Under growing pressure from the public, city officials are gearing up to debate whether the Vancouver Aquarium should begin phasing out holding cetaceans in captivity.

The hotly debated issue has prompted local petitions, protests and plenty of public comment demanding the aquarium “empty the tanks.” The movement has gained traction ever since the popularity of the documentary Blackfish flung the issue into the limelight.

In July, the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation will begin hearing from the public, the aquarium and other stakeholders in hopes of making a decision before the November civic election.

At that time, they will review a report from the aquarium outlining operations of their current captive cetaceans. Following their review, the park board has the right to ban the animals from the site or enforce a phase-out plan without a public referendum.

In addition to the public, several city officials and Dr. Jane Goodall have also publicly urged the Vancouver Aquarium to phase out the cetacean exhibits.

On Tuesday, the Vancouver Aquarium issued a response to Goodall, stating that she may have incomplete information and has never visited the facility.

For the aquarium, the timing couldn’t be worse. They are in the throes of a $100-million expansion, the first phase of which is set to be complete in time for their busy summer season.

Several countries and some U.S. states already prohibit keeping cetaceans in captivity.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Where in the world is it illegal to keep cetaceans in tanks?

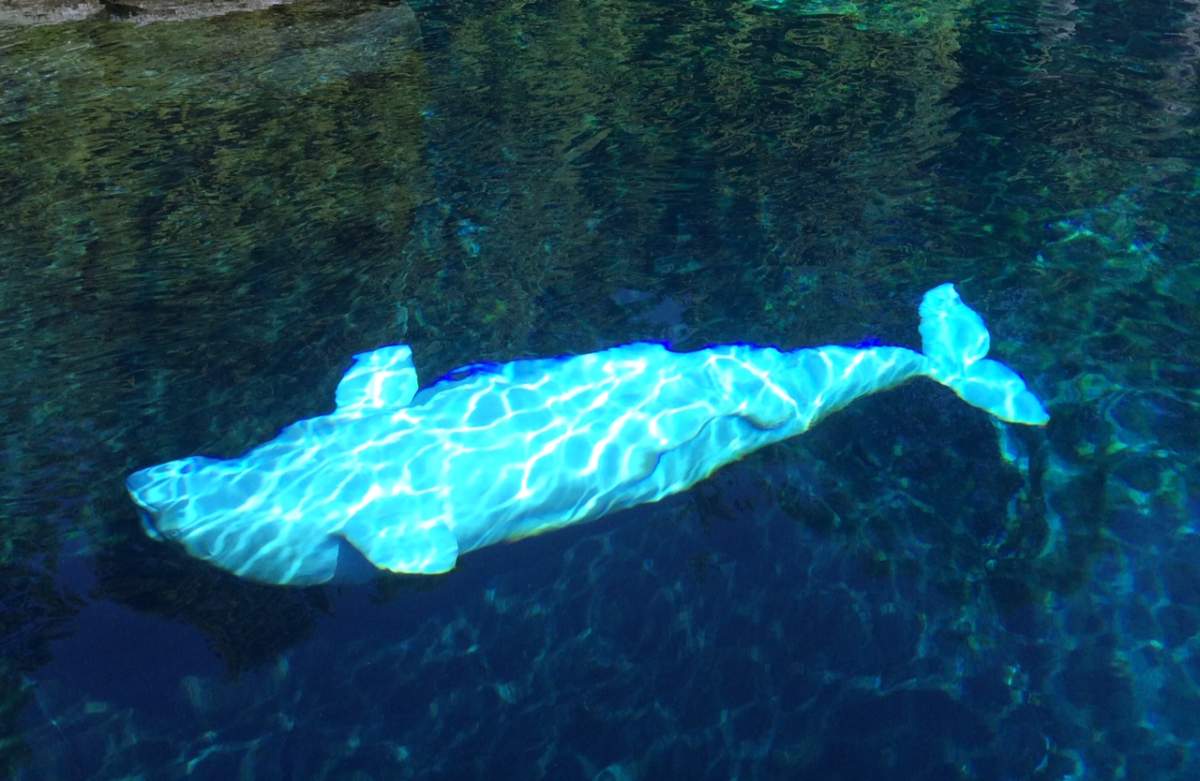

Baby beluga in the deep blue tank

The aquarium currently holds two Arctic beluga whales and two Pacific white-sided dolphins.

Beluga whale Aurora, who is around 27 years old, was captured from the wild near Churchill, Manitoba in 1990. She gave birth to the second beluga at the aquarium, Qila, in 1995. Aurora has given birth to two other calves, who haven’t survived. In fact, four out of the five belugas born at the aquarium have all died.

GALLERY: Up close with the Vancouver Aquarium’s belugas, dolphins and marine mammals

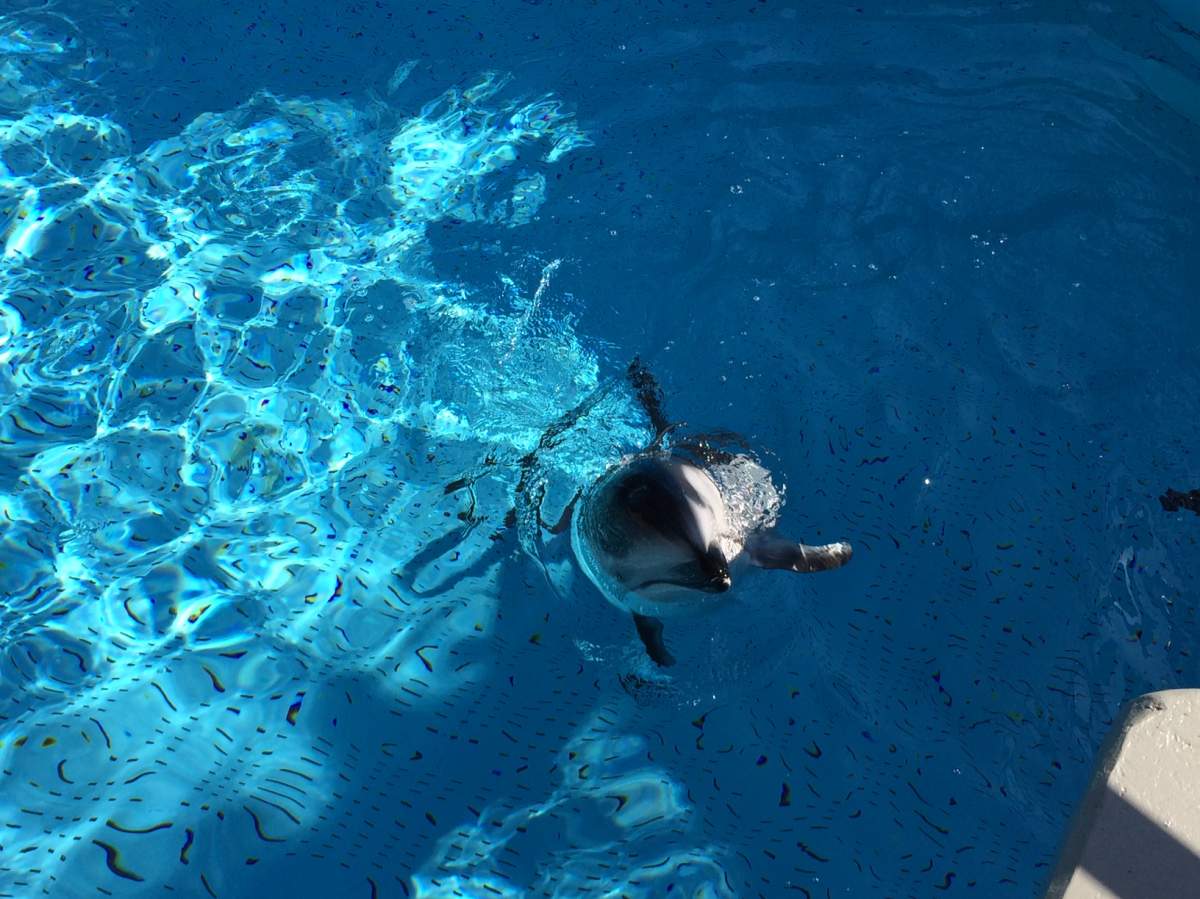

Just across the Arctic exhibit, live two Pacific white-sided dolphins, who the aquarium says were rescued after getting entangled in a Japanese fishing net in 2005.

Hana, who is around 18 years old, and Helen, who is around 24 years old, couldn’t be released back into the wild because of injuries from the entanglement and Helen has the amputated fins to prove it.

Growing support to “empty the tanks”

Get daily National news

Opponents say it’s cruel to keep cetaceans, many of which can travel hundreds of kilometres a day in the wild, kept in tanks to circle endlessly.

“It’s torture,” said Annelise Sorg, president of activist group No Whales in Captivity.

“It’s now well documented in scientific terms that it’s tortuous for whales and dolphins to be placed in tanks and forced to perform.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lxSnnmXsdY

Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson has also expressed support in phasing out the cetacean exhibits.

“My personal view is that the Vancouver Aquarium should begin to phase out the holding of whales and dolphins in captivity. I’m hopeful that the aquarium and the park board can work collaboratively and come to an agreement on how to achieve this with a dialogue and review that will be informed, thoughtful, and inclusive,” Robertson said in a statement.

At least three park board commissioners have also spoken out against having belugas and dolphins at the aquarium.

“I do believe at this time that we live in a world where we have evolved beyond having these intelligent mammals in captivity,” said park board commissioner Sarah Blyth. “The question is, what do we do now and how do we approach this?”

Aquarium says whales and dolphins are critical to research, receive “exceptional care”

The Vancouver Aquarium draws hundreds of thousands of visitors every year, many of who come specifically to get an up close look at the belugas and dolphins that call the facility home.

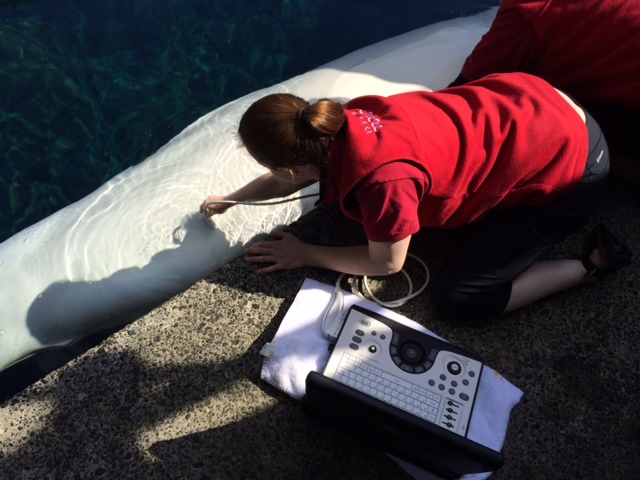

In addition to training cetaceans and maintaining their live exhibits, staff at the aquarium say they are also deeply dedicated to the conservation and preservation of marine life, mammals and the world’s oceans.

They also run a Marine Mammal Rescue Centre that has successfully rehabilitated and released animals back into the wild. Without the revenue from their cetaceans exhibits, aquarium staff worry funding for their research and rehabilitation programs could be compromised.

WATCH: Sea otter blinded by gunshot wounds makes slow recovery at Vancouver Aquarium

Aquarium staff are hoping for a long future with whales and dolphins on site.

“The animals here are extraordinarily well cared for,” said Clint Wright, senior vice president and aquarium general manager. “From all the behaviours we’re observing from these animals, they’re exhibiting normal behaviours, they love interacting with the trainers, they love going down to look at the public in the underwater viewing windows and they seem to be thriving and very content here.”

INTERACTIVE MAP: Whales and dolphins in captivity in North America

Wright, who started as an orca trainer at the aquarium 25 years ago said it’s critical to have the belugas and dolphins at the facility so they can continue researching and helping wild populations.

“Now is not the time to stop learning about these animals,” Wright said. “Having them here is vital and with the climate changes that is going to be happening in the Arctic… that’s going to be impacting wild populations of belugas… and we need a couple well cared-for animals to be able to study them.”

Wright also said the cetaceans have real relationships with the animal-loving aquarium staff, many of who spend “more time with the animals than they do their own families.” According to Wright, the animals love performing for their trainers and the public.

“Looking at these animals they seem to be really enjoying it,” he said.

What will happen to the whales if they are phased out?

If the park board decides to ban cetaceans, the fate of Aurora, Qila, Hana and Helen is uncertain.

Blyth said most people do not expect the four existing cetaceans to leave the aquarium and the decision will more likely involve having a plan for the future to phase out breeding and bringing any additional whales or dolphins to the facility.

“Do we need to send them in airplanes and all over the world? Is that necessary in the world anymore?” she said, adding that all options will be considered.

However, the aquarium doesn’t want the dolphins and belugas to be sent to another site.

“These are animals that cannot go back to the wild. They’ve lived here for a long time, so really you’re saying ‘we don’t want them here, but we’re ok having them somewhere else’… we can provide them long-term homes here. We need to think about what’s best for these particular animals and right now it’s being here at the aquarium,” Wright said.

In the past, moving whales to different aquariums hasn’t always been successful.

In 2001, the aquarium closed its orca exhibit after 37 years. The Vancouver Aquarium was the first facility in the world to capture an orca from the wild and keep it in captivity in 1964.

Its last whale, Bjossa, was shipped to SeaWorld in San Diego. It died five months later from a respiratory illness.

No Whales in Captivity believes that closing the cetacean exhibits would still be a win for their cause even if the existing animals were shipped somewhere else.

“It will create a domino effect,” Sorg said. “Our only job is to bring public awareness that it’s cruel to breed and capture cetaceans and make them perform. The only way to stop it is to close every tank.”

ONLINE POLL:

Comments