, saying it was revenge over a land dispute involving the demolition of 200 illegally constructed homes in the city’s vast northern slum – an act that insurgents claimed had caused the death of two children.

That alleged zoning disputes continue to be settled with bombs in Kandahar is setback for the U.S., which took full control of the province from the Canadian army a few weeks ago.

Hamidi, who spent 30 years in exile in Arlington, Va., as an accountant, said in recent interviews with The Canadian Press that he knew he was marked for death but accepted the risk as his way to give back to the city he loved.

He was appointed Kandahar mayor in 2007. “I didn’t do my job for Ahmed Wali Karzai. I did not do it for Mr. Hamid Karzai. I do my job because I owe this city,” Hamidi said last December.

“I (was) born here. I grew up here. I eat from this city. I was educated in this province and I had good times here. Now in the last times of my life, I want to spend it here, serving my city and city citizens.”

Get breaking National news

“I could go back to America, but I choose to be here,” he said. “I will fight, fight corruption (and) those corrupt people. This my city. Kandahar is my city and I will die here.”

Hamidi has a daughter and grandchildren in Toronto, and another daughter who returned to Kandahar with him in 2007 to set up a business.

Canada’s ambassador in Kabul, William Crosbie, condemned the murder as a cowardly, senseless act.

“Mayor Hamidi served the people of Kandahar with dedication and dignity,” Crosbie said in a statement. “He worked tirelessly to bring about peace and prosperity in Kandahar city and throughout the province. This is a great loss for the people of Kandahar and all of Afghanistan.”

The Taliban, eager to claim responsibility for sensational attacks, may indeed be behind the assassination _ which resembled the bombing that killed the province’s head cleric during a memorial for Ahmed Wali Karzai in mid-July.

But Hamidi had regarded shadowy, entrenched power brokers and drug lords as his biggest threat. It was their authority that he challenged most often. It was they whom he blamed for the March 2009 roadside bombing attempt on his life, an attack that took place within sight of local police.

“They put (a) bomb 60 metres from a police checkpoint. How are they coming here?” Hamidi asked.

“The municipality office is the only organization that wants to fight corruption. Now those corrupt people want to destroy the municipality office and (don’t want it) to serve the people.”

The point he repeatedly hammered home to westerners was that local warlords whom NATO relied upon benefitted from having an unstable government _ just like the Taliban.

“I am conducting jihad against these corrupt people,” he said earlier this month at his office in the provincial governor’s palace.

Hamidi seemed hard-pressed to hold it together sometimes. The murder of two deputy mayors since 2009 resulted in a panicked stampede from municipal offices as nearly half the 109 employees quit out of fear for their lives.

Undeterred, the mayor carried on and even fired some officials who worked as engineers under false credentials. He also tossed some district managers who were taking bribes.

Hamidi recently angered the establishment by ordering that shops set up near the city’s beautiful blue mosque be closed and bulldozed because they were too close to the holy site.

He wasn’t afraid to involve the president in some land disputes, where powerful squatters with no title to property would set up shop and charge outlandish rent to both the Afghan government and foreign armies.

The mayor also made waves with the departing Canadians, criticizing a $1.9 million project to erect solar streets lights in the city, many of which initially didn’t work.

When his complaints were not answered, he took the matter public, accusing Foreign Affairs of wasteful spending and the Harper government of hypocrisy for insisting that Afghans clean up corruption.

His outburst earned him a letter of rebuke from the federal government, which he displayed during an interview as almost a badge of honour.

In his parting interview with The Canadian Press, Hamidi said he often looked for ways to demonstrate that Kandahar, despite its poverty and seemingly endless violence, was just like every other city.

He donated US$50,000 of surplus municipal funds towards tsunami relief in Japan.

“I believe in the near future, we will tell our brothers: ‘Thank you very much for your help, we don’t need it any more’,” Hamidi said. “After that, we will be able to help some other countries that are poorer than us.”

Comments